Land-use change and fire feedback loops in Cambodia

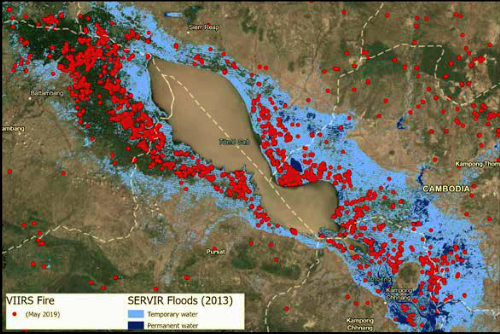

Tonlé Sap in Cambodia is the largest lake in Southeast Asia. Every year during the wet season, it floods and is then partially drained by seasonal “pulses” which occur when the flow of water between the lake and the Mekongn River changes direction. During the wet season, many of the lake’s 200 fish species move into the adjacent, newly flooded forests and grasslands to breed and spawn. As a result, this ecosystem supports one of the world’s most productive inland fisheries and is Cambodia’s primary protein source. Fishing is the only source of income for more than 100,000 people living in floating houses on the lake. The lake itself is also home to dozens of globally threatened species and is Southeast Asia’s largest waterbird colony. However, like many of the world’s largest lakes, it is rapidly shrinking due to climate change, upstream damming, and diversion of tributaries for crop irrigation. A significant fire feedback loop is compounding this situation.

Tonlé Sap in Cambodia is the largest lake in Southeast Asia. Every year during the wet season, it floods and is then partially drained by seasonal “pulses” which occur when the flow of water between the lake and the Mekongn River changes direction. During the wet season, many of the lake’s 200 fish species move into the adjacent, newly flooded forests and grasslands to breed and spawn. As a result, this ecosystem supports one of the world’s most productive inland fisheries and is Cambodia’s primary protein source. Fishing is the only source of income for more than 100,000 people living in floating houses on the lake. The lake itself is also home to dozens of globally threatened species and is Southeast Asia’s largest waterbird colony. However, like many of the world’s largest lakes, it is rapidly shrinking due to climate change, upstream damming, and diversion of tributaries for crop irrigation. A significant fire feedback loop is compounding this situation.

As the lake shrinks, people are burning formerly flooded forest to clear the land for rice farming. This is the main driver of fires in the Tonlé Sap Biosphere Reserve (TSBR). Meanwhile, Cambodia’s climate is warming, especially during the hottest, driest months (March–May). In a feedback loop, the clearing of seasonally flooded forests results in an even warmer and drier climate, leading to more intense and frequent fires and further tree cover loss, as observed in other tropical systems.

Between 2008 and 2018, approximately 2,800 km2 of seasonally flooded habitat in the TSBR was lost to expanded dry-season rice cultivation. The water that rice farmers use for irrigation no longer flows into the peatland swamp forests where it would have supported fish, fishers, and wildlife, and soaked the peaty soil to protect against forest fires. In 2019 and 2020, traditional fishing grounds remained dry, whereas in previous years the floodplain forests were inundated. Sedge beds extended up to 3 km from the lakeshore into what had previously been open water. As a result, fires increasingly burn out of control, destroying large areas of flooded forest that are then converted to agricultural land, continuing the cycle. These trends could lead to the complete loss of the Tonlé Sap Lake, with catastrophic economic, political, and biological impacts.

Without adequate and appropriate control, forest fires in the TSBR, Southeast Asia and the Asia-Pacific region will continue to adversely impact health and livelihoods, destroy biodiversity, and contribute to climate change. In this part of the world, people cause most ignitions, so a technology-centred approach to addressing forest fires will fail.

To control fires, governments need to be proactive. Instead of playing catchup, they should define an acceptable level of burning, where and when burning can occur, and the level of acceptable risk. An approach that involves community-based fire management which operates locally, drawing on assessments of social, economic, cultural, and ecological conditions can be employed to minimise damage and maximise fire benefits. This more proactive approach can complement the efforts of the government and build an effective partnership in forest management and protection.

Excerpts from Spreading like Wildfire – The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires. A UNEP Rapid Response Assessment. Nairobi. United Nations Environment Programme (2022).

– global bihari bureau