Food habits of Indigenous People -4

Solomon Islands is a Melanesian archipelago of more than 600,000 people and more than 900 islands. The term Melanesian federates a diversity of tribes that are now organised according to their followed Christian movements.

This study was conducted at Melanesians inhabiting the Baniata village live in remote conditions in Rendova Island located in the Solomon Islands archipelago in the Pacific Ocean. Baniata was established as a village in the early 1800s, as a result of multiple numerous smaller villages of different tribes coming together. Up until a century ago, Baniata was almost completely self-sufficient, with community members relying mostly on homegrown and wild foods such as yams, bananas, taro, wild boars, possums and seafood. The arrival of the missionaries in 1915 led to the introduction of new foods including sweet potatoes and cassava, and the establishment of commercial coconut plantations. Seventh Day Adventist Church (SDA) arrived around 1920, influencing food production and consumption, including dietary exclusion of pigs, possums, eels and crustaceans.

Baniata, with a population of around 900, is a 90-minute petrol-powered boat ride from the nearest city and airport – Munda. Two smaller villages are within walking distance of Baniata: Havila, with a population of approximately 250, and Retavo, with a population of approximately 250. The three villages sit between steep mountain faces and the Solomon Sea. The climate of Solomon Islands is equatorial, characterised by heat and humidity, with distinctive wet and dry seasons. The temperature is consistently around 29 °C, with mild seasonal fluctuations, and rainfall varies amongst the islands, with the Western Province receiving the highest levels of approximately 3 000 mm per annum. Villages are surrounded by dense biodiverse bush, home to numerous native and endemic species.

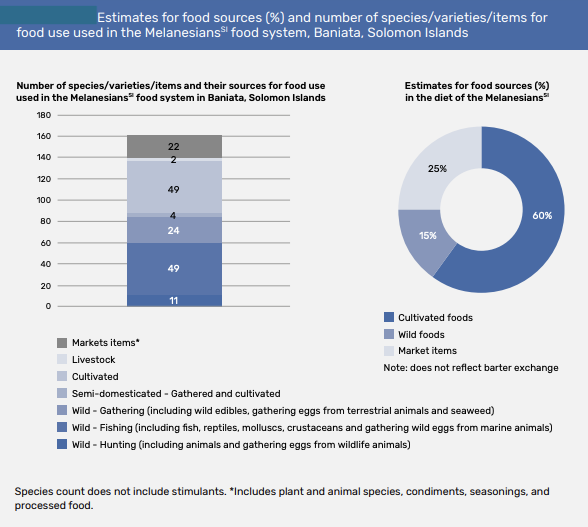

Baniata has over 127 food-providing species available for production, raising, collection from the wild, and ultimately consumption. Production systems include coconut plantations, food gardens, agroforestry systems, small amounts of domesticated livestock that are free-roaming chickens, hunting, fishing, and wild food harvesting. Homegrown foods are produced without agrochemical inputs, as villagers have expressed interest in maintaining organic production practices.

The original land-owning tribe of Baniata was Irurego, but currently eight different tribes live amongst one another there. Their food system relies primarily on the cultivation of tuber crops and banana in fields and home gardens. Inland agro-forests of fruit trees and ngali nut trees as well as coconut plantations along the shoreline for the production of copra are prominent components of the food system generating cash income. In addition, the food system relies on bushmeat and fish.

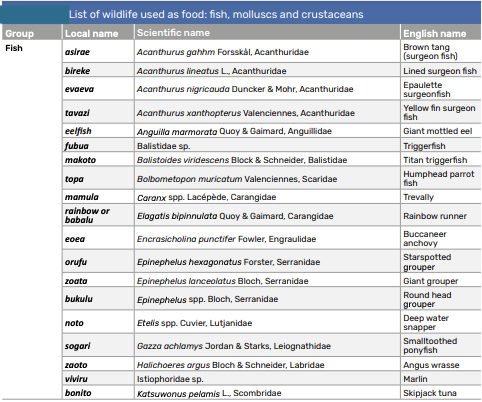

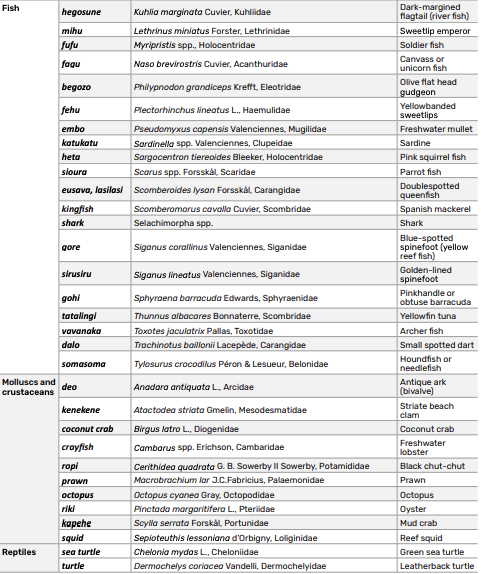

The Melanesian food system in Baniata consists of 132 species used as food, out of which 51 are aquatic species. In addition, multiple other species are used for nonfood purposes, such as for clothing, construction and materials, medicine, or fuel. Whilst the diversity of crops is declining, the local traditional varieties offer resilience against climate and pest disturbances, helping promote nutritious diets and access to diversified foods.

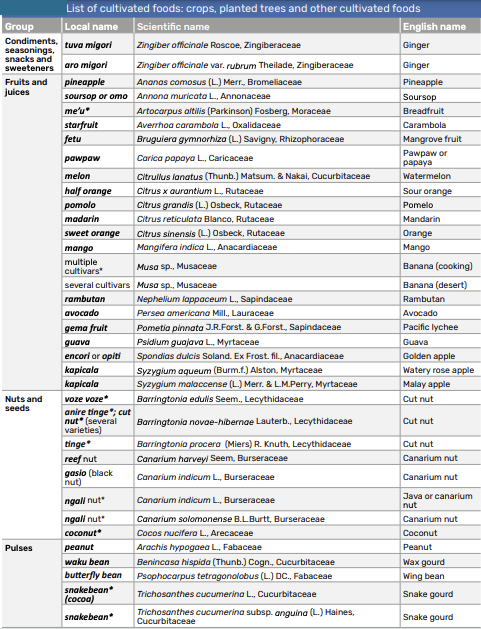

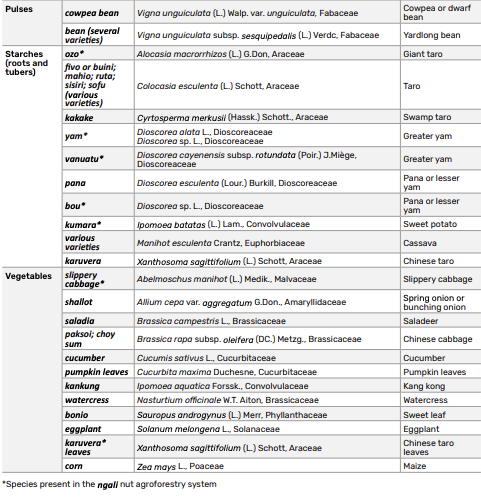

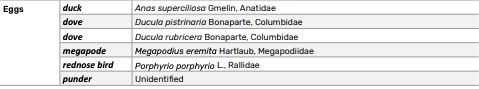

Home gardens produce roots, tubers, bananas, vegetables and fruits. Crop rotations and intercropping techniques are often practised. Ngali nut trees (Canarium indicum) are reported to be a significant source of both nutrition and income. Since domestication, they are planted with companion crops such as karuvera (Xanthosoma sagittifolium, Chinese taro), yams, bean and shade-tolerant cassava. In total, 19 different crops are intercropped with ngali nut agroforestry. The nuts are also a primary source of food for ghausu (doves), which are raised as a food source for the villagers. Coconut is planted along the shoreline of the village and used for agri-food sales, as well as consumption in forms of coconut milk and water.

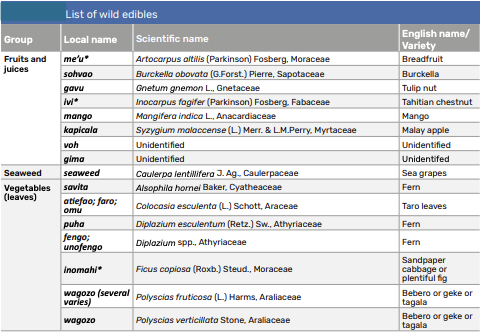

Wild harvesting of plants is a tradition in Baniata. Edible plants and fruit were previously a regular source of food, but the frequency and amount of wild foods harvested has declined over the previous three to four decades.

However, wild foods are more heavily relied on when villagers are harvesting ngali nuts, camping away from the village, or during times of travel. Few wild foods are sold for income generation. Starchy foods collected include wild yam, wild taro and wild breadfruit. Wild foods collected for consumption include green leafy vegetables such as ferns.

![]()

Fruits harvested from the wild include voh, gima, sohvao and wild mangos. Voh is a sweet and juicy yellow flesh fruit, and is said to cause itchiness. Its season coincides with the ngali nut harvesting season, and it is often consumed during the collection of the nuts. Other wild foods include ivi (Inocarpus fagifer, Tahitian chestnut) and a gavu (Gnetum gnemon, tulip nut).Many wild plants have non-food uses, including clothing, construction, bags, medicine, fuel and bedding.

Hunting and fishing are fundamental activities embedded with cultural and traditional importance, despite becoming progressively less prominent within the food system. One fourth of the food resources are sourced from markets and local stores, where handicrafts and garden products are sold and highly processed and imported foods purchased.

Traditional knowledge guides fishing: full moon is the best time for catching ghohi (Sphyraena barracuda, barracuda) and mara (Caranx spp., trevally); new moon, especially from the first to the fourth day, and on the seventh day, is best for fishing generally; and June and July are the best months to catch Kingfish. The primary seafood caught is bonito (Katsuwonus pelamis, skipjack tuna), turtles, sharks and eels; however, over 51 different aquatic species were fished locally. Villagers are able to keep any size of fish caught. Fish is consumed fresh, with only a few villagers smoking fish for preservation.

To catch fish, a rope is crafted from the inner bark of a pusi tree. The bark of this tree is flexible and can be easily tied to a bamboo pole with a traditional hook known as a zuahango. Occasionally villagers will use a poisonous plant, buna or deris, as bait to kill fish.

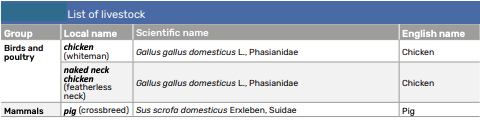

Livestock in Baniata was previously more productive, with chickens and pigs raised in fenced areas, but now primarily consists of free roaming chickens and a few domesticated pigs. The featherless neck chicken breed, which has an increased tolerance to heat, was introduced in 2016.

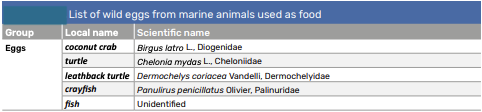

It is not uncommon that men catch young wild pigs and raise them until they have grown large enough for slaughter. Chickens are raised both for their eggs and meat. Non-seafood-animal-sourced foods are consumed once a month or less, and reserved for special occasions such as birthdays, marriages, Christmas and New Year’s. All animals are processed and consumed within the community.

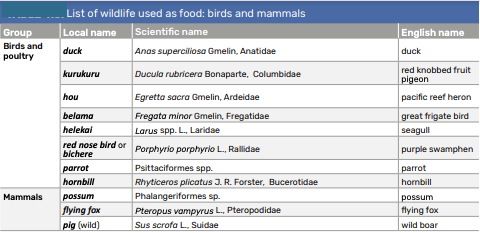

Wild game is hunted in lowland forests and mountain ranges beyond the village. Spears, bows and arrows are used. Hunting is still common, although declining due to less interest from the youth. Wild boars are hunted for celebrations and are sometimes sold at the market. They are targeted if they destroy gardens or eat ngali nuts from the forest floor.

Wild boar hunting techniques include the use of spears, traps and domesticated dogs (up to five at once). Other wild species hunted in the bush include parrots, bias (red nose bird), flying foxes (bats) and possums. These are typically caught with slingshots or bows and arrows. Fresh water invertebrates are also collected for consumption.

Excessive logging and reliance on the market have been the major drivers of change for the food system in Baniata over the second half of the past century, resulting in natural resource degradation and a greater dependency and consumption of imported and highly processed foods.

The reduction of the period for land fallowing and the intensification of agriculture have reached their limits. Increased pests and diseases along with climate change have impaired the health of the food system, resulting in further accentuating the dependency of imported highly processed foods. All of these factors are severely impairing the Melanesians agri-food system in Baniata village.

Major changes occurring in recent years:

- colonization has impacted cultural and religious beliefs and encouraged introduction of new foods and crops;

- monetization of the local economy and abandonment of traditional barter and exchange practices;

- increased import of highly processed foods and health deterioration with increase of non-communicable diseases; • reduced yields for crops and increased crop damage by pests;

- loss of traditional knowledge, in particular regarding hunting;

- declining stock of marine fish.

Trends expected by the Melanesians in future years:

- concerns about their increased demography in a context of limited land resources and damaged natural resources;

- imported rice anticipated to replace traditional tuber staple foods;

- climate change is feared to negatively impact agricultural yields;

- dependence on the market is expected to increase.

(Source of the article and data: Indigenous Peoples’ food systems: Insights on sustainability and resilience from the front line of climate change (Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations)

– global bihari bureau

Wonderful views on that!

That’s a great point

I didn’t know that.

A person essentially helps to make seriously posts I would state. This is the first time I frequented your web page and thus far? I am amazed by the research you made to make this particular publication amazing. Fantastic job!