[the_ad_placement id=”adsense-in-feed”]

First Person

– Nachiketa Desai*

– Nachiketa Desai*

Mahadevbhai had covered a vast range of subjects – from all major events of the freedom struggle to profiles of leading actors in them; from the ruin of the Indian economy under the British Raj to economics of khadiand village industries; from profiles of national leaders to pen sketches of unknown village constructive worker; from in-depth coverage of the Congress party’s sessions to analysis of national and international affairs; from literary criticism to commentary on media reports; from travelogues to human interest stories. Mahadevbhai was chronicling history as it was happening between 1917 and 1942.

For me Mahadevbhai Desai was just Dadaji. That he was also Mahatma Gandhi’s secretary for 25 years was, for me, incidental. I took some pride in the fact that Dadaji had translated Gandhiji’s autobiography, “My Experiments with Truth”, from Gujarati to English. I would boast to my classmates that the excerpts from the autobiography in our High School English textbook were my Dadaji’s writing.

[the_ad_placement id=”content-placement-after-3rd-paragraph”]

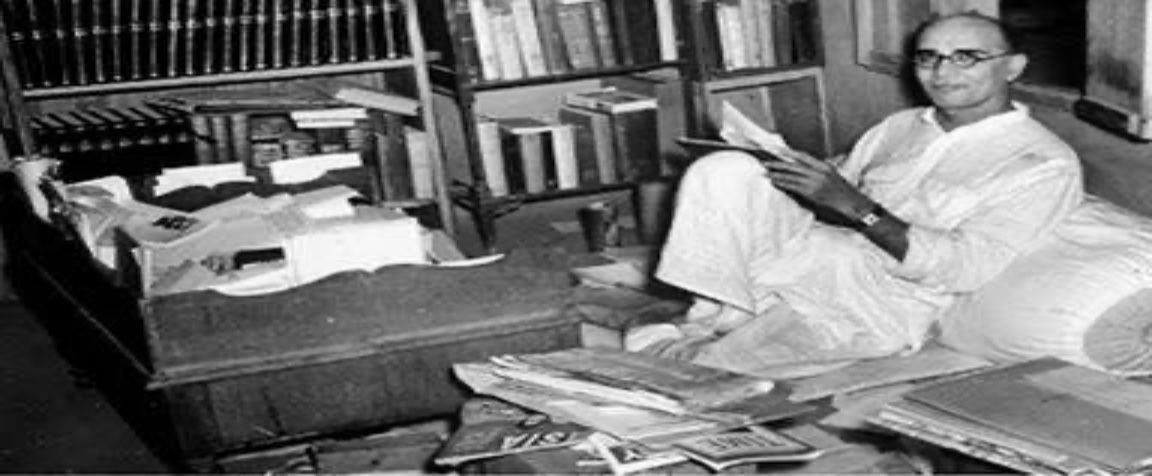

I had seen volumes of his diaries on the racks of my father’s cupboard. These were in Gujarati. I was not inspired to read them. The English translation of some of these diaries was also published under the series ‘Day-to-Day with Gandhi’. They too did not arouse my interest then. None of us grandchildren – my elder sister, younger brother and I – had seen Dadaji. We had only heard about him from our father Narayan Desai (we call him Babubhai). Tears would roll down our eyes whenever Babubhai read out to us from Dr. Sushila Nayyar’s memoirs the vivid description of Mahadevbhai’s death on August 15, 1942 in Aga Khan Palace, Pune. Our bonding with Dadaji was emotional, not intellectual.

Blame it on my ignorance that the intellectual facet of Dadaji registered on me much later in life, as late as in 1980. I was reading, ‘One Hundred Years of The Hindu’, the commemorative volume by the venerated newspaper. I was intrigued by the memoir of a former news editor of The Hindu in which he described how the news desk eagerly waited for Mahadevbhai Desai’s telegram conveying news about Gandhiji’s arrest at Palwal station on way to Punjab.

“Why should the news desk of The Hindu want Dadaji’s report?” I wondered. When I met Babubhai next, I asked him. “Don’t you know, Mahadevbhai was the Gandhi camp correspondent for the Associated Press of India (API)?” He would report Gandhiji’s speeches, delivered in Gujarati or Hindi, in his long running handwriting on a telegram form in English and despatch it to various newspapers,” he told me.

I was thrilled as the realisation dawned on me that Dadaji was also a newsman and not just Gandhiji’s secretary and biographer. He filed reports for the country’s first news agency, API which was later taken over by Reuters. This information excited me no ends as I too at that time was working for a news agency, the United News of India. Babubhai revealed that Dadaji had also worked as editor of The Independent, a daily owned by Motilal and Jawaharlal Nehru, in Allahabad.

Charged by such exciting information, I started looking at Dadaji’s life and work from a totally different perspective. Babubhai had also mentioned that Dadaji had a fairly large collection of books which, for want of space, were kept in safe custody at the Satyagraha Ashram at Sabarmati in Ahmedabad.

In the Sabarmati Ashram, there were 20 cupboards with books marked ‘Mahadevbhai Desai Granthalaya’ each carrying Dadaji’s signature. In one of the cupboards there were books only on journalism, grammar, idioms, phrases, the art and craft of writing. There were reference books like Encyclopaedia Britannica, Fowler’s English Grammar and dictionaries of Latin and French phrases. There was also Pitman’s English and Shorthand Dictionary.

There are over 3,500 books in Mahadevbhai’s collection. I had only a cursory glance at a few cupboards during my first visit after hearing about it. My preoccupation with work in a news agency and thereafter as a journalist with daily newspapers did not allow me the time to go through all the books.

An occasion to look closely at Dadaji’s life and work presented itself during Mahadevbhai’s centenary celebrations in 1992. A 30-member committee for the celebrations was formed under the chairmanship of former Prime Minister Morarji Desai of which I too was a member. It was decided to bring out a commemorative volume on Mahadevbhai besides biographies in small booklet form of his contemporaries – Narhari Parikh, J C Kumarappa, Kishorelal Mashruwala, and Miraben – who too shared their centenary with Dadaji.

While Babubhai undertook the task of writing the biography of Dadaji, I decided to bring out a book on Mahadevbhai’s journalistic writings. Babubhai had told me that Mahadevbhai, besides writing a newsletter under his initials M.D. in Gandhiji’s weeklies, Young India, Navajivan and Harijan, also contributed to various newspapers like The Hindustan Times, Bombay Chronicle, Fress Press, Amrita Bazar Patrika, The Hindu and The Illustrated Weekly of India. This he did as a freelance journalist when he needed some extra money to meet the needs of his family.

Babubhai, raised and educated in Gandhiji’s ashrams at Sabarmati and Sevagram under the direct supervision of Mahadevbhai and having imbibed the virtues of self-discipline and time management, completed writing the biography in the centenary year. The biography in Gujarati, titled ‘Agnikund Ma Ugelu Gulab’ (The Fire and the Rose), won the national Sahitya Academy award as the best biography in an Indian language. The biography was later translated into Hindi and English.

Writing the biography fifty years after the death of Mahadevbhai was a daunting task for Babubhai. “No doubt I was Mahadevbhai’s son, but I had stayed with him only for the last six years of his life. And those six years were those of my adolescence. They cannot be considered adequate for writing a biography,” wrote Babubhai about the difficulties he faced. “It was difficult to find his contemporaries who could give me heaps of material. Mahadevbhai was an inveterate correspondent, but his letters were not preserved by his family. Was it not a folly on our part? My mother had torn up the letters, off and on. Some must have gone astray because of change of residence and imprisonments,” he explained.

Mahadevbhai’s diaries were also not of much help as they were not his but Gandhiji’s. There was nothing about his personal life, not even a passing reference to his only son’s birth! The key to Mahadevbhai’s life, which was merged with Gandhiji, was to be found in Gandhiji’s writings – ‘The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi’, in which he figures in hundreds of places.

During his 25-year-long association with Gandhiji, Mahadevbhai had come in close contact and become friends with – Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Jawaharlal Nehru, C. Rajagopalachari, Devdas Gandhi, Pyarelal and a whole host of other national leaders. Babubhai found so much in the writings of these people about Mahadevbhai that it became a difficult task to select what to include and what not to include in the biography.

The challenge before me to discover Dadaji, the journalist, was somewhat different from what confronted Babubhai in his endeavour to write the biography. There was the 25-year-long period of prolific journalistic writings by Mahadevbhai in various publications spread across the country – Delhi, Allahabad, Kolkata, Ahmedabad, Mumbai and Chennai – besides reports that he filed for API which did not carry his by-line. Some of the dailies like the Bombay Chronicle, The Independent, Amrita Bazar Patrika and Free Press had ceased publication a long time ago. Others may, or may not have kept their archives. I realized to my utter dismay during my quest for Mahadevbhai’s journalistic writings that though we take much pride in our rich tradition and heritage as a nation, we have criminally neglected the preservation of archives.

The first obvious place for me to look was in the archives of Young India, Navajivan and Harijan of all of which Mahadevbhai was a regular columnist and the editor when Gandhiji was in prison. The archives of these weeklies are kept in the library of Gujarat Vidyapith, the university founded by Mahatma Gandhi in 1920 in Ahmedabad. While the pages of original prints of Young India and Harijan have been moth-eaten, torn and turned brittle, fortunately these have been reprinted and kept in bound volumes. Even then, some of the issues and pages have been lost forever.

Mahadevbhai’s contribution to these weeklies runs into thousands of pages. Besides the articles carrying his by-line M.D., Mahadevbhai has extensively reported in English Gandhiji’s hundreds of speeches delivered in Gujarati and Hindustani as also those of various national leaders such as Sardar Patel, Jawaharlal Nehru, C Rajagopalachari, C R Das, Mohammed Ali, Shaukat Ali and Rajendra Prasad.

A commemorative volume on Mahadevbhai titled ‘Shukra Tarak Sama’ (Like the planet Venus) in Gujarati, published in 1991 as part of his centenary celebrations, was the first major initiative to collect at one place the tributes paid to him by his contemporaries after his death. This included obituaries by Jawaharlal Nehru, C Rajagopalachari, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, Dr. Sushila Nayyar, Pyarelal, Swami Anand, Syed Abdullah Brelvi and Verrier Elwin.

While the focus of most obituaries was on Mahadevbhai’s dedicated service to Gandhiji as his alter ego, companion, secretary and spokesman, it was Swami Anand, his colleague in the editorial team of the weeklies Navajivan and Young India, S A Brelvi, his classmate in college who became the editor of the Bombay Chronicle, and Verrier Elwin, his friend and eminent anthropologist, who threw much light on his role as a journalist.

Then in 1992 came the voluminous and authoritative biography of Mahadevbhai by Babubhai. The biography titled ‘Agni Kund Ma Ugelu Gulab’ (The Fire and the Rose), as the title suggests, narrated the life of Mahadevbhai in the service of Mahatma Gandhi, which was like sitting atop a volcano. In his foreword to the biography, Gandhiji’s scholar grandson Rajmohan Gandhi described Mahadevbhai as one who lived Gandhiji’s day thrice over – first in an attempt to anticipate it, next in spending it alongside Gandhijji, and finally in recording it in his diary. “He therefore was Gandhi’s aide, secretary and interpreter, but this ‘correct’ description excludes the independent mind, conscience and pen that Desai supplied and Gandhi relied upon.”

The biography did touch upon Mahadevbhai’s role as the editor of Navajivan, Young India and The Independent and as a diarist. In a separate chapter on Navajivan, the biography has extensively quoted Mahadevbhai’s Gujarati articles and his trials and tribulations as the editor in place of Gandhiji who was in prison at the time. However, the biography has not detailed his role as a columnist, reporter and freelance journalist who, in the words of Verrier Elwin, was largely responsible for making Gandhi the most loved person in this world through his writings.

Assured that I would be able to access Mahadevbhai’s writings in the archives of Young India, Harijan and Navajivan, I decided to focus on locating sources from where I could find his articles in other publications. Ever since the availability of the Internet in the country, I had been routinely and at regular intervals searching for “Mahadev Desai”. It was in the early 2000 that I first came across a couple of websites which had ‘Mahadev Desai’ in them. These were only in reference to Gandhiji’s autobiography as its translator and then as the author of the book, “Gita According to Gandhi”.

Thus the information superhighway, as the Internet is called, did not lead me anywhere near M.D., the journalist, whom I was desperately trying to rediscover for my generation as well as the next. As the use of the Internet proliferated and authors and researchers started sharing their thoughts and writings through the world-wide web the name of Mahadev Desai began to appear in cyberspace more frequently. However, except for a cursory reference no website gave a fuller treatment to his role as a journalist.

When a search engine started putting up news archives of various dailies on the web for the first time I came across some of Mahadev Desai’s articles published in The Indian Express, Madras (those days the newspaper had only one edition from Madras). I also found in the archives news reports published in scores of British, American and European newspapers about his arrest, public meetings and bandhs observed in various parts of the country to mourn his sudden and untimely death in the Aga Khan Palace, Pune on August 15, 1942. These were in abstract form and were available in full only on payment of a fee.

The discovery and the prospects of finding more on Dadaji’s journalistic writings excited me and propelled me to take up research on a serious footing so that I could come out with a book on Mahadevbhai’s contribution to journalism. “Mahadevbhai’s independent personality got overshadowed in the reflected glory of Gandhiji. Imagine what a great writer and a journalist he would have been if he had not dedicated his life in the service of Gandhiji,” remarked Gopalkrishna Gandhi, Gandhiji and Rajaji’s grandson when I told him about my venture.

As my search for Dadaji’s journalistic writings progressed, I began to discover that Mahadevbhai had covered a vast range of subjects – from all major events of the freedom struggle to profiles of leading actors in them; from the ruin of the Indian economy under the British Raj to economics of khadi and village industries; from profiles of national leaders to pen sketches of unknown village constructive worker; from in-depth coverage of the Congress party’s sessions to analysis of national and international affairs; from literary criticism to commentary on media reports; from travelogues to human interest stories. Mahadevbhai was chronicling history as it was happening between 1917 and 1942.

*The writer is a senior journalist and grandson of eminent freedom fighter and Mahatma Gandhi’s personal secretary Mahadev Desai

[the_ad_placement id=”sidebar-feed”]