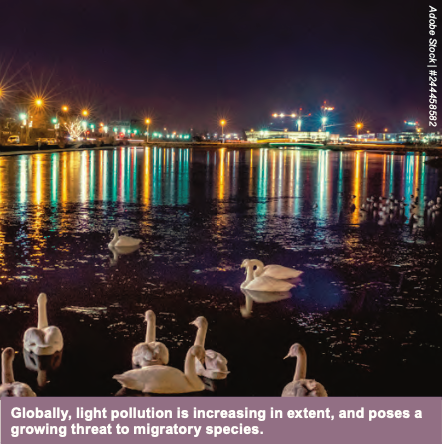

With approximately 23% of the global land area now impacted by direct emissions from artificial light sources, there is mounting evidence to suggest that artificial night-time lighting can disrupt the migratory behaviour of a wide range of species, by acting as an attractant or a repellent.

Light pollution is a contributing factor to the deaths of millions of birds annually. Many long-distance migrants are most exposed to the threat of light pollution during their migration phase, as they cross urban areas while travelling between breeding and non-breeding locations. Long-term monitoring of fatal collisions at one large building in North America, where over 40,000 dead birds have been recovered since 1978, has shown that mortality increases when the area of lighted windows is larger, indicating that with increased light comes increased deaths.

Light pollution also affects migratory mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates, though these have been less well studied. In coastal areas, artificial night-time lighting near turtle nesting sites significantly lowers the survival of turtle hatchlings, which depend on visual brightness cues for ‘sea-finding’ behaviours.

A growing area of the Earth’s surface is affected by artificial night-time lighting and the distant sky glow of a brightly lit city can disorient migrating animals. On a more local scale, excessive artificial light can also increase the likelihood of fatal collisions with buildings, wires and other structures.

Plastic, light, chemical, and noise pollution are killing migratory species! Pollution is a key driver of recent biodiversity loss worldwide. It can cause mortality directly, through toxic effects on individuals, or indirectly, by reducing food availability and degrading habitat quality. It can also adversely affect reproductive and physiological performance and natural behaviours, including migratory behaviour. Given their reliance on multiple spatially separated habitats, migratory species may be more likely to encounter a diverse range of pollutants.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, pollution is a threat to 276 Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS)-listed species (43% of those with threats documented).

Anthropogenic noise from shipping and sonar stresses and disorients migratory species

Anthropogenic noise is a major stressor that impacts many taxonomic groups, including migratory mammals, birds and fish9. Marine environments in particular are increasingly being affected by noise pollution, which is predominantly caused by activities such as commercial shipping, military sonar, seismic exploration, offshore drilling and offshore wind farms. Global noise emissions from commercial shipping, for example, are predicted to double every 11.5 years, if current rates of increase continue.

As aquatic mammals depend upon underwater sound to navigate, communicate, find prey and avoid predators, many of these species are significantly impacted by anthropogenic noise. Sustained exposure to noise can force migrating animals to alter their behaviour, can cause injury, or if loud enough, can even kill.

Underwater noise pollution from shipping vessels disrupts foraging behaviour in many cetaceans, including Harbour Porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) and Killer Whales (Orcinus orca), which spend less time feeding when noisy vessels are present. Beaked whales (Ziphiidae) are also extremely sensitive to high-intensity sounds, such as military sonar, which may play a role in fatal stranding events.

Beyond the marine environment, the likely impacts of anthropogenic noise on terrestrial migrating species that use echolocation, such as bats, are becoming clearer. For example, noise pollution can distract foraging bats, resulting in them hunting less efficiently.

Plastic pollution is widespread in many habitats and accumulates in the marine environment

Plastic pollution is increasingly ubiquitous throughout the world, from human-populated areas to remote polar habitats and the deep sea. Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, humans have produced 6.3 billion metric tonnes of plastic waste. The majority has ultimately accumulated in landfills or the natural environment. Plastic waste is typically carried by wind and rivers to the sea. Since most plastics are highly resistant to degradation, the world’s oceans therefore function as a major ‘sink’ for plastic debris.

The range of migratory species that are impacted by plastic pollution was highlighted in a recent CMS report; plastic pollution is not only pervasive in the marine environment but also affects terrestrial and freshwater species such as the Indian Elephant (Elephas maximus indicus) and the Irrawaddy Dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris). Plastic affects wildlife primarily through entanglement (whereby animals become ensnared in items like bags or nets) or through the ingestion of small plastic materials.

A major cause of entanglement in the marine environment is abandoned, lost and discarded fishing gear, which leads to ‘ghost fishing’ where equipment snags animals that are then never harvested. Although there is uncertainty surrounding the quantity of fishing gear that is lost annually, geographic hotspots where entanglement rates are likely to be high have been broadly identified in ocean gyres, along coastlines, and semi-enclosed seas, such as the eastern Mediterranean basin.

Ingestion of plastic debris can potentially impair an animal’s movement and feeding, cause intestinal blockages, or affect reproduction through the absorption of microplastics. While the effects of plastic ingestion can be difficult to assess, the inadvertent consumption of plastic debris has been shown to represent an additional source of mortality in albatrosses.

Chemical pollution and heavy metals can have an enduring impact on migratory populations

Chemical pollution, the contamination of the environment with chemicals that are not found there naturally, encompasses a vast range of potential pollutants. These include heavy metals, such as lead and mercury, oil, agricultural pesticides, industrial chemicals and organic pollutants.

Poisoning from spent lead ammunition is having a significant impact on a wide range of birds, including many migratory raptors and waterbirds that inadvertently consume lead when feeding. Approximately one million waterbirds alone are estimated to die from acute lead poisoning annually across Europe. Although it is now illegal to use lead gunshots in and around wetlands in all 27 EU countries, elsewhere, the use of lead ammunition remains a significant issue.

Marine migratory species, including cetaceans, marine turtles and seabirds, are susceptible to the harmful effects of oil spills. In 2010, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico is estimated to have caused the deaths of tens of thousands of adult and juvenile marine turtles and hundreds of thousands of birds (primarily seabirds). The mortality resulting from an oil spill can have an enduring impact on wildlife populations, particularly for long-lived species such as cetaceans. Aquatic mammals are prone to the inhalation, ingestion and dermal absorption of oil, which can compromise reproduction and survival in the long term.

Also read:

- Migratory species succumbing to anthropogenic pressure

- Migratory species: Why are they important?

- Landmark UN report reveals ‘shocking’ state of migratory species

Agricultural and industrial activity can release significant levels of toxic chemicals, such as persistent organic pollutants (POPs), into the environment. Used in pesticides and industrial chemicals, these pollutants are commonly referred to as ‘forever chemicals’ as they are resistant to environmental degradation. Despite increased regulation of POPs, they continue to be detected in migratory species such as the Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) in the Great Lakes, United States of America.

Additionally, nutrient run-off from a wide range of sources continues to pose a serious threat to wetland birds. Eutrophication, the excessive growth of algae and other aquatic plants due to an increased concentration of nutrients, leads to deoxygenation of water systems; the resulting reduction in habitat quality has cascading impacts on food webs. For example, populations of five generalist duck species associated with eutrophic water ecosystems in Finland were estimated to have halved on average since the 1990s, likely due to over-38 eutrophication and the resulting loss of feeding opportunities.

Finally, the widespread application of pesticides in intensive agriculture has been recognized as a key factor in the reported declines in the populations of many insect species. These losses can result in food shortages for a wide range of species, including the many insectivorous migratory birds.

Excerpts from State of the World’s Migratory Species prepared for the Secretariat of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (UNEP-WCMC, 2024. State of the World’s Migratory Species. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

– global bihari bureau