[the_ad_placement id=”adsense-in-feed”]

Exclusive on World Poetry Day

On the World Poetry Day 2020, poet and Ambassador Abhay K. shares his efforts to take Indian Poetry written in various languages of India to the World.

-Abhay K.*

-Abhay K.*

On 10 December 1950, William Faulkner began his Nobel Prize acceptance speech with these words, ‘I feel that this award was not made to me as a man, but to my work – a life’s work in the agony and

sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit…’

As art transcends the artist, poetry transcends the poet. Faulkner further

elaborated upon the importance of artwork over the artist in an interview with The Paris Review in 1956. Referring to the futility of conflict over the authorship of Shakespeare’s works, he contends, ‘…what is important is Hamlet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, not who wrote them, but that somebody did. The artist is of no importance. Only what he creates is important.’

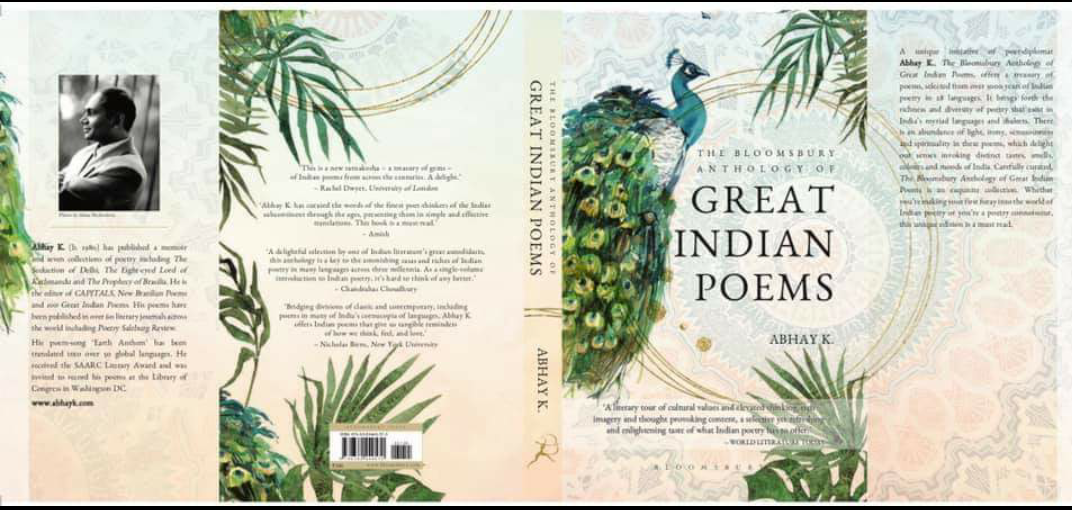

This is what I had in mind when I started editing 100 Great Indian Poems and its companion volume 100 More Great Indian Poems, which combined together make The Bloomsbury Anthology of Great Indian Poems. The poetry anthologies I had come across while growing up in India had a clear emphasis on ‘the poets,’ which is illustrated in the titles such as Ten Twentieth Century Indian Poets, Twelve Modern Indian Poets, Nine Indian Women Poets or 60 Indian Poets. An exception maybe These My Words, edited by Eunice de Souza and Melanie Silgardo, which could be otherwise daunting and inaccessible to common people. These lines from De Souza’s poem ‘Meeting Poets’ are telling –

I am disconcerted sometimes

by the colour of their socks

the suspicion of a wig

the wasp in the voice

and an air, sometimes, of dankness.

Best to meet in poems:

cool speckled shells

in which one hears

a sad but distant sea

[the_ad_placement id=”content-placement-after-3rd-paragraph”]

A general reader does not need to know which prizes a poet has won, how many books has s/he published or which festivals has s/he attended; the charm and force of an individual poem is sufficient to move the reader. Poetry survives the poets because of its timeless and intrinsic value. Therefore, I don’t understand the obsession of the 20th century anthologists of Indian poetry with the poets.

I was fascinated withRashmirathi by Ramdhari Singh Dinkar while growing up as a child in rural Bihar. I chanced upon my father’s worn-out copy of this book at home when I was in class four. The magic that I had felt in the sound and energy of words in Rashmirathi stays with me till date. This Hindi epic tells the story of Karna, Krishna, Pandavas and Kauravas. It was my first lesson in literature as well as in politics and diplomacy. I memorized its third canto by heart as I often read it. I still do. I have unsuccessfully tried to translate this work into English. The magic of native words is lost in translation; and therefore, verses from Rashmirathi do not find a place in the anthology of great Indian poems. For the similar reason of untranslatability, several other great poems could not fit into this anthology.

My desire to take rasa and riches of Indian poetry to the world and to bring the focus back to the poem from the poet gave birth to 100 Great Indian Poems. This was called for after having brought some of the world’s best poems to India in CAPITALS in 2017. It received overwhelming reception in India and abroad. Its first volume sold out within first few months of its publication.

Commenting on the selection of poems in 100 Great Indian Poems, French philosopher Christopher Macann said, ‘they are quintessential, always simple, often profound, generously sensuous, occasionally political and frequently funny.’ Reviewing the anthology in the First Post, Manik Sharma wrote, ‘100 Great Indian Poems attempts something endearingly unique and preposterously impossible—to merge and collate 3000 years of Indian poetry’s history via a hundred of its samplings…’

100 Great Indian Poems has been translated into Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, Irish, Russian, French, Malagasy and Nepali. The Portuguese edition is published by the University of São Paulo, Brazil, the Spanish edition by the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, Monterrey, Mexico while its Italian edition is published by Edizione Efesto in Rome, Italy. It is for the first time that a poetry anthology from so many Indian languages covering over three thousand years of Indian poetry has been translated and published into several world languages.

The overwhelming interest of translators and readers inspired me to come up with 100 More Great Indian Poems to serve as its companion volume, and the growing demand for both these anthologies inspired me to bring out a combined volume titled as The Bloomsbury Anthology of Great Indian Poems.

India has a plethora of languages and each language’s rich nuance is tapped in poems waiting to be discovered, read, discussed and cherished. How does one put together an anthology of poems from so many Indian languages? How does one introduce the gems of Indian poetry to the world?

India’s regional languages have a wealth of great Indian poems which rarely comes out in the absence of good translations. Every poem included in this anthology speaks out loud—we need more translations and translators. Most of the translators in this anthology are poets themselves, who carry not only a poetic but also linguistic sensitivity, the prerequisite for rendering these poems from India’s regional languages effectively into English. This anthology also highlights the achievements of Indian poetry written in English by Indian poets as well as Indian diaspora poets and how they have turned English, once a foreign language, into their own.

Editing this anthology has been a labour of love. I have read widely, almost all poetry anthologies covering different languages and geographical regions of India published so far. It includes poems translated from twenty-eight Indian languages, viz., Assamese, Bengali, Bhili, Chakma, Dogri, Gondi, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Khasi, Kokborok, Konkani, Maithili, Malayalam, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya, Persian, Punjabi, Rajasthani, Sanskrit, Santhali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu and Prakrit languages including Pali as well as poems originally written in English.

There is an abundance of light, irony, sensuousness and spirituality in the poems. But, what makes a poem an Indian poem? How is it different from an African or a Latin American poem? I think it is the smorgasbord of sensibilities, landscapes, customs, rituals and mythologies these poems concoct and offer, which are uniquely Indian in some way or the other. The canvas of this collection covers over 3000 years of Indian poetry.

Interestingly, along with many well-known names, some poets whose

poems are included in the anthology are virtually unknown even in poetry circles. Poems included in this anthology have shades of all rasas (which roughly translates as flavours) including erotic, comic, heroic, horrific among other strains and cover almost all traditions of Indian poetry including bhakti poetry. The distinctive voices of the tribal, dalit, feminist and LGBT communities also find space in this collection.

What makes a poem great? Is there a standard definition of a great poem? I have a simple answer to this question. What moves me is great for me. What moves you is great for you. It could be a painting, a piece of music, a photograph, a poem or anything under the sun. I don’t think there is or there can be a universal definition of greatness. Even Buddha, the enlightened one, advised his followers not to believe what he said without verifying it themselves, not to take his path but to find one’s own. In a similar vein, I would suggest you find your own great poems. Make your own anthologies of great Indian poems.

This anthology opens with an ancient verse by poet Bhavabhuti, which, looking over its shoulder, remembers the achievements of past masters but not without offering homage to the language – the vehicle of poetic spirit all over the world. May poetry live on, and myriad languages thrive in our troubled world!

The poems in this collection are arranged in alphabetical order of their respective titles instead of the chronological dates of their publication, so as to underline the timeless nature of great poetry.

With this anthology I hope to introduce you to the rich world of Indian poetry offering the distinct tastes, smells, colours and moods of a unique and ancient civilization. I read these poems again and again, in times of joy and sorrow; and while reading these, I enter into a world of bliss. I wish you too an unforgettable journey with these

great Indian poems.

*Bihar-born Abhay K. is an eminent poet and winner of SAARC Literary Award and Asia-Pacific Excellence Award. At.present he is serving as Indian Ambassador in Madagascar.

Some Poems by poets from Bihar included in The Bloomsbury Anthology of Great Indian Poems

MAKING LOVE TO HER

– Dharmakirti

Making love to her lasts only moments

like a dream, illusion, ending in regret

I reflect upon this truth a hundred times

Yet my heart can’t forget the gazelle-eyed girl.

Translated from Sanskrit by Abhay K.

TOMORROW

– Vidyapati

He promised he’d return tomorrow.

And I wrote everywhere on my floor:

“Tomorrow.”

The morning broke, when they all asked:

Now tell us, when will your “Tomorrow” come?

Tomorrow, Tomorrow, where are you?

I cried and cried, but my Tomorrow never returned!

Vidyapati says: O listen, dear!

Your Tomorrow became a today

with other women.

Translated from Maithali by Azfar Hussain

FAMINE AND AFTER

– Nagarjuna

For days and days the hearth stayed cold, the hand mill quiet

For days and days the one-eyed bitch slept nearby

For days and days lizards paced on the wall

For days and days rats too were miserable

Grain came to the house after many a day

Smoke rose above the courtyard after many a day

The eyes of the household shone after many a day

The crow scratched its feathers after many a day.

Translated from Hindi by Nalini Taneja

THE DOOR

– Anamika

I was a door

The harder they beat me

the wider I opened

They walked in and saw

a great cosmic whirling

When the grinding stops, the spinning begins

When the spinning stops, the sewing begins

Something or other, all day, non-stop

And in the end my broom sweeps it all up

sweeps up the stars in the sky

mountains, trees, stones

all the shards and splinters of creation

and collects them in a basket

stores them somewhere

deep inside

in some corner of the mind.

Translated from Hindi by Ritu Menon

GIRLS ON ROOFTOPS

– Alok Dhanwa

Still the girls come on to the rooftops

Their shadows fall on my life

The girls are here for the boys

Downstairs, amidst bullets, the boys play cards

Sitting, on the stairs above the drain

Lazing on benches outside the footpath tea-stall

Sipping tea

Around a boy who plays the mouth-organ sweet

Timeless tunes of Awara, Sree 420.

A newspaperwallah spreads his wares

And some young men read the early edition

Not all are students

Some unemployed yet, small timers some

Whilers, lumpens

But in their veins, bloodstreams

They await a girl

A hope—that from these houses and rooftops

One day, some day—love will arrive.

Awara, Sree 420: popular Hindi films

Newspaperwallah: Someone who delivers newspapers door to door

Translated from Hindi by the poet

[the_ad_placement id=”sidebar-feed”]