This year marks 500th anniversary of Strait of Magellan

–Commodore (Rtd.) BR Prakash

–Commodore (Rtd.) BR Prakash

This year marks the 500th anniversary of the discovery of a passage, Strait of Magellan, connecting the Atlantic Ocean with the hitherto undiscovered Pacific Ocean, which changed the world forever.

The Magellan expedition was responsible for several major discoveries. In addition to the Pacific Ocean and numerous islands, waterways and other geographic information, different zones of time, the expedition also sighted a great many new animals, including penguins and guanacos. The discrepancies between the logbook and the date when they returned to Spain subsequently led to the concept of the International Date Line. The recorded measurements of distances travelled helped contemporary scientists determine the size of the earth. They were the first to sight certain galaxies visible in the night sky, now aptly known as the Magellanic Clouds. Magellan and his crew had also unknowingly discovered “trade winds.” The name would come from the important role they would later play in transoceanic trade.

The voyage symbolises the indomitable human spirit for exploration, discovery and adventure. The technological, physical and mental challenges to be triumphed during the long voyage were staggering. Maritime navigation during the 16th century was nowhere as effortless as it is today and neither was seafaring for the weak hearted, as sailors led dangerous lives, not least because they seldom knew their exact location on the open ocean. This was the age of the sail when the tools for navigation at sea were still rudimentary – astrolabe and quadrant (the sextant yet to be invented), naval cartography was in its infancy and the world was still thought to be flat. It was enterprising sailors like Vasco da Gama, Nunez de Balboa, Ferdinand Magellan who took the risk, as they were men with fortitude, audacity and courage to brave the odds.

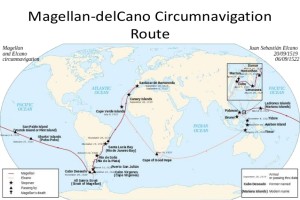

It was an epic voyage starting in 1519, led by an intrepid sailor and one of the most extraordinary explorers of the Age of Discovery, Ferdinand Magellan, who for the first time placed in the maps a new and immense ocean (Pacific), and also the Strait that connected the two big oceans – the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. This eponymous voyage led by Magellan ultimately culminated in the first circumnavigation of the globe, though he did not live to see it happen. The long and arduous voyage through some of the most treacherous and unforgiving oceans ended in Spain three years later in September 1522, with only one out of the 5 limping back to harbour with 18 of the fleet’s original crew of 270.

A little digression, at this stage, may not be out of place. There is a trivial India connect to this story. Magellan, or Fernão de Magalhães as known in Portuguese, was born in 1480 in Portugal. He had enlisted in the Portuguese fleet sent to host Francisco de Almeida as the first viceroy of Portuguese India. This may have been the period where he developed his skills as a navigator. He remained in India for eight years, living in Goa, Cochin and Quilon. It is recorded that he participated in several battles, including the battle of Cannanore in 1506 and the battle of Diu in 1509. In 1511, under the new governor Afonso de Albuquerque, Magellan participated in the conquest of Malacca and thereafter returned to Portugal in 1512. After taking leave without permission, Magellan fell out of favour with King Manuel of Portugal. He was also accused of trading illegally with the Moors in Africa and he received no further offers of employment after May 1514. In 1517, a frustrated Magellan renounced his Portuguese nationality and relocated to Spain to seek royal support for his venture of sailing West to find a new route to the spice Islands of Indonesia. King Charles I granted his support to Magellan and preparations began for the voyage.

Magellan set sail from Seville in Spain, on September 20 1519, in command of Armada de Molucca, as it was called, comprising five ships (Trinidad (his flagship), Victoria, San Antonio, Concepción, and Santiago). His crew of 270 included men from several nations- Spain, Portugal, Italy, Germany, Belgium, Greece, England and France. It turned out to be voyage with all the trappings of a “Pirates of Caribbean” movie – mutiny, war, storms, hostile native encounters, marooning, starvation, and harassment by Portuguese ships.

The fleet sailed along the West coast of Africa and reached Rio de Janeiro, South America in December 1519. The fleet hugged the coast of South America, heading steadily south—sailing only during the day and anchoring at night—searching for the fabled strait that would take them to the Spice Islands. As voyage progressed, life at sea became increasingly hard and Magellan decided to wait out the winter. The fleet established a settlement at Puerto San Julián in Patagonia (Argentina). Magellan reduced rations and tried to keep the men busy, but dissension, especially among the Spanish captains and crew, soon erupted into midnight mutiny on 02 April 1520. However, with subterfuge and some luck, Magellan quickly seized control and crushed the mutiny. Luis de Mendoza, the captain of Victoria, was killed in the fighting; Gaspar de Quesada, the captain of Concepción, was executed—their dead bodies were drawn and quartered and put on display. (Later, two other conspirators, Juan de Cartagena, the captain of San Antonio, and a priest named Padre Sánchez de la Reina, were left marooned on the coast when the fleet left.)

Having firmly quelled the uprising, Magellan sailed on in search of the elusive passage. Disaster again struck, when Santiago sent to explore the route ahead, was shipwrecked during a terrible storm. The ship’s crew-members miraculously survived and were rescued and assigned out among the remaining ships. With those disastrous events behind them, the fleet left Port San Julian five months later when fierce seasonal storms abated.

However, foul weather continued to hinder their progress. Magellan had the first break on 21 October 1520 when the fleet reached a headland, beyond which, cutting into the landmass, stretched a broad and deep waterway with strong currents. Since 21 October was the feast day of Saint Ursula and the Eleven Thousand Virgins, he named the cape in their honour as the Cape of the Eleven Thousand Virgins (today’s Vírgenes). He had finally found the sought after passage. Magellan methodically advanced into this Never Never Land. Seeing distant fires at night, indicative of human settlements, he named the area Tierra del Fuego, Land of Fire. Navigating the 350 miles, long passage turned into a nautical nightmare, owing to the high tides (up to twenty-four feet) and strong winds and currents. The voyage through the strait was treacherous and cold, and many sailors continued to mistrust their leader and grumble about the dangers of the journey ahead.

After thirty-eight days, negotiating channels, bays, and glacier-fed fjords, past huge, snow-capped mountains and coarse, evergreen shores, surviving a fierce williwaw and the rebellion of another ship, Magellan achieved part of his goal – entry into the Pacific Ocean. During the transit through the strait, San Antonio, the largest in the fleet, containing provisions, deserted the fleet and headed back to Spain. From this point on, only three of the original five ships remained in Magellan’s fleet. The three ships reached Cape Desire on 28 November 1520, and entered an ocean Magellan called pacific for its mildness. According to historical weather research, Magellan probably benefited from El Niño, which provided calm winds across the Pacific during his crossing.

After this success, Magellan thought it was a matter of a few weeks of sailing before he would reach the Spice Islands. However, no one realized that the greatest expanse of water on the planet lay ahead. Magellan’s course, first northward along the western coast of South America and then west, unluckily avoided virtually all of the ocean’s twenty-five thousand islands. This leg of the voyage was the most despairing period for the crew with no land insight day after day. The crew survived on biscuits swarming with worms and stinking of rat urine, ox hides used to cover top of main sails, sawdust, rats (sold for half ducado) and yellow putrid water during this period. 19 sailors died on Trinidad alone during the transpacific crossing. On this leg of the voyage across the Pacific, they sighted land only once (barren atolls of the Tuamotu Islands, which Magellan dubbed Islands of Disappointment) before reaching Guam in the Ladrones (“Islands of Thieves,” today’s Marianas) on 06 March 1521. The pacific crossing took all of ninety-eight days. Finally, at Gaum, they found and ate fresh food for the first time in 99 days.

Overcoming multitude of challenges during this protracted and gruelling voyage is a remarkable testament to the abilities of Magellan as a navigator and strategist and to his crews’ forbearance and skill. The expedition literally changed the world and the known knowledge of it at that time.

For nearly 400 years, the Strait of Magellan continued to be the main route for ships sailing between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The Magellan Route has been put by Portugal for inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List as it can be compared with other transboundary properties already inscribed in the such as the Chinese Section of the Silk Road and the Qhapaq Ñan Andean Road System. Despite its narrow 600 km-long passage through a clustered network of islands and fjords, it was found to be a quicker and safer route than rounding Cape Horn to the south and entering the infamously turbulent Drake Passage that separates Cape Horn and Antarctica’s South Shetland Islands. However, the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914 caused sea traffic through the Strait to decline significantly.

P.S. Many of the details of this fascinating voyage of discovery is based on two written records. The first was a journal kept by Antonio Pigafetta (died in c. 1531 (age about 40–50)), a Venetian scholar who had signed on as a supernumerary and was assigned the role of official expedition chronicler. The second was a series of interviews with the survivors made by Maximilianus (1490AD -1538 AD) of Transylvania upon their return.

*The writer retired as Commodore from Indian Navy in 2017. He is an alumni of TS Rajendra and specialised in Missile and Gunnery and also served as Surface to Air Missile Officer and Gunnery officer on a number of Indian Naval ships. He commanded INS Vidyut , INS Ganga and was the commissioning CO of INS Sardar Patel.