Understanding health care global value chain and the role of multinational corporations

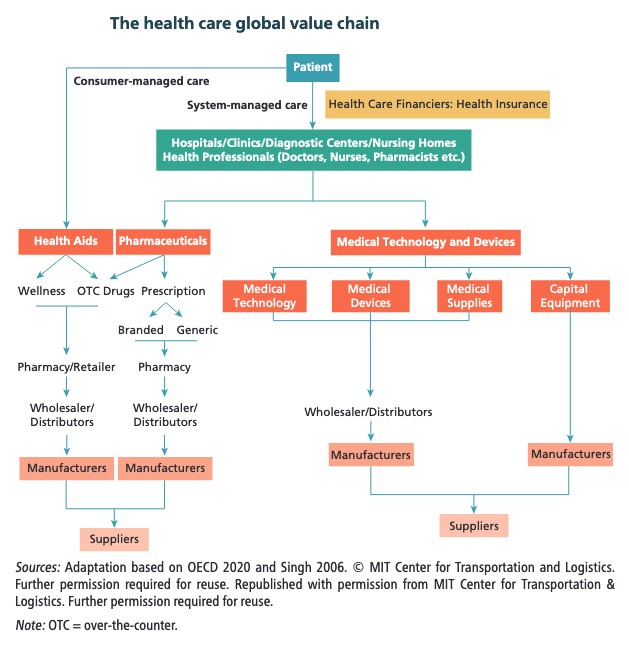

In the health care global value chain (GVC), resources, organizations, and institutions act together, primarily to improve, maintain, or restore patients’ health. It comprises both medical goods and services. The medical goods segments mainly include pharmaceuticals, medical technology, and devices. Services are primarily provided by hospitals, clinics, health professionals, diagnostic laboratories, nursing homes, and integrated delivery networks. Health insurance, logistics, and distribution services also play important roles in the value chain.

The health care value chain features complex interactions among a diverse set of stakeholders. Each stakeholder—be it a health care establishment or a medical device company—has different concerns and is driven by often divergent objectives and problems. The complexity and opacity of health care delivery is another critical factor.

Uniquely to the health care industry, the consumer, or patient, has a limited say in the choice of a product or service. Instead, the multiplicity of regulations, the number of parties involved, and the high expertise required all mean that decision-making is

widely dispersed. In addition, products and services in the health care value chain are highly customized to perfectly match needs, making it almost impossible to plan their efficient supply on a large scale.

The supply of health care often starts with hospitals and clinics, where private sector participation (measured as the share of private hospitals) varies considerably across countries—ranging from close to zero in Nordic countries to over 80 per cent in Japan, the Netherlands, and the United States. This variation is not linked to income level or stage of development: lower-middle-income countries like Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam closely follow the Nordic countries with less than 15 per cent private sector participation, whereas Cambodia, India, and Indonesia fall at the other end of the spectrum with Japan and the United States. It is also important to note that medical services are often subject to stringent regulation and limited foreign capital participation.

The manufacturing and distribution of goods and technology are dominated by private firms, especially multinational corporations (MNCs). Both the pharmaceutical and medical device segments are highly capital and innovation-intensive and face a highly regulated environment requiring extensive data collection and information exchange. Products often have high-profit margins and are sold to professionals and institutional buyers. Lead firms try to entrench their positions by

spending huge amounts on R&D and patenting, erecting high barriers to entry.

Leading pharmaceutical firms from a few high-income countries dominate brand name drugs and new drug introductions, but MNCs from middle-income countries are increasingly competitive in the generic-drug market. Many major global pharmaceutical companies were founded more than a century ago in a few high-income economies.

Whereas new introductions require massive capital investments, huge R&D efforts, a lengthy development process, and are highly unpredictable, mid-life-cycle products tend to have standard production processes, lower profit margins, and stable demand. Lead MNCs increasingly outsource production of these medicines to reduce costs, resulting in new opportunities for players from middle-income countries. For example, India has become a major provider of generic drugs globally; it was the third-largest producer of pharmaceuticals by volume in 2019 and fulfilled approximately 50 per cent of the global demand for vaccines. Many pharmaceutical companies and contract manufacturers in Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries have also internationalized and become MNCs themselves (ASEAN and UNCTAD 2019).

The medical technology and devices segment has even higher market concentration and stickier buyer-seller relationships than pharmaceuticals. Products are developed over a long period, allowing companies to benefit from time and technology accumulation. The life cycle of the product is also relatively long, and lead firms often establish long-term relationships with customers to offer training, maintenance, and aftercare services. Hospitals, doctors, and equipment manufacturers usually form a cooperative relationship. The device’s stability and reliability are extremely important, and buyers are therefore less sensitive to prices. Once customers start to use a company’s product, the switching cost is high, and the device cannot be easily replaced. Feedback from doctors and patients in turn enables manufacturers to improve the performance of their devices. These characteristics make the entry barrier extremely high in the medical device segment, so latecomers have trouble competing with established firms.

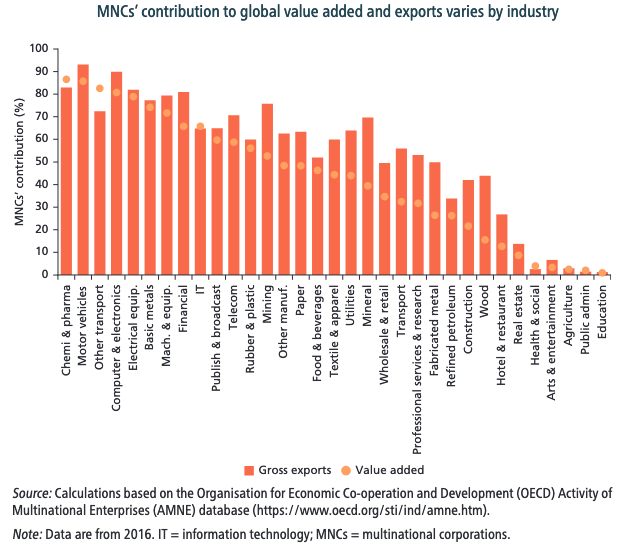

MNCs play a dominant role in health GVCs, though it varies significantly by segment. Globally, MNCs and their affiliates contributed 36 per cent of output in 2016, including about two-thirds of exports and more than half of imports. However, their share of medical goods and services varies hugely.

In chemicals and pharmaceuticals, MNCs accounted for 87 per cent of global value-added and 83 per cent of exports in 2016 (figure 1.6). MNCs account for such a large share in global value-added because of highly localized regulations, prompting them to set up affiliates to produce for the domestic market. MNCs play a similarly outsize role in medical devices; the 10 biggest medical device MNCs accounted for approximately 40 per cent of global sales in 2018.

In contrast, MNCs represented just 4 per cent of global value added in health and social services—among the lowest MNC contribution in all industries. Heavy regulations on entry and the dominance of the public sector explain the limited role of MNCs in medical services.

Excerpted from TRADE THERAPY – Deepening Cooperation to Strengthen Pandemic Defenses, published by The World Bank and the World Trade Organization on June 3, 2022

– to continue

– global bihari bureau