The increase in the demand for natural cosmetic and beauty products is good news for forest communities. Growth in natural cosmetics industries is at almost 10 per cent per year. This is providing forest communities with livelihood opportunities and also spurred interest in sustainability.

So if you are interested in natural cosmetic products, ones that support local communities and don’t deplete our natural resources, you aren’t alone! During the last decade or so the extent of natural ingredients used by the cosmetics industry has increased.

The beauty products found in forests

Growing consumer interest in the environmental and ethical credentials of cosmetics has also galvanized interest in ethically-sourced beauty products, which include many forest products, also known as non-wood forest products (NWFPs).

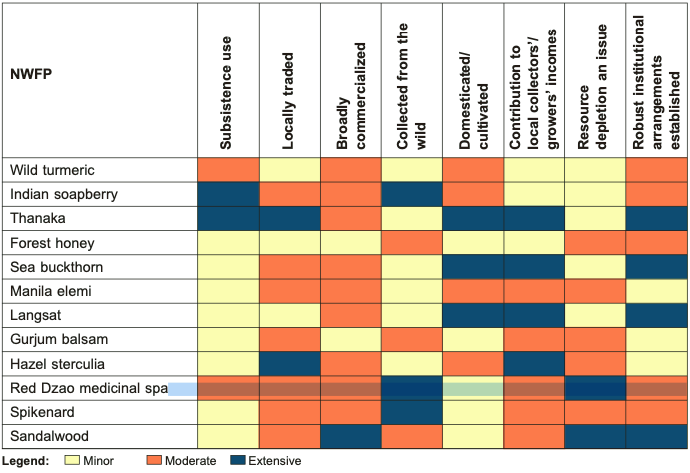

In order to tap into this market to raise the income of rural, forest communities worldwide, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations and the Non-Timber Forest Products – Exchange Programme (NTFP-EP) network examined some of the different, forest-derived beauty products, which have been used since antiquity in traditional practices and trade in various Asian and Pacific countries.

Since there was no comprehensive publication on beauty products based on forest products, although scattered information does exist, FAO and the NTFP-EP also published Naturally Beautiful: Cosmetic and Beauty Products from Forests, to bring attention to the role forests play in supplying beauty products and show how these products can provide livelihood options for forest communities. The publication assesses constraints and identifies opportunities for growth, particularly for community-based enterprises.

By bringing attention to the role of forests in supplying beauty products and the connections with livelihood security and utilization of NWFPs, awareness of the importance of forests and their connection with cosmetics will be raised, the FAO stated today.

Here are five beauty products found in nature that hold great potential to support forest communities:

1) Sandalwood oil in the Asia-Pacific region

Sandalwood oil has been an extremely important source of income and trade in the Pacific for over 200 years. Sandalwood trees are found in various countries from India, Australia and Indonesia to the Pacific Island countries. Sandalwood oil is distilled from the tree’s roots, and owing to its coveted fragrance, it is added to commercial products such as soaps, candles, perfumes and incense.

Due to the overharvesting of these trees, stocks were decimated, and the sandalwood trade became almost non-existent. However, its potential for generating income is now encouraging communities to establish new sandalwood plantations in Australia and create better trade management efforts in Vanuatu. FAO is encouraging global communities to better manage and conserve sandalwood trees in order to sustainably tap into this potential income source and preserve its cultural importance.

2) Gurjum balsam resin in Cambodia

In Cambodia, resin tapped from dipterocarp trees, commonly known as gurjum balsam, is used as a clouding agent in polishes and paints or to waterproof umbrellas and baskets. It can also be processed into essential oil and is mainly used in the perfume industry. Many people from indigenous communities collect gurjum balsam resin as an important source of income.

Since 2003, illegal logging and destructive harvesting have led to a production decline. The lack of supply and general lower demand has jeopardized the resin industry in the country. FAO has offered recommendations in protecting natural resources in the Cambodian forests and sustainably reviving this resin collection activity. This includes training people to collect resin more effectively, to learn filtering techniques that will add value to the products and to collect resin in new containers to reduce impurities and increase market value.

3) Plant-based, medicinal baths in Viet Nam

In the Sapa District in northern Viet Nam, the Red Dzao people in the Ta Phin commune have a traditional practice of a medicinal bath, referred to as “Dia dao xin”. As a part of their culture, the Red Dzao people bathe using herbal plants consisting of five to ten different varieties. They boil these plants and pour this water in barrels for people to soak in. It is believed that these medicinal baths help with fatigue and blood circulation. In addition, this treatment removes dead skin and open pores.

The community offers these treatments for tourists in homestays in Ta Phin and sells packages of pre-mixed powdered ingredients to visitors and hotels. However, unsustainable harvesting of plants and exploitation by outsiders threaten their local business. A community joint-stock company was established in 2006 to address these challenges. This company model has developed certified medicinal treatments and products, creating jobs and stable income for over 100 households which also helped to unify the community.

4) Spikenard oil in Nepal

Found in the Himalayan region, the spikenard plant, also known as jatamansi in Nepal, is used to make oil that is found in products such as perfumes, lotions, anti-ageing creams, deodorants and colour cosmetics in the international beauty industry. The collection and trade of spikenard plants provide employment for the poor in rural, high-altitude areas of Nepal.

However, the spikenard plant is listed as “Critically Endangered” on the IUCN Red List. Increased demand and high economic value led to over-or improper- harvesting of immature plants. Infrastructure development and human settlement further added to the loss of the spikenard habitat. However, its socio-economic value has fostered efforts by the government and several organizations to improve resource management and regulate harvesting practices. FAO is encouraging local participation in the value chain to promote community businesses. The development of markets will also enhance the economic potential for spikenard oil.

6) Indian Soapberry

Ancient Indian texts make references to soapberries. The book Saint heritage of India relates that Hatha yoga founder Machindranath was converted under a soapberry tree sometime during the ninth to the tenth century. The Historical dictionary of ancient India and a paper titled ‘Some Notes on the History of Soap Nuts, Soap and Washermen of India between 300 and CE 1900 explain that soapberries were found even earlier.

The genus Sapindus was mentioned for the first time in Species Plantarum by Linnaeus in 1753.

The scientific name is derived from the Latin words sapo, meaning ‘soap’, and indicus, meaning ‘of India’. Soapberry powder is known in Ayurvedic medicine as the third in a family of extremely beneficial fruits, along with shikakai (Acacia concinna) and trifla.

For hundreds of years, people in India and Nepal have been doing their laundry and cleaning with soapberry. Soapberries are also referred to as washing nuts or ritha/ reetha in Hindi. They contain saponins which have the ability to clean and wash. When in contact with water, they create a mild lather, which is similar to soap.

The last few decades have witnessed radical changes in the formulation of cosmetic and personal care products by beauty companies, which are paying more and more attention to natural, organic and safety needs increasingly being demanded by consumers. Soapberry has significant potential to take advantage of these trends.

By helping communities manage forests sustainably and explore livelihood opportunities in NWFPs, FAO is helping galvanize local economies and further forest conservation efforts globally, FAO stated.

Source: the FAO News and Media office

– global bihari bureau