Spiritual Discourses: Free the mind from desires and emotions

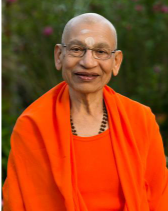

By Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati*

We must make a deliberate attempt to free the mind from desires and emotions. Whenever a desire arises, recognise that it is a product of ignorance. Every desire is an expression of an inadequacy born of ignorance. The need for happiness is an emotional need. The objects of the world can fulfill that need only to a certain extent. Beyond that, they cannot give us happiness or security. As desires arise in the mind, subject them to scrutiny; do not jump to fulfil them immediately. This is vairagya, dispassion. It involves analyzing the nature of every object of desire and recognizing its limitations through discrimination.

parikshya lokan karmachitan brahmano

nirvedamayannastyakrtah krtena.

Having examined the worlds that are achieved through karma, a contemplative person should become dispassionate. The uncreated is not possible through karma [Mundakopanisad, 1-2-12].

One must determine what one wants in life. Needs are never-ending. We are born needy and, as we grow, these needs grow as well. While the objects of need change, the need itself remains. No degree of accomplishment creates satisfaction; we are never comfortable with ourselves. Success is measured by the satisfaction with one’s self. Can one relax without needing to do something? Contentment is not something one can will; it has to happen, it has to be found. We cannot declare that we are satisfied. That requires a lot of hard work.

Living life intelligently makes us progressively satisfied. Material comfort should not become an end in itself. Ultimately, the measure of success is our degree of comfort and satisfaction with ourselves. Total success is in finding total comfort with ourselves. Desires are endless; therefore, keep a check on them. Whenever there is a desire, inquire whether the desire is for the thing itself or for a higher purpose. You will find that every desire is an attempt to become limitless; the endless cycle of desiring and fulfilling these desires is ultimately a search for completeness. Therefore, recognize that desires have to be fulfilled from within and not through any external source. Nothing else is capable of bringing about that fulfillment because your desire is for the limitless. You have to own up to the limitlessness that is your true nature. It is not enough that you are Brahman; you must know that you are Brahman. As long as you keep fulfilling your desires, your mind will remain extroverted. It cannot be comfortable with itself.

Furthermore, our present understanding of ownership also comes from false perception. When we analyze our possessions, we discover that we do not really own anything; Ishvara, the creator, is the owner of everything. We can then look upon the things of the world as gifts given to us for our enjoyment. Our attitude towards possessions such as a house etc., changes slowly. It is not that we become indifferent to these possessions, but we begin to realize that we do not own any of them; we only use them. This is detachment, the freedom from dependence. Lord Krishna says:

asaktiranabhishvangah putradaragruhadishu,

nityam cha samachittatvamishtanishtopapattishu.

…absence of ownership, absence of excessive affection regarding son, wife and house, and always evenness of mind regarding the gain of the desirable and the undesirable…[Bhagavad Gita, 13-9].

Gaining freedom from our possessions and excessive attachment to those related to us closely happens slowly. The sense of security provided by one’s family or wealth is an emotional need. Emotional growth is the process of becoming free from this need by discovering greater sufficiency in ourselves. One lives a life of retirement only when one is free from emotional needs. This does not mean that we have to give up everything. It is just that these things are simply of no concern any more. This is detachment. It is natural that things become important and occupy our minds because we are in the midst of them. It is difficult to remain detached in such situations. However, if that is accomplished, one does not need any other form of renunciation.

Assign some time to drop every activity and be with yourself; look at yourself, know yourself, know your personality. The deliberate attempt to make the mind free from desires and emotions is pratipaksha-bhavana, taking the opposite viewpoint.

In practising this, one deals with every emotion by deliberately assuming the opposite. For example, one would deal with anger through forgiveness and compassion. It would appear that jealousy arises from the perception that someone else is better than oneself. Yet it is not his accomplishment that makes us unhappy, but the sense of not being as well accomplished; it makes us aware of our perceived limitations and lack. It is this that causes a sense of inadequacy and pain. It makes us face something that we do not want to face within ourselves. The best way to deal with jealousy is to laud the other person’s success and be happy for them. Attempting to become happy through the happiness of others is a good way to become happy. Cultivate this habit deliberately and, in time, it will happen. You have to constantly watch and deal with the mind.

We are swept away by many things and have no leisure to watch our minds deliberately. Take time off to be with yourself and think. Get familiar with your mind and emotions and decide upon a strategy to deal with them. This is surrendering your reactions. There is freedom in that because all anger, jealousy, frustration, attachment, and aversion are expressions of bondage. To the extent that you let go of these emotions, you will discover freedom.

The desire for freedom must transform into a desire for knowledge

The stage of life when karma and bhakti are predominant is called pravritti. The life of a householder is that of karma-yoga or bhakti-yoga. As a householder, if one performs actions based on dharma and maintains an attitude of graceful acceptance, one acquires emotional maturity, inner growth, and freedom from many false notions. In this process, one begins to realize that the Limitless is gained not through becoming, but by knowing. This is when the desire for freedom gets transformed into a desire for knowledge. This important transformation has to take place for one to become eligible to receive and assimilate this knowledge.

We see this kind of transformation in Arjuna. He comes to the battlefield with a desire to fight and win. He equates victory with success. As he begins talking to Lord Krishna, he realizes that even victory can leave him incomplete:

na kankshe vijayam krishna na ch rajyam sukhani ch, kim no rajyena govinda kim bhogairjivitena vä.

O Krishna, I want neither victory, nor the kingdom, nor comforts. O Govinda, of what use are a kingdom, enjoyments, or even life? [Bhagavad Gita, 1-32]:

At one point, Arjuna tells Lord Krishna that even if he is made the king of the three worlds, he does not see how the pain that he is suffering can be removed. It is very clear to Arjuna that even the highest accomplishments cannot remove the sorrow that arises from a sense of incompleteness. That is how he submits himself to Lord Krishna and his teaching. He becomes a jignasu, one desirous of knowledge, from being a mumukshu, one desirous of freedom.

Upon deliberation, it becomes clear that ignorance is the cause of our wrong perception and, therefore, all our problems. Every problem is always spiritual in nature; the desire to be successful, to have one’s way, and to prove oneself arises from a fundamental spiritual problem. Sorrow and sadness are not material problems. Sorrow is a creation of the individual and the result of ignorance. It is a spiritual problem, and, therefore, there must be a spiritual solution for it. Until this is understood, one seeks material solutions for solving the problem of sadness.

But, every material solution has an inherent problem; no solution can prove to be a final solution. All our rearrangements can at best remove our discomfort. When we recognize the fact that there is no problem in our lives other than ignorance and the wrong perception created by it, we begin to value knowledge. Until then, it remains merely one of the many things that we value.

With time, one’s commitment to gaining knowledge gains importance. It may even lead to renunciation if you so choose. As one grows in maturity, one becomes free of needs. Detachment comes with the discovery of mithyatvam or the unreality of the things of the world. Mithya is what a thing appears to be. As long as we consider the things of the world as a source of security, they appear to be real. When we know of their unreality, the mind becomes free from attachment. Unless this mature relationship is present, we cannot enjoy freedom from these things.

Detachment is a preparation for renunciation. Usually, the mind remains attached even if a physical distance is created because of false perceptions and the importance given to worldly things. In the process of surrendering, this attachment also ceases. When the relationship with the world is comfortable and healthy, and not one of attraction and ownership, one is ready to give it up if need be or remain in one’s own place as a renunciate.

Renunciation is a gradual withdrawal from activity and an entry into a life of contemplation. Lord Krishna talks about two stages of renunciation: one, a life of activity (karma-yoga) that aids in spiritual growth and, the other, a life of contemplation that is the final stage of refinement. A significant tuning up of our minds takes place during the life of karma-yoga. Then the proportion of study, thinking, and contemplation increases. As we gain an interest and satisfaction in the pursuit of knowledge, other things drop off. This is the next stage of surrendering and discovering freedom.

The life of renunciation enables one to pursue knowledge exclusively

A renunciate enjoys freedom of mind because he is free from possessions and duties. This frame of mind is required for the study of the scriptures. As the Panchdasi [7- 106] points out, the study involves tat chintanam tat kathanam anyonyam tat prabhodanam, reflecting on It, talking about It, and mutually producing logical arguments about It. This is the life of a renunciate. It is a life of study and contemplation. In the Vedic times, students left the comforts of their home to live with their teacher. This is how the renunciation of karma, duties, became necessary. There is a surrender of all rights and claims when there are no duties. They could live on alms, and, therefore, they had freedom from possessions.

Knowledge is the result of vichara, deliberation, inquiry, or investigation into the nature of things. This requires a mind that enjoys leisure. The Mundakopanisad [1-2-12] says, tadvijnanartham sa gurumevabhigacchet, therefore, to attain knowledge, he must necessarily approach a teacher. The Vedas have two sections. The first section, the karma- kanda, talks about dharma, and the second, the jnana-kanda, reveals brahman. For the person living a life of activity, dharma is a means. The pursuit of knowledge under the guidance of a teacher is a life of contemplation and renunciation. This pursuit is most effective when the mind is sattvika. The ego is devoted to study and does not react. Doership and enjoyership, the products of ignorance, keep diminishing in the wake of listening to the teaching, shravanam. Vedanta says, tat tvam asi, you are that, brahman. You are limitless and whole. It is the teacher who helps us understand and own up to this fact.

Inner freedom is the recognition that one is brahman

Vedanta employs various methods to make us realize the error of our notions and explain the origin of these notions. It teaches the separation of the subject from the object; the drik-drshya-viveka. This is the separation of the seer or the subject from the seen, the object. Even though the subject and object are two distinct entities, they are taken to be one due to false identification. We are made to see that the body is not the subject; it is not the self, but an object of one’s perception. Just as we can say that everything that we see exists as an object in our awareness, so also, this body is but an object of our awareness. To say that one is the body is a habitual error. As Bhagavan Shankara says in the adhyasa bhashya, ahamidam mamedamiti naisargiko’yam lokavyavaharah, the beginningless ignorance is expressed in worldly transaction as ‘I am this’ or as ‘This is mine.’ One is born with the notions of ‘I’ and ‘mine’ arising from the identification with the body-mind complex.

Vedanta asserts that we have not deliberated upon our conclusions about ourselves. We have taken for granted that we are the body and mind, that we are needy, incomplete etc. How did we arrive at these conclusions? Just because we see or feel something, we cannot assume that it is right. Vedanta addresses the fundamental feeling that we are limited and mortal. If we associate ourselves with the body, we can only suppose that we are born with the body and will die with it. Yet the one who appreciates the birth and growth of the body is essentially different from the body. Therefore, we are not the body. The birth or death of the body is not the birth or death of the self. We are not the mind either. Happiness and unhappiness are particular states of mind. As the subject, the knower, one is aware of these states of the mind. The mind is thus also an object of our awareness and, therefore, we cannot be the mind. Sometimes, while watching a movie, we momentarily forget that we are spectators and become one with the characters on the screen. Similarly, when the mind comes up with the idea of happiness, we declare ourselves happy. This is due to our identification with the mind. In truth, our status is that of a spectator, an observer, the subject, the one who is aware of these states of the mind. At the level of the intellect, there are concepts like ‘I am a doctor’ or ‘I am a teacher’ etc. I, the individual, am aware of these concepts. The one who is aware of something is always different from that of which he is aware. The subject is necessarily different from the object.

It is not enough to say that what one takes oneself to be is wrong. It is also necessary to understand why one has this mistaken notion and where it originates. If we know where this false perception comes from, we can correct it. It is in the wake of the knowledge that one is the self, Ishvaroham, and that one is brahman and not a jiva that the final surrender takes place. This is the surrender of the most subtle of notions or false perceptions, such as ‘I am a doer’ or ‘I am an enjoyer’ etc. Then one is totally free.

Another dimension of the teaching is that all that exists is you. Even though this recognition begins with the understanding that one is the subject and not the object, the final insight is, that whatever exists is but the manifestation of yourself. There is no duality whatsoever. Once you gain this knowledge, there is no sense of distance, division, or separation. You do not feel excluded by anything. In this, there is total freedom. There are no projections or reactions. The Bhagavad Gita says [2-56]:

dukheshvanudvignamanah sukheshu vigatasprhah,

vitaragabhayakrodhah sthitadhirmuniruchyate.

The one who is not affected by adversities, who is without yearning for pleasures, and is free from longing, fear, and anger is said to be a wise person of firm knowledge.

In situations that are generally considered painful, such a one is free from reaction. In situations that are considered tempting, he is not tempted. He abides in his own self, in the wholeness that he is. When Lord Krishna completes his teaching in the Bhagavad Gita [18-66], He says, “Giving up all your notions and false perceptions, surrender unto Me. Discover that I am your very self. I will release you from all your pain.”

There is a freedom that emerges from total surrender. The surrender of one’s self is the surrender of the ego, the sense of individuality. Surrender becomes complete in the discovery that the notion of individuality is false and that the self one has taken to be small is, in truth, limitless and complete. There is no just cause for grief at all. All grief is a product of ignorance and, indeed, has no reality in the wake of knowledge.

*Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati has been teaching Vedānta Prasthānatrayī and Prakaraṇagranthas for the last 40 years in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. Throughout the year, he conducts daily Vedānta discourses, accompanied by retreats, and Jñāna Yajñas on Vedānta in different cities in India and foreign countries.