Pandemic, Trade and SDGs -4

Global Trade and SDG 2030 Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries

Economic literature supports a positive correlation between trade and reduced inequality. There are already established positive effects of trade in for both economic growth, job creation, and poverty reduction. Trade also has important implication for inequality, both within and among countries. Trade fosters economic growth in efficient reallocation of resources, exploitation of scale economies, technology exchange, raising living standards and income levels.

However, both inequality and trade have increased in many developed and developing countries since 1990 . While this trend is most evident in advanced economies, it has also occurred in developing and emerging economies across Eastern Europe, Asia, and the Middle East . Simultaneously, trade liberalisation has also increased steadily. Political tensions are arising, largely in advanced economies as trade liberalisation is blamed for a reduction in manufacturing jobs upon which poor people depend in these economies. Trade liberalisation may also represent a scapegoat for the slowed economic growth faced by advanced economies since the global financial crisis. Unfortunately, many other forces including technology, domestic policies, weakened labour protections, and lack of financial inclusion that have contributed to the increased in domestic inequality.

Also read: Pandemic, Trade and SDGs: Opening up to trade affects growth positively in a number of ways

Unfortunately, wage inequality is associated with some liberalisation episodes particularly as it is associated with a rise in the skill premium in many developing economies. Trade leads to an increase in earnings of better educated workers relative to less educated ones, especially in developing countries. The rise in skill premia may also be associated with offshoring and global value chains. As the global supply chains situate production across different countries, workers in developing countries specialise and remain in earlier stages of production. Ultimately, there is evidence of a non-monotonic effect on wage inequality.

In terms of inequality between countries the WTO remains an active partner in strengthening the multilateral trading system as an inclusive and equitable force for developing countries. This is largely through the adoption and operationalisation of over 140 Special and Differential Treatment provisions spread over expanded rules in WTO Agreements.

These special provisions are generally categorised into six types:

- Provisions aimed at increasing the trade opportunities of developing countries

- Provisions under which WTO Members should safeguard the interests of developing countries

- Flexibilities regarding commitments, actions and use of policy instruments

- Transitional time-periods

- Technical assistance

- Special provisions for Least Developed Countries (LDCs)

The inclusion of this large set of substantive provisions in WTO Agreements illustrates efforts by members to make the multilateral trading system more inclusive and equitable.

Furthermore, WTO members have also extended a transition period on trade-related investment measures for LDCs and agreed on a decision calling on Members to provide duty-free and quota-free market access for the LDCs in line with Target 10.A SDG 10 which calls for countries to implement special and differential treatment for developing and least developed countries, in particular least developed countries. This target is monitored by examining the proportion of tariff lines applied to imports from LDCs and developing countries with zero-tariff.

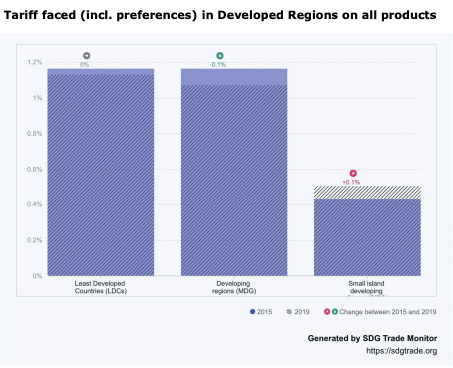

However, the timely implementation of the duty-free and quota-free market access for LDCs on a lasting basis has been slow. Between 2015 and 2019, there was no change in the level of tariff faced by LDCs products in developed regions as seen in figure 6 below. The developing region countries as a whole, only saw a 0.1% reduction in the level of tariff faced on all products exported to the developed regions. For Small Island Developing Countries (SIDs), the level of tariff faced actually increased by 0.1% between 2015 and 2019.

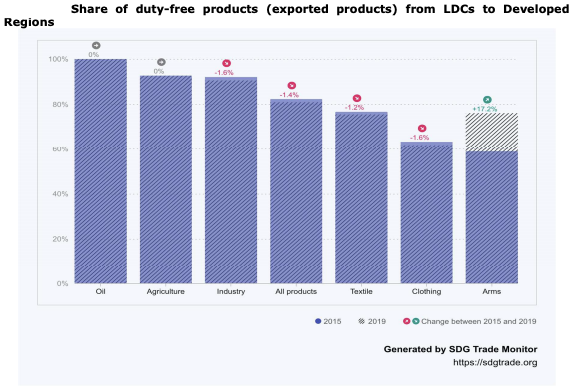

On all products from LDCs to Developed regions, the share of duty-free products has reduced by 1.4% between 2015 and 2019 . While the share duty-free agricultural exports from LDCs to Developed regions remained the same, Arms export from LDCs climbed by 17.2% between 2015 and 2019. The share of duty-free industrial, clothing, and textile exports from LDCs to Developed regions declined by 1.6% and 1.2% respectively between 2015 and 2019 as well.

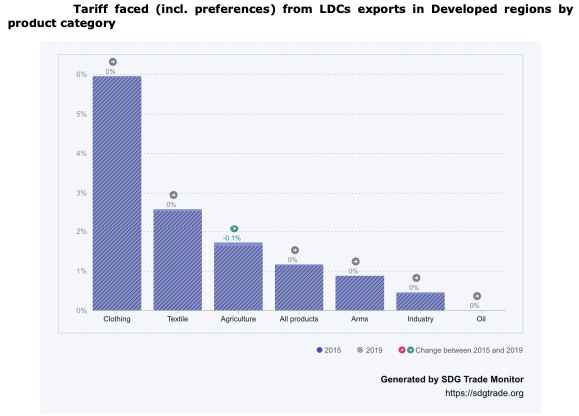

More positively, given that agriculture continues to be the mainstay of most LDCs, it is encouraging to note that the level of tariff faced by LDCs in Developed Regions on agricultural products reduced by 0.1% between 2015 and 2019 as shown in figure 8, with the level of tariffs on other products unchanged.

Improving market access for LDCs continue to remain a priority for WTO members with Montenegro and Kazakhstan extending its EAEU Duty-Free and Quota-Free (DFQF) arrangement to LDC members in 202033. Russian also stepped-up its implementation of the Nairobi Decision on Rules of Origin, which allows LDCs to use non-originating materials up to 50%, with increment up to 60% in 2025. It is equally important to note that 24 WTO members have operationalised the LDC Services Waiver, which gives preferential treatment to services, and service providers of LDCs member states.

The positive effects of trade on economic growth and poverty reduction are detailed in recent reports by the World Bank Group and World Trade Organization (2015, 2018, and 2020). These reports also note that poor people may not fully participate in the gains from trade for a variety of reasons, including both domestic and international policies. For example, research shows that industries that face higher tariffs and trade barriers in the export market pay lower wages in all countries.

Moreover, trade does involve adjustment costs. The effects of trade on the poor will depend on geography (rural versus urban areas), individual characteristics (skill, gender), type of trade policy change (increased import competition or export opportunities) and where they work (industry, firm, formal/informal sector). Economic literature suggests that many of the adverse effects of trade adjustment are a result of worker mobility costs, costs to move across sectors, regions or tasks.

It is important to note that earlier findings still stand; trade tends to raise aggregate employment and real wages in the long run. Initial reductions in employment due to trade liberalisation and competition are generally met with employment creation resulting from export opportunities, in addition to the increased consumption due to a reduced consumer price index. However, inclusive trade policies must take the specificities of the trade adjustment process and period into account.

Governments should implement early and comprehensive policy action to improve labour mobility, these are usually a combination of active and passive labour market policies. Passive labour market policies typically aim to replacement income during periods of joblessness and adjustment, such as unemployment benefit systems and social insurance programs.

Active labour market policies typically help workers find new jobs as quickly as possible and cover a wide range of policy options. A variety of theoretical research suggests that wage subsidies are the best way to compensate workers facing adjustment issues.

However, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to reduce trade-related adjustment costs. General adjustment policies, which typically involve passive and active labour market policies and well-funded social safety nets appear to be more effective than specific trade adjustment policies that focus on compensating workers in specific sectors or who have been affected by specific legislation. Geographically specific trade adjustment policies may also be necessary to integrate and reinvigorate lagging regions, especially when general social safety nets and adjustment policies prove insufficient. These may include infrastructure and transportation investments to increase labour mobility, as well as tax incentives and regulation. Furthermore, training assistance and education programs have an important role to play in adjustment policies. More generally, steps can also be taken at the multilateral level to maximise gains from trade for the poor. The multilateral trading system must address distortions in agriculture to improve market access and reduce food price volatility which can benefit both poor farmers and poor consumers, to develop inclusive and stable multinational rules for services and e-commerce trade. Policies that prioritise and develop MSMEs, improve access to trade finance, and encourage investment in developing and least developed economies will also have significant impact on the global poor.

*Excerpted from report on WTO Contribution to the 2021 High-level Political Forum

– global bihari bureau