Photo credit: Htoo Tay Zar @tayzar44|Twitter

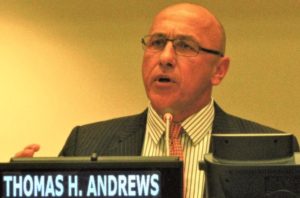

We present excerpts from a 52-page report submitted to the Human Rights Council on March 4, 2021 by the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Thomas H. Andrews. In the report Andrews details how the Myanmar military illegally overthrew the civilian government and proceeded to attack the people of Myanmar by committing the crimes of murder, assault and arbitrary detention.

People of Myanmar Exercise their Rights

The military coup d’état has united the people of Myanmar. Millions have taken to the streets throughout the country to demand democracy and human rights and an immediate end to the junta. Protesters include Buddhist monks and Muslim clergy marching side-by-side; civil servants from various sectors; doctors and nurses, workers and trade unions, bankers and educators; Karen, Chin, Shan, Kachin, and other ethnic groups; the very young and the very old. The people of Myanmar are rightly demanding the release of the State Counsellor, the President, and all political prisoners. Many are calling for a new constitution to remove the military from politics once and for all. The vast majority of the people of Myanmar are united in vehement opposition to the coup and embrace the CDM. Many ethnic-majority Burman protesters have also expressed regret over not previously recognizing the military’s atrocity crimes against ethnic minorities, specifically referencing the Rohingya.

Civil Disobedience Movement

On 2 February, the day after the coup, people throughout the country banged pots and pans—a traditional practice to ward off evil spirits—in unison at 8:00 pm to protest the military takeover. By 6 February, a well-organized, though organic and nominally leaderless, civil disobedience movement took hold. Healthcare workers, celebrities, civil servants, professors, lawyers, religious leaders, and others participated early on in the campaign. “Generation Z” (those younger than 25-years old) assumed a prominent and leading role in the movement.

Also read: The Myanmar Report – 1

The Special Rapporteur received reports that public sector workers from at least 245 districts (out of 330) representing 21 ministries had gone on strike in the first weeks of the coup. The strike spread from healthcare workers to public-sector employees across numerous ministries, including Railway, Customs, Commerce, Electricity and Energy, Transport and Communications, and Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation. Teachers, central bank employees, and other government officials joined. In the private sector, trade unions called on their members to strike and bank tellers, cooks, grocery workers, and others joined the CDM.

On 19 February, the “Anti-Military Dictatorship General Strike Committee” was formed with the goal of creating regional strike committees, supporting participants in the CDM, and sustaining and coordinating the CDM movement.2 The largest street protests since the coup—and quite possibly ever in Myanmar—occurred on 22 February (dubbed “the five 2s”), with unconfirmed estimates of “millions” of people nationwide in the streets, despite the junta’s threats of “loss of life” televised the day prior.3 The people of Myanmar have held peaceful protests in at least 247 of 330 townships throughout the country.

The CDM has brought the functions of the State to a near halt. Strikes across almost all sectors of society, including banking, have reportedly brought physical cash circulation to a “trickle” and transactions at banks have mostly ceased. Myanmar’s currency, the kyat, has depreciated, driving costs up while many employees go unpaid. Refined oil imports have stalled.

The State Administrative Council (SAC)’s Violation of Rights

The junta has responded to the people of Myanmar’s nonviolent and peaceful protests with murders, beatings, mass arbitrary detentions, intimidation (including a threat via state-run television that protesters could “suffer the loss of life”), and systematic repression of civil and political rights. Mass protests and strikes continue.

Murder

The Special Rapporteur received credible reports that as of 1 March, Myanmar security forces murdered at least 23 individuals. The Special Rapporteur stresses, however, that as this report goes to print, details of a nationwide-deadly crackdown on 3 March are emerging, with credible reports, yet to be confirmed, that at least 38 people were killed on this day alone. All of these murders since the coup are in violation of international law and many, though not all are highlighted below in the context within which the junta’s security forces conducted the murders.

Female teenager, murdered in Naypyitaw: On 8 February 2021, Min Aung Hlaing addressed the people of Myanmar on live TV for the first time since the illegal coup d’état. He stressed, “We are taking [over] State responsibility based on unavoidable reasons . . . we shall build a genuine and disciplined democratic system.” That same day, the junta invoked Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code in townships across the country, prohibiting public assemblies larger than five persons and imposing a curfew from 8pm to 4am.

On 8 February, Myanmar police deployed water cannons against protesters and fired rubber bullets directly at protesters, including in Naypyitaw.

On 9 February, tens of thousands of people took to the streets in more than 300 towns and cities throughout Myanmar. A nineteen-year-old student was among the protesters in Naypyitaw that day demanding a return to the civilian government. As police fired a water cannon into a crowd of protesters, she and her sister took cover behind a bus stop. The Special Rapporteur has viewed video that shows the victim wearing a helmet, with her back turned to the police, suddenly collapse to the ground. Her sister removed the victim’s helmet, revealing blood and what appeared to be an entry wound in the back of the victim’s head.

Her sister and others quickly transported her to Naypyitaw’s general hospital. According to the medical doctor who treated her, she was shot in the head with a live round, the injury would be fatal, and she was effectively brain dead. A doctor on the scene reported that the military attempted to transfer the victim to a military hospital in order to, in the doctor’s belief, “try to conceal evidence of this incident,” but the doctor successfully argued that the severity of her injury required she stay. The doctor is now in hiding, fearing repercussions from the junta.

In a statement, the junta denied responsibility, claiming police were only carrying anti-riot control weapons on 9 February and that the bullet in her brain was not consistent with ammunition the police use. The Special Rapporteur viewed photographs showing a member of the Myanmar police stationed in the vicinity of the victim aiming a Myanmarproduced version of an Israeli Uzi, debunking the claim that police only deployed anti-riot equipment.

Junta leader Min Aung Hlaing further dismissed her killing in a State Administrative Council meeting on 23 February. In published reports, Min Aung Hlaing appeared to blame her for her injury, saying that she “participated in the riots.” He repeated the false claim that police only used rubber bullets.

Her birthday was two days after being shot, and her family removed her from life support a week later. She died on 19 February. Thousands attended her funeral procession.

Three adult males and one teenage male, murdered in Mandalay: On 19 February, as the CDM and general strike continued to gain momentum, civil servant dockworkers at the government-run Yadanarbon Shipyard in Mandalay went on strike, preventing a ship from departing. Myanmar police intervened, attempting to force the civil servants back to work. Residents in the surrounding area soon gathered to protest the actions by police, who then attacked protesters. The Special Rapporteur viewed video showing police charging at protesters and firing on them. Reports from Mandalay on 20 February indicate Myanmar security forces fired well over 100 gunshots at protesters, including live ammunition.

A sixteen-year-old boy was among those fired upon. He worked at a local market, where vendors called him “little boy,” with the goal of earning enough money to purchase a mobile phone and motorbike. He joined in the protests on 20 February as the group reached the market where he was working. The Special Rapporteur viewed video and photos of numerous individuals sheltering from gunfire, and then moments later, the boy is seen lying on the ground with a large, fatal gunshot wound to his head. The Special Rapporteur also viewed video of the boy being transported to a makeshift triage center at a monastery where volunteer medics were simultaneously treating individuals with gaping bullet wounds. Medics quickly determined that the boy was dead and placed a red sheet over his face.

On the same day, security forces also shot a 36-year-old husband, father, and carpenter with live ammunition while he protested the security forces’ efforts to end the dockworkers’ strike. The Special Rapporteur viewed photos of the man immediately after he was shot in the abdomen. He died in an ambulance en route to a hospital.

Security forces shot a third man in the leg on 19 February in Mandalay. He died on 23 February while in junta custody. The junta insists he died of COVID-19, though the Special Rapporteur received credible reports that his death may have been due to a wilful denial of medical treatment of his leg wound while in custody. The man’s death may constitute not only murder, but also torture. The Special Rapporteur on torture has previously highlighted, “It is well established by numerous decisions by the UN Committee against Torture and other relevant monitoring bodies that torture can be committed by omission.”

The Special Rapporteur has seen photographs showing soldiers of Light Infantry Division (LID) 33 involved in the security forces’ response to protesters in Mandalay on 20 February, including soldiers with sniper rifles. According to security analysts, LIDs, including LID 33, can be deployed as mobile units directly subordinate to the Commanderin-Chief. LID 33 has a history of engaging in human rights abuses, including participating in extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, and sexual violence against ethnicRohingya civilians in Rakhine State in 2017, and against civilians in Kachin and northern Shan states.

According to medics on the scene in Mandalay on 19 February, security forces injured at least 40 individuals, most from gunshot wounds.

Adult male, murdered in Yangon: On 12 February, as part of a general amnesty, the SAC released more than 23,000 prisoners convicted of crimes. Following their release, the Special Rapporteur received numerous reports of assaults and robberies accompanied by unverified instances of arson and vandalism. In one instance recorded in video, residents of Yangon’s Sanchaung township detained four individuals who said they had been paid to break into homes at night.

So-called “neighborhood watch” committees have sprung up throughout Myanmar based on the well-founded fear of assaults and criminal activity by suspected junta proxies and police-led night-time raids and arbitrary arrests. Neighbors share intelligence on movements of soldiers and police, as well as the presence of unknown individuals. When residents spot police or possible proxies in their neighborhoods, residents bang pots and pans to warn their neighbors.

A thirty-year-old male, married with a five-year-old child, was one such volunteer neighborhood sentry in a Yangon suburb. On 20 February, he was standing guard when police arrived following an argument between him and a group of individuals sympathetic to the military. According to witnesses, an unmarked police car arrived at the scene and the victim asked the police why they were in the neighborhood. The police then cursed at him and reportedly fired three shots, one to his head, killing him instantly. The Special Rapporteur has seen photographs of the victim with the fatal head wound. The post-mortem analysis reportedly concluded that the bullet entered the back of his head and exited from the right eye, indicating he had been shot from behind. The police have reportedly refused to open an investigation.

At least 18 individuals killed in Yangon, Dawei, Mandalay, Myeik, Bago and Pokokku, 28 February 2021: On 22 February, the junta publicly pronounced on state television: “Protesters are now inciting the people, especially emotional teenagers and youths, to a confrontation path where they will suffer the loss of life.” On 25 February, military-backed counter-protesters engaged in violent attacks against protesters, most notably in Yangon, stabbing and beating unarmed individuals in chaotic scenes on city streets. Then, beginning on the evening of 25 February, Myanmar security forces began a stronger crackdown. Police in Yangon charged protesters without warning and used tear gas and rubber bullets, which to that point had been used in areas outside of Yangon.

On 28 February, Myanmar security forces dramatically increased the use of deadly force against protesters in at least six separate cities throughout the country. The Special Rapporteur received credible reports of murders, including those involving police and military forces firing into crowds of hundreds of protesters in the southeastern city of Dawei, shooting fleeing protesters in Mandalay and killing another woman seemingly at random while walking on the street, and lethally targeting protestors in Yangon.

These most recent killings demonstrate that Myanmar forces are now engaging in systematic murders throughout the country. Security forces in disparate locations are unlikely to have engaged in these murders on the same day without express approval of the senior-most leadership of the junta, including Min Aung Hlaing. As investigations are conducted, liability should extend to those highest in the chain of command in accordance with international law.

– global bihari bureau