Spirituality: Surrender ego and demands

By Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati*

Na Me Bhaktaḥ Praṇaśyati – 15

Surrender is a vital aspect of bhakti. Īśvara is omniscient. He is not only omniscient but benevolent as well. He knows what is right for me. With my limited intellect, I tend to decide what is right for me and demand that what I want should be done. But as a devotee, I know that īśvara is omniscient and therefore what īśvara considers right must be right. This relieves me from much anxiety. It is a practical and good policy. When things don’t go how we want, we constantly react, resist, reject, struggle, and fight. As a devotee, we surrender.

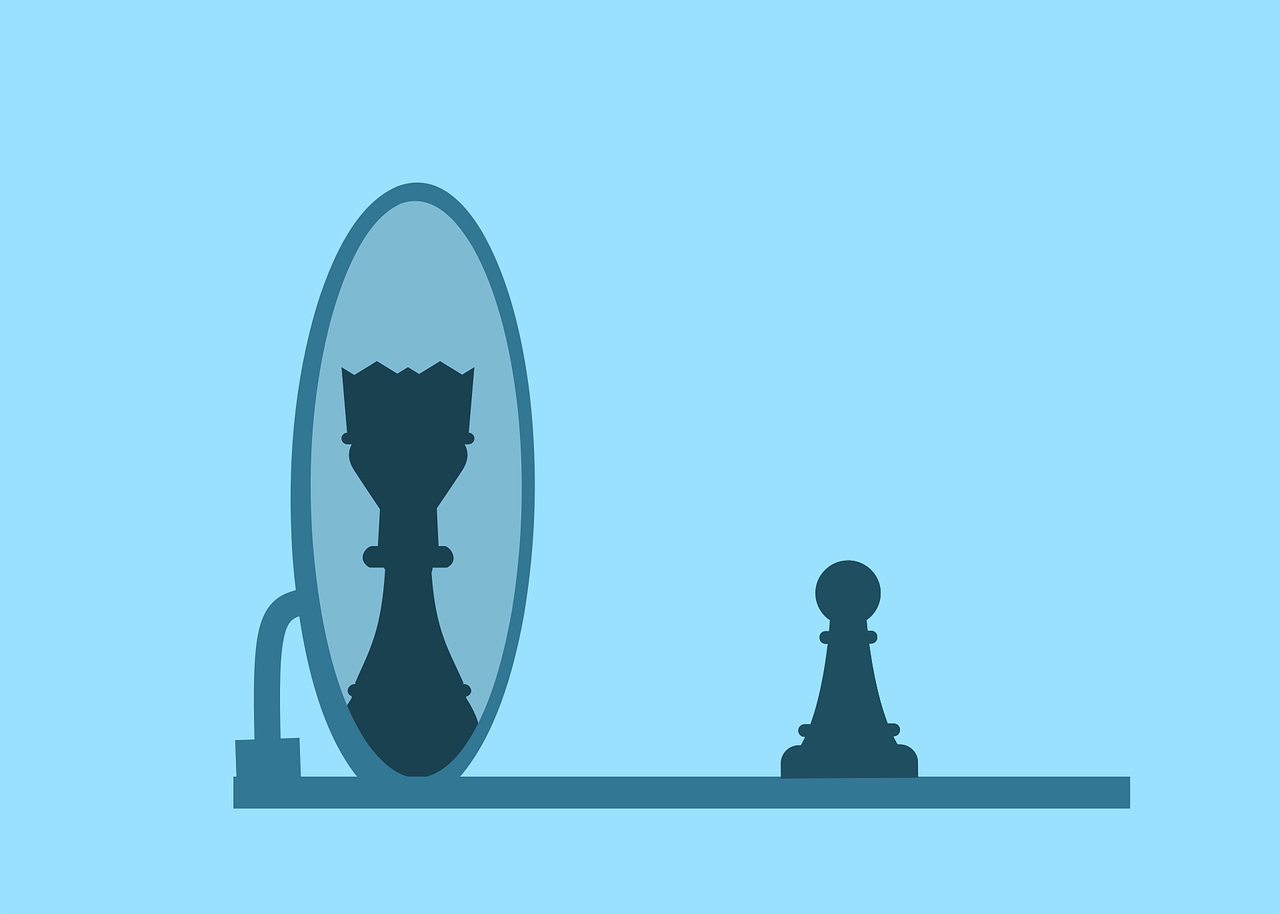

Surrendering might not sound good to you. The ego will ask questions like, “If I surrender then how will I progress? How will I grow?” These questions arise from a lack of thinking. Why do you want to progress? Why do you want to grow? “Because then I will be happy.” But you are already happy. Freedom is surrendering ego and demands. When you’re surrendering like this, there is no resistance; there is no conflict; then you are happy. It is a good policy for being happy, but it is not easy. All this is not easy because we are habituated to react.

I was recently told that it takes 26 days to change a habit. But to correct a habit, not just change it, might take a whole lifetime. If we are habituated to react in a certain way, to change that will take a long time. This is not easy, but there is no other way of being happy. There is no way that we can expect to be happy by self-promotion and gratifying the ego, who I think is my friend. The ego is my enemy, not my friend. The more I satisfy the ego and the more I gratify it, the more demanding it becomes and the more it becomes a burden. Freedom means freedom from this ego, which always wants to use free will to serve its insecurity and satisfy its rāga-dveṣas.

Surrendering ego and rāga-dveṣas is submitting to the will of īśvara. What makes me resist is either ego or rāga-dveṣas, attachments and aversions. Rāga-dveṣas create a distance between myself and īśvara. Īśvara is myself; there is no distance between him and myself. We should not have to do anything, but the problem is that some kind of artificial distance is created by ignorance, which gives rise to ego, the sense of individuality. Ego in turn gives rise to the rāgas and dveṣas, which give rise to demands and expectations and insistence that a given thing should be this way and not that way. One person’s demands and expectations clash with other people’s demands and expectations. That is how life goes on. The closer you are, the more conflicts arise.

These days everybody wants to assert their freedom. We think that asserting freedom means asserting my rāga-dveṣas. Two persons asserting their rāga-dveṣas creates a miserable situation. That is how life is; we learn to always justify our ego and rāga-dveṣas. How do we unlearn that? By submitting to the will of īśvara. We submit our rāga-dveṣas to īśvara. We submit our demands to īśvara. We submit our expectations to īśvara. We ask īśvara to now manage our life. That is what Arjuna did.

Make īśvara the manager of your life

When Arjuna chose Lord Krishna to be on his side, Arjuna requested Lord Krishna to become his charioteer. The charioteer is the driver, who manages the chariot. Make the Lord your charioteer. Make īśvara the manager of your life. Then you don’t have to worry; he will take care of it.

When you make īśvara the manager of your life, īśvara is the driver. You cannot drive the driver, and yet we have this tendency to try. We call it being a “back-seat driver.” The driver takes a route and you say, “No, go this way.” Īśvara is our driver, yet we keep trying to drive him. We keep saying, “Give me this; don’t give me that. Do this; don’t do that.” Stop driving the driver; let him drive. He knows what is right.

Now you might wonder, “How do I know he will drive correctly?” That is a matter of trusting that he is īśvara and he is your well-wisher. Trust not only that he knows what he is doing, but also that he wishes you well. Bhakti presupposes this śraddhā, trust. Otherwise, if you don’t believe or trust in God, there is no way you can take his help.

The bhakta intelligently hands over all responsibilities to īśvara. By surrendering, you are making him the manager of your life. This is the intelligent way of living. You just let him drive and do not drive the driver. Allowing the driver to drive is called bhakti; it is called surrendering. Otherwise, it’s like ignoring the GPS and going another way. How will you reach the destination? The GPS keeps saying “turn around.” Īśvara is the GPS. He knows what he is doing.

All of this is easier said than done; that is true. That is because of our ingrained habit of having our own way. We are accustomed to having happiness only when we have our way. If we develop a new habit of being happy with īśvara’s way, then we are always happy. If we can be happy only when we have our own way, then we can only be happy now and then, because often we do not have our way. Not only that but when we start having our way, we want to have our way all the time. Our demands keep growing and growing.

The bhakta is a relieved person. He has handed over all responsibility. That is called surrender, which comes from understanding and not out of helplessness. Don’t think that the bhakta is helpless. He is intelligent. Out of understanding, he knows how he should live life. What will happen to him? Na me bhaktaḥ praṇaśyati. The Lord says, mā sucaḥ, don’t grieve, don’t worry. When I take care of your chariot, trust me that I will take you to your destination.

Trusting in īśvara is intelligent surrender

Na me bhaktaḥ praṇaśyati. My devotee never suffers destruction, meaning that my devotee never suffers a loss, and never declines. He never falls from his path. He always proceeds in the direction of the destination. Sometimes the GPS seems to be taking you in a way that you are sure is incorrect. But the GPS is smarter than us. The GPS senses where the traffic is blocked and takes you through a different route. If you have trust, you will go along with it.

That happened to me once. The GPS told me to take a surface street instead of a highway. I thought, “The highway is a quicker road; why is it asking me to take this street?” I went a few miles on the highway and found that everything was blocked completely. The GPS knew that the traffic was blocked a few miles down the road, but I could not see it. Then I had to apologize for being late because I did not trust the GPS.

Similarly, bhakti involves an implicit trust, śraddhā, in īśvara. It is intelligent surrender. Śraddhā and surrender come from an understanding that īśvara is pūrṇa, complete. In pūrṇa, there cannot be any lack or want and therefore īśvara doesn’t have any agenda; whatever he does, it must be done for others. If I have my personal agenda, then whatever I do is done for fulfilling my agenda. If I have nothing to do that is for me, then whatever I do will be done as an offering.

For a wise person, there is no desire, which means that there is no agenda left, no demand left. He is atmanyevātmanā tuṣṭaḥ, satisfied with himself by himself. All satisfaction comes from his own self. Therefore, he has no need or expectation of getting satisfaction from somewhere else.

All our demands are basically seeking satisfaction from the world. When you tell me to sit down here, you are saying, “Please make me happy by doing that.” If I don’t sit down, you get upset and if I sit down, you are happy. Behind all our demands and expectations, there is only one demand. We want the world to make us happy. But as we have seen, that is a losing game. The world does not make us happy all the time.

Therefore, the secret to happiness is to discover happiness in ourselves. If we discover happiness in ourselves, then there is no need to make demands and seek happiness from elsewhere.

…to be continued

*Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati has been teaching Vedānta Prasthānatrayī and Prakaraṇagranthas for the last 40 years in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. Throughout the year, he conducts daily Vedānta discourses, accompanied by retreats, and Jñāna Yajñas on Vedānta in different cities in India and foreign countries.