This year’s International Day of Forests observance takes place during the first year of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration which focuses on scaling up efforts to prevent, halt and reverse the degradation of ecosystems worldwide and raising awareness of the importance of successful ecosystem restoration

Rome: Forests cover just over 30 percent of the global land area, yet they contain an estimated 80 percent of the world’s territorial biodiversity, home for most of the plant and animal species known to science. More than 1 billion people depend on forest foods and 2.4 billion people use fuelwood or charcoal to cook their daily meals. In developing countries, up to 80 percent of all medicinal drugs are plant-based.

Besides, drylands, often considered as barren, remote and unproductive, contain 1.1 billion hectares of forest, or approximately 27 percent of the world’s forest area and dryland forests offer food, medicines, energy, fodder and fibre to local communities. Non-wood forest products enhance food diversity, contribute to nutrition and improve food security, particularly during periods of drought and other food crises. In Africa alone, dryland forests and other wooded lands are estimated to meet a large part of the needs of 320 million people. Dryland systems contain 44 percent of the world’s agricultural land (58.4 percent of which is in Africa alone) and supply about 60 percent of the world’s food production. Drylands support over 50 percent of the world’s livestock, which is the main source of income for about 25 million pastoralists and 240 million agropastoralists. They play a vital role in global climate regulation as they store approximately 46 percent of global carbon reserves Moreover, globally over 30 percent of urban areas and 34 percent of urban populations are found in dryland regions.

There is also an urgent need to improve the management of the world’s drylands to ensure food security and healthy livelihoods. “Healthy forests mean healthy people. Forests provide us with fresh air, nutritious foods, clean water and space for recreation, and also for civilization to continue,” the Director-General of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), QU Dongyu, said today while opening the high-level ceremony to mark the International Day of Forests that is observed on March 21.

Yet, despite their importance, the area of forests continues to shrink. FAO’s most recent Global Forest Resources Assessment states that each year, the world loses more than 10 million hectares of forest – an area about twice the size of Costa Rica.

“We can change this. We have the knowledge and the tools,” said Dongyu, adding that restoring forests – and managing them more sustainably – was a cost-effective option to provide multiple benefits for both people and the planet. “Investments in forest restoration” Qu continued, “will contribute to economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic by creating green jobs, generating livelihoods, greening cities, and increasing food security.”

To meet global restoration needs and recover degraded forests and landscapes, adequate public and private investments were required to support restoration activities on the ground. FAO today also launched the report, Local financing mechanisms for Forest and Landscape Restoration to highlight financing opportunities for restoration that support local-level actors, including smallholder farmers, foresters and landowners.

To meet global restoration needs and recover degraded forests and landscapes, adequate public and private investments were required to support restoration activities on the ground. FAO today also launched the report, Local financing mechanisms for Forest and Landscape Restoration to highlight financing opportunities for restoration that support local-level actors, including smallholder farmers, foresters and landowners.

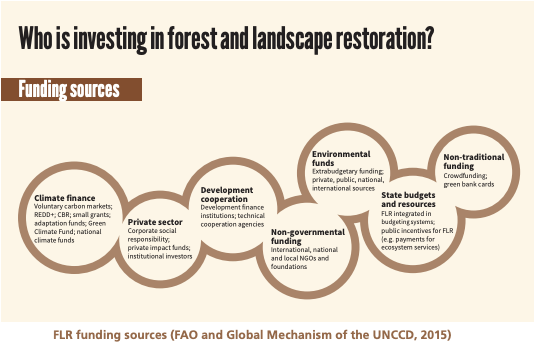

As per the report, to achieve ambitious international targets related to forest and landscape restoration (FLR), significant investment was required. It pointed out that annually, more than USD 36 billion was needed to meet the Bonn Challenge (a global goal to bring 150 million hectares of degraded and deforested landscapes into restoration by 2020 and 350 million hectares by 2030), and USD 318 billion to reach land degradation neutrality. While investment mechanisms for forest conservation are well established, mechanisms that specifically target restoration objectives are still being explored and developed.

The report acknowledged that FLR activities were often seen as risky investments, especially in highly degraded landscapes where the return is minimal or slow. “Initial upfront costs are often high risk and therefore predominantly financed by not-for-profit financial mechanisms, such as public investment and grants,” it noted. However, it pointed out that during growth phases, as FLR activities were implemented at the local level, risk was reduced and speciality funds such as loans could be more applicable. “As FLR landscapes are restored and investment risk is significantly reduced, other, more risk-averse financial investments, such as equity investments can be accessed, together with the development of market mechanisms such as NTFP (Non-timber forest product) development and PES (Physical and Environmental Sciences),”it concluded.

The FAO Director-General said that “Forest restoration offers us a solution to build back better and achieve the future we want. Let us all become part of the ‘Generation Restoration’ and restore the planet for better production, better nutrition, better environment and a better life. And finally, we can have a better world, a better civilization to continue.”

There is also an urgent need to improve the management of the world’s drylands to ensure food security and healthy livelihoods. Covering 41 percent of the global land area and home to 2.7 billion people, drylands supply about 60 percent of the world’s food production and support more than a quarter of forests and woodlands.

There is also an urgent need to improve the management of the world’s drylands to ensure food security and healthy livelihoods. Covering 41 percent of the global land area and home to 2.7 billion people, drylands supply about 60 percent of the world’s food production and support more than a quarter of forests and woodlands.

With four billion people projected to be living in drylands by 2050, another publication –Building climate-resilient dryland forests and agrosilvopastoral production systems – which was also released today here, outlined the transformational change required to ensure the sustainability of food production systems under climate change and after COVID-19, which includes giving a greater voice to marginalized dryland populations.

Drylands are characterized by a scarcity of water, which makes both natural and managed ecosystems more vulnerable than elsewhere to climate fluctuation and unsustainable land use. For centuries, dryland communities have utilized a mix of traditional and autonomous adaptation strategies, shaped by limiting water scarcity, guarding soil productivity and annual subsistence from natural variation of dry spells. These communities are often marginalized from national development planning and policies due to the historical perception of drylands as wastelands.

![]()

Over recent time, drivers such as population growth and land development, without local community involvement, have resulted in increasing land pressure and in soil degradation. In many countries, dryland communities have lost their traditional tenure rights due to land tenure policies that ignore essential features of local governance, such as communal property, mobility and adaptation capacity. Thus, dryland communities often have lower and declining incomes, increased malnutrition, and poor health culminating in higher mortality rates and famine. With limited livelihood opportunities, migration from rural to urban areas, and trans-frontier regions often follows. The vicious cycle of exacerbating poverty, competition for land, and degradation of natural resources can result in social, ethnic, and political strife, which then reinforces the levels of poverty and limited access to resources such as water. The recent 2020 Global Report on Food Crisis (WFP, 2020) indicated almost 3.1 million people in arid and semi-arid lands (ASALs) were facing crises.

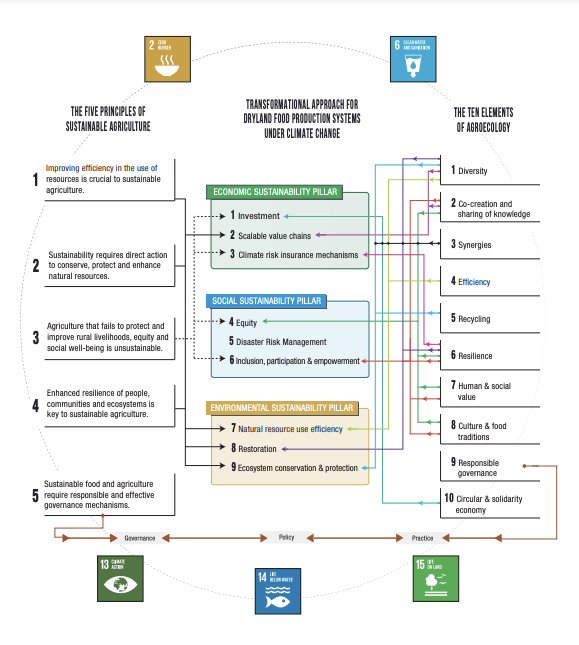

Given the vulnerability of drylands, the severity of the potential consequences of climate change, they are now also faced with negative impacts on food systems due to COVID-19, mainly in sub-Saharan countries, an increasing economic slowdown and further exacerbation of food insecurity and malnutrition. Therefore, there is an urgent need to build back better that allows for a better response to gaps in improving the dryland ecosystem adaptation and create more resilient food systems. “This can be done with an explicit approach to focus on economic insurance to address the inequality between rural and urban, poor and rich, and applying the gender lens. Environmental economics can contribute to understand trade-offs and co-benefits of planned interventions and thus promote making informed decisions and prioritizing activities or interventions among various alternatives,” says the publication, which brings together current trends, examples and experiences of changes in the management of dryland production systems that have, in different contexts and countries, contributed to meeting major environmental, social and economic challenges faced by dryland forests and agrosilvopastoral systems.

“It is however necessary to consider that informed decision-making and action must take place at the right scale, from policies to ground-level interventions, to ensure equitable and sustainable production in dryland forests and agrosilvopastoral systems. Baselines need to be established and the results from the different interventions periodically monitored, using indicators commensurate to the level and context of the interventions,” it states.

– global bihari bureau