The Nehro river basin

Excerpted from the book Climate Resilient Socioeconomic Growth through Water Conservation: Evidence, Implications. Livelihood, Green GDP, Circular Economy: Villages in the Chambal region, by Indira Khurana, PhD. This book brings a message of hope from the Chambal villages of Rajasthan to the world – A message of climate-resilient green growth that is decentralised, equitable, regenerative and sustainable.

Excerpted from the book Climate Resilient Socioeconomic Growth through Water Conservation: Evidence, Implications. Livelihood, Green GDP, Circular Economy: Villages in the Chambal region, by Indira Khurana, PhD. This book brings a message of hope from the Chambal villages of Rajasthan to the world – A message of climate-resilient green growth that is decentralised, equitable, regenerative and sustainable.

The decentralised rainwater conservation work led by villagers in the Nehro river basin and surrounding areas exemplifies how targeted water management strategies can turn struggling ecosystems into resilient landscapes. The restoration of the Nehro River Basin is more than just an environmental success — it is a model of how dedicated efforts can foster long-term ecological balance, community well-being, and climate resilience across regions prone to water scarcity.

The Nehro river is in the Alampur valley of the Karauli district, Rajasthan. As it flows through rocky terrain, this 29-kilometer-long river supports several villages’ agricultural activities and ecosystems, including Kaurapura, Singanpur, Alampur, and Bhojpur. Its 78-square-kilometer catchment area plays a crucial role in collecting runoff during the rainy season, contributing to the water supply in this semi-arid zone.

Also read: The Chambal Civilisation – 5: The broken grounds of Dang

One rivulet of the Nehro originates one kilometre north of Masalpur village of Masalpur block and flows in the northerly direction. Another rivulet originates from the eastern side of Babu ka Pura village, which lies in the northwest side of Masalpur village. This flows in the south-east direction, passing Unchagaon village, flowing towards the northern part of Masalpur village and then merges with the first rivulet originating one km north of Masalpur and flows northwards.

As the river continues to flow, before it passes close to Bhojpur village, water flowing from the Timangarh ka talaab also joins her. Subsequently, rivulets from Kanchanpur, Sardar ka Pura, Tarehatti, Alampur and Umari join the river, after which it flows close to or through Singanpur, Jamoora, Cheelpura, Timkoli and Kaurapura, and then flows into the Baretha jheel, after which it is known as the Kakund river. This river, in turn, then flows by the Mandapura village and merges with the Gambhir river. The Gambhir flows into the Utangan river, which flows into the Yamuna.

The river’s water availability is due to the construction of rainwater harvesting (RWH) structures. From 2000 to 2024, Tarun Bharat Sangh has worked to enhance water security along the Nehro river by constructing 15 rainwater harvesting (RWH) structures. These structures – ranging from ponds to anicuts – are strategically distributed along the river’s course to capture and store rainwater and to facilitate recharge.

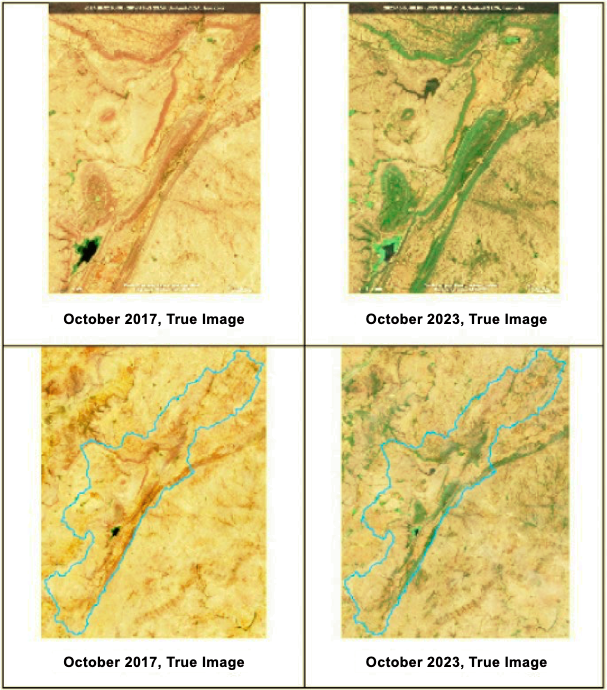

The satellite imagery comparison from October 22, 2017, and October 6, 2023, reveals significant ecological improvements, which can be explained more clearly through data analysis. In 2017, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), which measures vegetation health, was low, ranging from 0.1 to 0.3, indicating sparse and stressed vegetation. By 2023, the NDVI values have improved significantly, potentially reaching 0.4 to 0.7, reflecting healthy and flourishing plant life along the river basin and agricultural fields. The waterbodies visible in both images further underline this transformation. In 2017, the smaller waterbodies likely covered only 30-40% of their capacity, while in 2023, their expanded surface area suggests an increase of up to 60- 80%, indicative of better water retention.

Ecosystem rejuvenation is evidenced by local community reports, indicating that flow has resumed in the stream. Observations from the ground show a consistent flow of approximately 2 to 4 inches in diameter in the rivulet, which may not be captured through remote sensing data. This highlights the importance of integrating community observations with remote sensing analysis for a comprehensive assessment of hydrological changes.

Agricultural productivity has increased. In 2017, the fields were largely barren, suggesting limited irrigation and poor crop yields. By 2023, the spread of green fields suggests improved agricultural output, possibly due to more water management practices.

These improvements are likely a result of deliberate water conservation efforts. The expansion of waterbodies and the visible increase in vegetation along the river basin suggests that the construction or renovation of water structures, such as earthen dams, small ponds, has helped recharge groundwater and improve water availability.

The rejuvenation of the Nehro river basin stands testament to the profound impact that thoughtful water management and community-led efforts can have on a landscape. The geospatial distribution of the RWH structures is deliberate and thoughtful and concentrated in critical villages like Kaurapura in the north and Alampur, Timangarah, and Bhojpur further south. This widespread placement ensures maximum coverage along the length of the river, optimising rainwater capture and helping mitigate the effects of water scarcity in the area. By integrating traditional knowledge with modern techniques, not only have these waterbodies been revived but have also empowered local communities to steward their environment sustainably.

In a region where water scarcity once threatened agricultural productivity and the livelihoods of local communities, this community-led intervention supported by Tarun Bharat Sangh has transformed the basin into a thriving example of ecological restoration and resilience.

To continue…

*Indira Khurana, PhD is Chief Advisor of Tarun Bharat Sangh, an NGO working since 1975 towards climate change mitigation and adaptation by promoting water conservation, sustainable agriculture and rural development in the arid and semi-arid regions of India.