Spiritual Discourses: Surrender and Inner Freedom

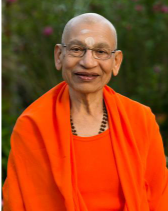

By Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati*

Freedom is very dear to us. Each one of us wants to be free. We have a natural love for freedom for the simple reason that freedom is our nature. There is an innate love for one’s own nature. Therefore, the love for freedom and happiness is natural. Unfortunately, we find ourselves to be not free but bound. We find ourselves limited in many ways and cannot accept our limitations, because limitation is also not our nature. Hence, there is resistance, a non-acceptance of any limitation.

We appear to be limited

We find ourselves to be limited and bound by many laws. Very often, we find that we are not able to do what we want and are required to do many things that we do not care to do. For example, you may want to drive your car at 120 miles per hour on a road where the speed limit is 65 miles per hour. You may start speeding, but you slow down when you find others suddenly obeying traffic rules and slowing down because of a patrolman nearby. Even when you are speeding, there is fear because there is a law and you find yourself flouting the law. It seems like there are laws everywhere and in every field of life. For instance, there are laws that are evident at the dining table every day. These are the laws that determine what we should eat or not eat. Very often, we are obliged not to eat what we like to eat because we are told that what we like is not good for us. Then again, we like to sleep late, but we are told that it is not good for us; instead, we are expected to wake up early, meditate, and exercise. We find that we are constantly required to do what we do not care to do, and are restricted from doing what we would rather do. There seems to be a tremendous restriction on our freedom.

We find that we are limited in terms of time, place, and attributes. We know that we were born and that someday we will die. We do not like that; we do not want to die. When a person seems to want to die, it is because of some difficulty he cannot overcome. There may be physical pain or some other insurmountable problem in life. If you remove those problems, that person will not want to die. Nobody wants to die. It is only out of helplessness that a person may say that he wants to die. Death is contrary to our nature. We find ourselves to be mortal and do not like any of the messengers of death like old age, diseases, etc. That is why there is a fascination for heaven where it is said that the devatäs or gods, the denizens of heaven, always remain young. They do not suffer old age or death. We generally associate old age with helplessness and proximity to death. That is why etiquette demands that we not ask a person his or her age. Nobody wants to grow old. These are some realities of life, which we call laws. There seems to be resistance towards these realities in the mind.

We are limited in place. The limitation is that we can be in only one place at a given time. Very often, we wish to do many things at the same time. It would be nice if we could be here at the Gurukulam and also elsewhere. But that is not possible; in order to be in one place, we have to give up the benefits of being in a different place. Sometimes, we feel guilty that we are in one place and not at some other place where we should be. Therefore, we are aware that we are limited in terms of place.

Being limited in our capacities is another limitation we experience. Many capacities are given to us: Jnana Shakti or the capacity to know, Ichha Shakti or the capacity to desire or to will, and Kriya Shakti or the capacity to act. However, these capacities are also limited. We find ourselves limited with reference to knowledge, regardless of how much we know. Even if we read the entire newspaper, we can never know everything that is happening in the world. Often, we find that other people know more than we do in every subject. We also feel limited in terms of our abilities to act because our skills are limited. While we enjoy the power to know, to will, and to act, it is limited in scope. We are not happy with our limited capacities.

There would be nothing wrong with limitation if we were comfortable with the fact that we feel limited, bound or controlled. Vedanta would then not be necessary. For instance, Vedanta is not necessary for animals because they seem to be comfortable being what they are. We human beings, however, need Vedanta because we are not comfortable with our sense of limitation or bondage and are constantly seeking freedom from it. Once we understand the nature of this bondage, we will understand the nature of freedom and see how surrender can become the means to freedom.

Our sense of limitation arises from ignorance

Is this bondage a reality about us? Are we really limited or bound? Or do we merely feel that we are limited and bound? The answer is that our sense of limitation and bondage is not a reality about us. It is a notion, which has arisen because of a certain perception we have of ourselves. The perception is that we are this body, mind, and intellect. Our identification with the body, mind, and intellect gives rise to the perception that we are the ego, the individual being. Vedanta teaches us that this perception is not a fact. The body we are not; the mind we are not, and the intellect we are not. We possess them, but these are only the means that are given to us in order that we may live our lives and grow and be happy; we are not them. However, we do not know this and take the body-mind complex to be the true self. In Vedanta, this is called adhyäsa, superimposition. We are born with this adhyäsa, which is a product of ignorance. We are born ignorant. This ignorance is not merely an absence of knowledge; it also creates false notions or false understanding.

In Vedanta, the example of the rope-snake is given to illustrate the idea of false notions. It shows how, in inadequate light, a piece of rope can be mistaken for a snake. Seeing a snake where, in fact, there is a rope is called adhyäsa or the superimposition of the snake upon the rope. In this, we take one thing to be something else. The snake is not a reality. It is a notion because the snake exists only in the mind as a projection; it is a subjective perception. However, the perceived snake remains a reality to the one who does not know that it is false or that it is a delusion. He does not know the reality of the rope. The false perception even evokes reactions such as fear; what becomes important is not what it is, but what it is perceived to be. Similarly, we have false perceptions or notions about the self.

Ignorance creates false perceptions

The notion we have about ourselves is that we are bound and limited beings subject to birth, growth, old age, and death. We imagine that we are limited in time, place, and attributes. Is this the truth? Do we perceive ourselves as we truly are? Vedanta teaches that our perception of ourselves is incorrect: our true nature is wholeness, yet we see ourselves as being incomplete; our true nature is freedom, yet we see ourselves as being bound; our true nature is all-knowledge, yet we see ourselves as being ignorant, and our true nature is immortality, yet we see ourselves as mortal beings. Our perception of ourselves is thus totally contrary to our true nature due to our ignorance. It is this ignorance, which brings about false knowledge and false perception.

In the rope-snake example, there is not only ignorance of the rope but also the false perception of a snake.

Similarly, in our case, there is not only ignorance of our true nature but also the false perception that we are incomplete, helpless, limited, and bound. We are born with these false perceptions. We have had this perception about ourselves from beginning-less time, in the perpetual cycle of birth and death. There is thus no answer to the question as to when this ignorance actually began; this is how it is.

There is no beginning of ignorance and, therefore, there is no beginning of false perception. There has never been a time when we have known ourselves as we truly are. We have always taken ourselves to be limited beings and have been trying to become free from this sense of limitation.

False perceptions lead to attachments and aversions

We find ourselves to be insignificant beings trying to become significant. Even if one is a king, and worshipped in his own kingdom, the fact remains that nobody knows him outside his kingdom. One may be a great person in his own home, but the street dogs bark at him when he walks out of the home! The moment we begin to think we are somebody, something or the other happens to make us feel insignificant again. We do not like insignificance and cannot deal with it. Our lives are nothing but a struggle to prove to the world that we are something or somebody.

Vedanta tells us that all this suffering and sorrow has its roots in our false assumptions of being limited and bound. Nothing in the world can make us sad or unhappy if we did not have this false perception of ourselves. If we understand our true nature, there would be no cause for unhappiness. As Lord Krishna says in the Bhagavad Gita [2-11]:

अशोच्यानन्वशोचस्त्वं प्रज्ञावादांश्च भाषसे |

गतासूनगतासूंश्च नानुशोचन्ति पण्डिता: ||

You grieve for those who should not be grieved for. Yet you speak words of wisdom. The wise do not grieve for those who are living or for those who are no longer living.

Whenever we grieve, it is for ourselves that we grieve. Grief or unhappiness always pertains to us, although we may think that it is because of something that has happened to somebody else. Sorrow is always centred upon the self, even though we feel that someone else is the cause of our sorrow, and therefore, we try to correct or change the world around us so that we can become free from sorrow. As Pujya Swami Dayanandaji would say, “I am the problem, and I am the solution.” Which ‘I’ is the problem? The ‘I’ that has the wrong perception of itself is the problem.

Our perception is that we are needy. If our needs are fulfilled, we find ourselves to be happy and, if they are not, we are unhappy. Whether or not we are happy or comfortable is determined by the world around us. If it obliges us by fulfilling our needs, we are happy. The world becomes important to us because we seek happiness and security from the world. The world may not necessarily be a kind and supportive place. There cannot be kindness where there is competition; for every winner, there are many losers. Thus, we are not free to decide whether we are happy or unhappy. If being happy were in our hands, we would never be unhappy. Nobody wants unhappiness. Right now, we do not determine whether we are happy or not; we let the world determine that. If the world is kind and obliging, we are happy; if not, we are unhappy. Thus, we find ourselves to be dependent and helpless.

We seek comfort from certain happenings or outcomes. When there is an apprehension that they may turn out differently, there is fear and insecurity. If we have no fear or insecurity, the outcomes would not matter. In that case, we would be free to do what we want. All our unhappiness, sadness or sorrow is caused by our own false perceptions of ourselves. Understanding this clearly solves half the problems in life. We would then not blame the world for what happens to us; knowing that it is we who empower the world to make us sad or happy, we would not react to whatever happens to us. If we do not empower them, nobody can do anything to us. The world tightens our ‘screws’ because the ‘threads’ are there. This is the cause for sorrow. If these threads of false perceptions and complexes born of these perceptions were worn out, the screws would not matter.

How do our false perceptions of ourselves bring about a false perception of the world? We perceive ourselves to be limited and, therefore, we feel insecure. This personal insecurity determines how we view the world. Some people and situations appear to be kind, helping, supportive, and conducive to our security and we look upon them as desirable. What one really desires is one’s freedom, security, and happiness, and, therefore, anything that one views as a means to this freedom, security, and happiness becomes desirable. Conversely, whatever one perceives as a threat to one’s freedom, security, and happiness becomes undesirable. We feel the need to defend and protect ourselves from such perceived threats. The ignorance that results in false perception also creates these ideas of desirability and undesirability. Therefore, we divide the world into that which is desirable and that which is undesirable.

Every source of happiness is important to us. We want to hold on to it for our comfort. This kind of relationship is called attachment. Whatever is considered desirable causes attachment. It is a relationship of dependence; in its presence, we feel happy and, in its absence, we feel insecure. For example, a little child feels secure in the presence of their mother and insecure without her. Attachment and aversion are bound to be there with respect to the world when there is a false perception about oneself. Nobody is free from that.

Lord Krishna says in the Bhagavad Gita [3-34]:

इन्द्रियस्येन्द्रियस्यार्थे रागद्वेषौ व्यवस्थितौ |

तयोर्न वशमागच्छेत् तौ ह्यस्य परिपन्थिनौ ||

There is attachment and aversion with reference to every sense object. May one not come under the spell of these two because they are one’s enemies.

From the time of our birth, we have tendencies of attachment and aversion arising from our needs and insecurities. We are not comfortable with ourselves since we cannot will to be comfortable, happy or secure. That seems to depend upon things other than us.

We have a particular perception of the world arising from our own tendencies of raga and dvesha, attachment and aversion, and cannot help but judge every person, object, and situation. Therefore, we judge things as desirable or undesirable and interact with the person, object or situation accordingly.

Rather than being deliberate, our interaction with the world is often a reaction. We are given free will, yet it is not very often that we are able to use that free will. It is not very often that our actions are deliberate. More often than not, our actions are determined by our attachments and aversions. Thus, we live in our own private worlds of likes and dislikes. We do not interact with the world as it is; we create a world of our own perceptions. Understanding the realities of the self and the world will enable us to drop our false perceptions about ourselves and of the world.

The true perception of the self leads to inner freedom

Vedanta teaches that the feeling of dependence and insecurity is not a reality about us. If we were to analyze a moment of happiness, we would find that at that moment our false perception of ourselves has dropped off momentarily, and we have come face to face with the true self. To the extent that we find this true self, we are happy. Happiness is indeed our true nature. It is the unhappiness arising from the false notion of ourselves that inhibits the expression of this happiness. This false notion should be dispelled. Happiness is not something that is to be acquired. If we understand the nature of happiness and freedom, which we do experience occasionally, we will come to realize that the external objects, situations or persons who appear to cause happiness are simply instrumental in helping us gain a glimpse of our own selves. They help us experience the true self that is hidden behind the cloud of insecurities etc. Happiness is the result of our true perception of ourselves. If this is clear, most problems will be solved. The only cause of unhappiness, insecurity, limitation, bondage, non-acceptance, or dissatisfaction is a false perception. One’s true nature is quite contrary to what we take it to be.

To achieve freedom or happiness, one has to get rid of this false perception of oneself. It is done in two steps. The first step is to understand the realities of life, the world, and God, and, the second step is to gracefully accept these realities. How we perceive ourselves affects our perception of everything else; a distorted perception of oneself will only provide a distorted perception of the world and of God.

…to be continued

*Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati has been teaching Vedānta Prasthānatrayī and Prakaraṇagranthas for the last 40 years in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. Throughout the year, he conducts daily Vedānta discourses, accompanied by retreats, and Jñāna Yajñas on Vedānta in different cities in India and in foreign countries.