A wildfire is an unusual or extraordinary free-burning vegetation fire that poses a significant risk to social, economic, or environmental values. It may be started maliciously, accidentally, or through natural means.

There is no universally agreed-upon terminology to describe fires, but they are often categorised in terms of the vegetation or “fuel” type in which they burn (e.g., forest, shrub, grass, peat, etc.), their behaviour and the severity of their impacts. Very often the more generic “wildland fire” is used. In some regions, “forest fire” is used for any landscape vegetation fire regardless of whether it is burning in a forest or not. In Australia, “bushfire” is common, where “bush” is a colloquial term for a landscape outside of urban locations.

As vegetation fire is endemic to many parts of the world, wildfires are those beyond the common fire occurrence and impact, and thus likely to be a cause for concern.

Many of the regions traditionally associated with frequent fire have shown a decrease in the burnt area over the last five years (e.g., areas in sub-Saharan Africa and northern Australia), while fires in some regions previously not considered fire-prone have increased (for example, northern India, Russia, and Tibet).

Over the last decade, it appears that more wildfires are occurring, not only in regions where seasonal fires are common but also in areas where fires do not normally occur. For example, eastern Australia and the west coast of the United States of America (USA) generally experience frequent summer fires, but the 2019–2020 fire season saw record-breaking numbers and extent of wildfires in these regions. The Arctic and the Amazon, however – areas not generally prone to extensive wildfires – experienced record-breaking blazes in recent years.

A common factor in these fire events is the persistent hot, dry, and windy conditions such as those that occurred around the world in 2019–2020 – the year 2020 tied with 2016 (which was helped by El Niño driving global temperatures) as the hottest year in recorded history. As human-induced global warming increases so does the frequency and intensity of the weather conditions conducive to wildfires. When combined with increases in other factors such as the number of ignition sources and high levels of available fuel, the threat of wildfires becomes extreme.

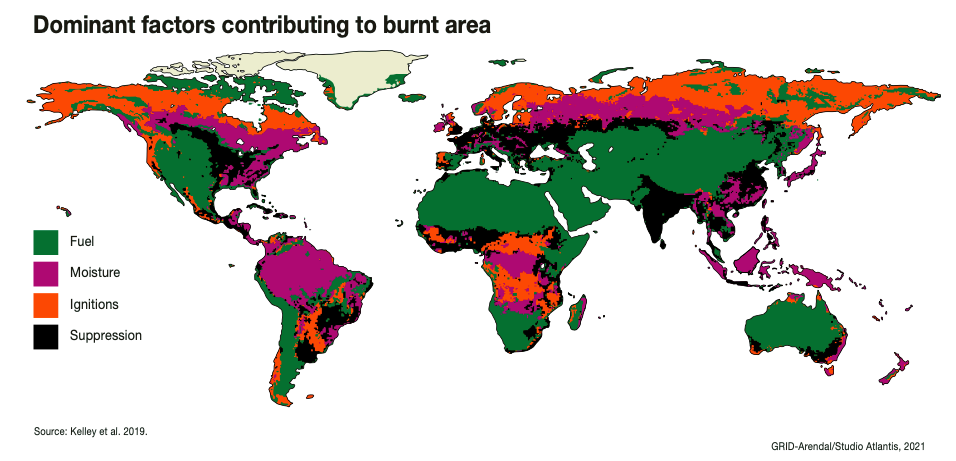

In many regions of the world, the presence of sufficient available fuel to carry fire is the dominant factor (the green areas in the above figure), whereas in others it is a sufficient source of successful ignition (the red areas in the above figure). In some tropical and subtropical zones, the dominant factor influencing burnt area is fuel moisture, meaning that while fuel and ignitions may be sufficient, fuels are often not dry enough to combust. Curtailment of fires through fire prevention, active suppression, or land-use fragmentation can be the controlling factor in developed regions.

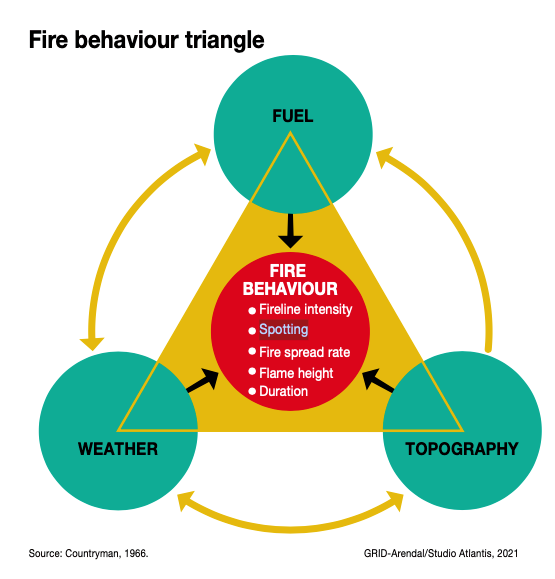

Where fire is an important ecological component of an ecosystem, and where some broad level of stability exists in the severity, spatial and temporal occurrence, and impact of fire, fire ecologists describe a characteristic “fire regime”. The components of such a regime include the types of ignition sources, frequency, intensity (energy output), severity (the effect of fire on the ecosystem), extent, seasonality, and heterogeneity (patchiness). Understanding the factors that can alter the fire regime of an ecosystem can help determine potential changes in fire behaviour and thus the likely impact of fire upon an ecosystem over a given period.

Current evidence points to a dramatic shift in fire regimes worldwide. This is driven by a combination of land-use change and climate change, with potentially widespread Earth system impacts on humans, vegetation dynamics, atmospheric composition and radiative forcing, and even ocean biogeochemistry and ice melt.

Impact of human-induced landscape change on global fires

How humans adapt and manage the land is one of the biggest influences on global fire regimes. Anthropogenic land-use change generally refers to converting land, often forest, for agricultural use – i.e., crops, pasture, or rangeland. Land-use change can also refer to afforestation (e.g., establishing plantations on former agricultural land, replanting with different species, or rewilding with nonextant species). Locally, the impact of land-use change alters the dominant vegetation and fire dynamics.

Land-use change can act as a source of wildfire ignition where, for example, people use fire to clear forests or manage agriculturally productive areas or temporarily increase fuel loads (for example, the build-up of forest debris after logging).

Land-use change can also increase landscape fragmentation, with different impacts in different biomes. In dense forest biomes, fragmentation can introduce higher flammability and increase the number of ignition points. Conversely, in savanna areas with sparse vegetation, fragmented connectivity between fuels inhibits fire spread which can limit fire size. Increased fragmentation in the savanna, particularly in the Sahel in North Africa, which experiences widespread annual burning, is the primary driver of the substantial and sustained reduction in the global burnt area over the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This reduced burnt area can alter vegetation assemblages and carbon uptake.

Agricultural intensification can also result in fewer wildfires due to a reduction in available fuel (e.g., from animal grazing) or increased active suppression. In many locations, including large parts of India, south-east China, temperate Europe, the American Midwest and South America, extensive agriculture has almost wholly inhibited wildfire (as opposed to fires lit for land management purposes). However, land-use changes such as abandonment and reforestation can drive an increase in burning, as seen throughout North America and Europe, and in tropical forests.

Land-use change can also have a substantial impact on the regional climate. Deforestation has been shown to reduce evapotranspiration and cloud cover and decrease precipitation. The resultant drying can increase fire conditions.

Excerpts from Spreading like Wildfire – The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires. A UNEP Rapid Response Assessment. Nairobi. United Nations Environment Programme (2022).

– global bihari bureau