The Shankaracharyas at the confluence of Ganga, Yamuna and mythological Saraswati rivers in Prayag during the Kumbh 2025.

For centuries, scientists have been baffled as to the origin of the invisible Saraswati River at Prayag as there is no surface water flow. Some geologists have proposed that the Saraswati River originated over 4000 years ago through gigantic tectonic activity which caused gradient shifts and huge subterranean cavities in the earth. The proposition is that these tectonic shifts caused the Vedic Saraswati, which originated in the Himalayas and merged into the Arabian Sea, to flow beneath the earth’s surface.

The findings of our study have unveiled the mystery of the Saraswati River at Prayag and also opened a new scope for further detailed geoscientific investigations in the area in order to explore more about this mythical river and its future management. The unseen Saraswati River at Prayag is but a subterranean flow!

But before dwelling on our findings, let’s first talk about the Vedic Saraswati River. Legend has it that the ancient pilgrimage centre of Prayag is situated at the confluence of three rivers: the Ganga, the Yamuna, and the invisible Saraswati. The now extinct, Vedic Saraswati River, has been detailed in ancient texts such as The Rigveda, The Yajurveda, The Mahabharata, and The Puranas. Historical records and mythology, as well as geological, geomorphological, geophysical, archaeological, and remote-sensing studies conducted during the 19th and the 20th centuries, and in recent decades, demonstrate that the Vedic Saraswati River was a mighty river that drained large swaths of western India where the modern, Indian states of Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Gujarat are now located. There is a consensus among researchers that the modern Ghaggar River bed in western India formed much of the course of the Vedic Saraswati River. It is argued that the Vedic Saraswati River flowed sub-parallel to the Indus River and debouched into the Arabian Sea in the Kutch region of what is now Gujarat.

Studies of the paleochannels of the rivers in western India using remotely sensed data and dating of the zircon grains from the sands of the rivers reveal that the Vedic Saraswati, in its glory, was fed by the Satluj, the Beas, and the then westerly-flowing Yamuna rivers. Tectonic deformation in the Himalayan foothills in the Ropar area and on the eastern flanks of the Satluj-Yamuna mega-alluvial fan caused progressive deflection of the Satluj towards the west and of the Yamuna to the east. The reorganization of the drainage adversely affected the catchment of the Vedic Saraswati, which lost its glacial source of water and became a rain and groundwater-fed stream. The weakening of monsoons and the increase in the aridity of North West India in the Middle Holocene Era led to the further dwindling of the flow of the Vedic Saraswati. The river, which earlier reached the Arabian Sea, was reduced to a trickle and lost its way in the Thar desert.

There is some belief among the scientific community that the reactivation of the Daudpur-Bibipur fault caused a diversion of more water to the Yamuna River in the east in comparison to that of the Saraswati River in the west. River piracy by the now easterly deflected Yamuna through its tributary, the Somb River might have caused the flow of some parts of the Saraswati waters to move toward the Prayag “Sangam”, through the pirate Yamuna, which led to the legend of the invisible Saraswati meeting the Ganga and the Yamuna at Prayag.

While Indian mythology has a strong belief in the existence of the Saraswati River at Prayag in the invisible form, scientific evidence for it was lacking. It was assumed that the Saraswati comes to the confluence from the subsurface (patal lok). In 2015, the Government of India formed a high-level committee headed by Dr K S Valdiya to investigate the existence of the mythical Saraswati at Prayag, but the committee could not conclude the presence of the Saraswati River at Prayag. Heliborne geophysical surveys were also conducted by the National Geophysical Research Institute (NGRI) around Prayag to explore the presence of the Saraswati River, but no conclusive results were established. However, the NGRI did delineate a prominent paleochannel near Prayag.

Picking up from there, we extensively conducted hydrogeological and geophysical investigations under the National Aquifer Mapping and Management Programme (NAQUIM) in parts of Bundelkhand, Madhya Pradesh, India. We carried out the investigations in parts of Baramalehara and the Baxwaha Blocks of the Chhatarpur district in the Bundelkhand region of Madhya Pradesh, India.

We found some major, hitherto undiscovered, sinkholes and dolines exist in the carbonate rock formation of the area. This study delineated various limestone cavities in the study area where exploratory boreholes were drilled and substantial water discharge (1.5 to 20 litres per second – lps) was found.

The findings, which have been extended to the area adjacent to the north east of the study area, appeared to have similar geological terrain as those shown on regional Google maps. The findings verified and correlated with these geological structures in adjacent areas which exist as a major lineament on Google satellite images. The occurrence of numerous sinkholes and cavities holding flowing water are indicative of a subterranean flow in the area through karstic limestone formations of the Bijawar Group and the Vindhyan Super Group. The limestones of the Bijawar Group exhibit numerous cavities, a few dry and the others saturated with water. The Bijawar Group is, in turn, overlain by the Proterozoic Vindhyan Super Group, which represents one of Earth’s thickest Proterozoic sedimentary basins, and consists of major geological groups and formations that expose multi-tiered sequences of porcellanite, conglomerates, quartzites/sandstones, shales, limestones, breccias, etc.

Our integrated scientific investigation combined hydrogeology, surface geophysics, geology and drilling in order to delineate the groundwater potentiality, particularly in the various sinkholes and cavities of carbonate formations, to gain a proper understanding of the direction and the extent of the groundwater flow in the study area.

The study revealed that there is a huge, subsurface water flow in a significant area that is associated with numerous sinkholes, cavities, caverns, etc. The study proposed that the subterranean flow is continued up to Prayag (UP). Here, the study’s results linked the origin of the Saraswati River at Prayag with major sinkholes (dolines), like Bhimkund, Arjunkund, Patalganga, Sadwa, etc., existing in the area’s carbonate rock formations. The higher elevation of Bhimkund (430 metres above mean sea level – amsl) indicates that the water flows towards Prayag (100 metres above mean sea level) subterraneously and converges in Prayag at the confluence of the Ganga and Yamuna rivers.

Our study area was associated with several, huge, underground sinkholes and limestone cavities (e.g., Bhimkund, Arjunkund, Patalganga and Sadwa Caves). These geological structures are unique and are characterized by irregular dimensions and shapes due to the collapse of the ceiling after the dissolution of the carbonate rock formations. The Bhimkund (24.4384760N, 79.3761220E), a major sinkhole and natural water pool (kund) is located near Bajana village in the Baxwaha Block of Chhatarpur district.

During the investigation, attempts were made to measure the depth of the Bhimkund through wire/rope, but the water level could not be established beyond 80 meters below ground level (mbgl). The depth of the water level in the kund was about 30 mbgl in February 2015. During the post-monsoon seasons, the water level rises to about 15 -20 mbgl.

The colour of the water in the Bhimkund is a fascinating indigo-blue. The borehole logs of the four exploratory boreholes at the Bhimkund show that shale is encountered generally from 0-3 metres, sandstone from 3-25 metres, shale from 25–32 metres, sandstone from 32–42m, and fractured, compact limestone from 42–89 m. The exploratory boreholes in the study area yield 1.5 to 20 litres per second of water discharge.

The Arjunkund (24.45650N, 79.207138890E) is another major sinkhole that appears to be a natural, underground water lake/reservoir. It is located near Pipariya Kalan village (Near Dhanguawn village) in the Baramalehara Block of Chhatarpur district. It is a flat-looking, vast reservoir developed in a cave with a water level of around 20 meters below ground level in February 2015. The water of this body is spread over a large area whose extent could not be ascertained due to the prevailing darkness in the caves. During the post-monsoon seasons, the water level rises by 10-12 m in various places.

An attractive, naturally enclosed depression (sinkhole), locally called the Patalganga (24.4398060N, 79.253830E), is located near Darguawan village (about 2 km left of Sagar–Chhatarpur road) in Baramalehara Block. The Patalganga has several associated cavities in the area which are also not accessible due to darkness and complex structures. At a distance of about 100 m into the cave, an extensive underground reservoir appears. It is reported that during post-monsoon seasons, the water level rises by 12-15 metres.

The Sadwa Cave (24.485440N, 79.272720E) is a natural, enclosed, elongated depression (cave) in carbonate rocks and is located in a hillock near the village of Sadwa of the Baramalehara Block. The Sadwa Cave contains many branches of cavities that are not accessible due to the darkness, dangers, and complexities. The Sadwa Cave is well approachable 400 metres to the left of the Sagar-Chhatarpur road. Within the Sadwa Cave’s system, the locals have established a small temple about 200 m from the cavity’s entrance. The cavity is almost dry with some water seepage in several places within.

In addition to hydrogeological investigations, we also conducted geophysical investigations comprising vertical electrical sounding (VES) and earth resistivity tomography (ERT) in these areas. VES is an electrical method used to investigate subsurface geological media. ERT is an electronically modified advanced procedure used to measure surface resistivity by applying electric currents and measuring developed potentials across multi-grounded electrodes through an electronic time-switcher device. VES provides one-dimensional subsurface information whereas ERT provides two and three-dimensional subsurface information.

The resistivity profiles obtained over the known sinkholes/cavities and their correlations with the lithology demonstrated the efficacy of the ERT method for subsurface cavity mapping. It was observed that many sinkholes and underground cavities, water pools, and reservoirs are associated with strongly weathered limestone showing karst topography. The overburden in this area comprises weathered limestone or weathered granites ranging down to the depths of 5 to 30 meters below ground level.

There are 6 to 15-metre fluctuations in depths to water levels in the existing sinkholes and cavities in the area of study. It seems that many of these sinkholes may be directly getting recharged through groundwater while some of these sinkholes might also get water through the existing surface water bodies or from the rivers in the area. Attempts have been made by many researchers and organizations to measure the actual depth of Bhimkund, but it could not be measured beyond 80 meters below ground level due to the speedy flow of the water at greater depths. However, the depth to the water level in Bhimkund varies from 18 to 30 meters below ground level.

Now, the question arises: if the groundwater of Bhimkund is flowing beneath the surface, then where is it going?

The general answer may be that either the flowing groundwater is going to some river as a subterranean flow, or it is going to the ocean. Since the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean are both over 1500 km from Bhimkund, this answer may not be feasible.

Hence, it is logical to assume that the flowing groundwater is feeding some river(s). However since the beds of the present rivers on the surface are quite shallow and the flow of the groundwater at Bhimkund is at deeper levels, the question remains

unanswered.

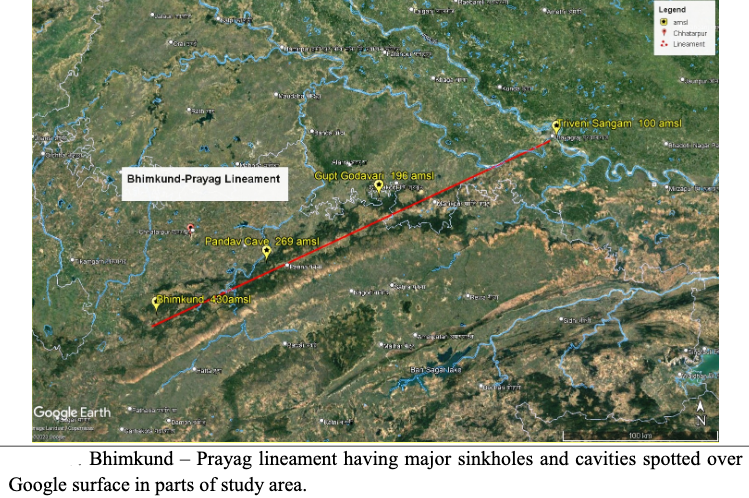

Interestingly, in addition to the cavities in the study area, adjacent areas have numerous limestone cavities that hold large quantities of water and also display flowing characteristics. The Pandav Caves near Panna and Gupt Godavari near Chitrakoot are prominent cavities wherein the underground water flows. Figure 7, a plot on Google Maps, shows these cavities with flowing water, and that these sinkholes/cavities are aligned along a prominent southwest-to-northeast trending geological structure (lineament). The map shows similar geological features all along its extension from Chhatarpur to Prayag.

We observed that a large number of sinkholes, water pools, caves, and caverns exist along this prominent lineament. The borehole drilling data of the Prayag area reveal that the basement rocks near the Ganga-Yamuna confluence are Vindhyan limestones. Based on the above observations, it can be assumed that this lineament represents an alignment of major cavities containing flowing water which are located within the carbonate rock formations; this phenomenon is characterized by subterranean water flow. The roughly 300 km long southwest to northeast lineament starting near Bhimkund in Madhya Pradesh’s Chhatarpur district, and ending at Prayag in Uttar Pradesh, can be termed the Bhimkund-Prayag lineament.

The general elevations along this major lineament at different cavities and locations are: Bhimkund 430 metres above mean sea level, Pandav Cave 269 mean sea level, Gupt Godavri 196 mean sea level, and Prayag 100 mean sea level. This indicates that the surface and subsurface water flows towards Prayag. There is a distinct gradient along the lineament from southwest to northeast. The water at Bhimkund is uncontaminated and clear, indicative of the flowing nature of water. The Gupt Godavari has observably clear, flowing water at 40 metres below the surface, but remains unknown where this water flows. Similar geological features and the water availability of these sinkholes and cavities all along the lineament may indicate that the Arjunkund, Patalganga, Bhimkund, and Pandav Caves, as well as many more cavities, are connected to the Gupt Godavari.

Thus, our study established a possibility of subterranean water flow through an interconnected network of sinkholes and cavities in the carbonate rock formations which constitute a southwest to northeast trending linear body.

This hidden subterranean flow meeting at the Ganga-Yamuna confluence at Prayag may be the invisible Saraswati River of Hindu legends (which is unrelated to the Vedic Saraswati River of western India).

Such long, subterranean, interconnected passages are not uncommon in carbonate rock formations. Examples of this are: the 686 km long Mammoth-Flint Ridge Cave System of Kentucky, United States of America, the 34 km long Kerem Liat Prah of Meghalaya, and the 3.5 km Belum caves of Andhra Pradesh (which is still being explored). Thus, the probability of the presence of a nearly 300 km long subterranean passage of water flow can be expected in this region, as well.

Linking our research findings with the outcomes of past studies and myths that prevail concerning the invisible Saraswati at Prayag, the current research postulates that ‘the unseen Saraswati River at Prayag is a subterranean flow which originates from the Bundelkhand region of Madhya Pradesh, follows the extensive, deep limestone cavities and caverns, and finally converges at the confluence of the Ganga River and Yamuna River at Prayag’.

*Former Regional Director & Scientist, Central Ground Water Board, Government of India. He conducted the studies to conclude that the mythological Saraswati River at Prayag is actually a subterranean flow.