A Baka tribal. Photo credit: Alejpalacio

Food habits of Indigenous People -1

Hunting, Gathering and Food Sharing in Africa’s Rainforests

Forest food system of Baka people in South-eastern Cameroon

The Baka are one out of a dozen groups of Congo Basin hunter-gatherers. Around 20 ethnic groups are found in the East region of Cameroon, among which the majority speak Bantu languages. The Baka, who speak an Ubanguian language, are found throughout the southern part within a mosaic of 17 languages, which predominantly belong to the Niger-Congo phylum of Bantu languages.

The food system of the Baka, often referred to as “Pygmies” who live in the tropical rainforest of South-eastern Cameroon, is entirely dependent on the forest. An estimated 81 percent of their food is obtained through hunting, gathering and fishing activities, practised during incursions and movements in the forest, combined with shifting cultivation. Exchanges with other communities and the market provide about 19 percent of their diet.

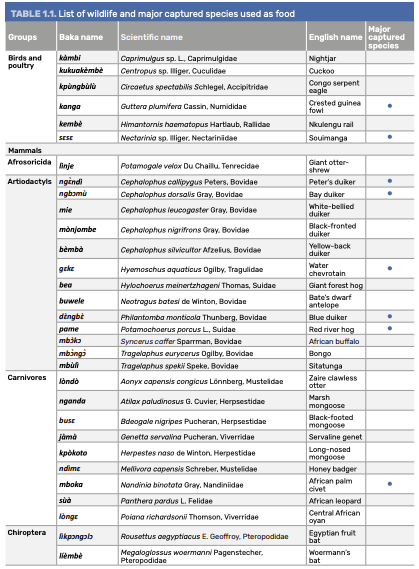

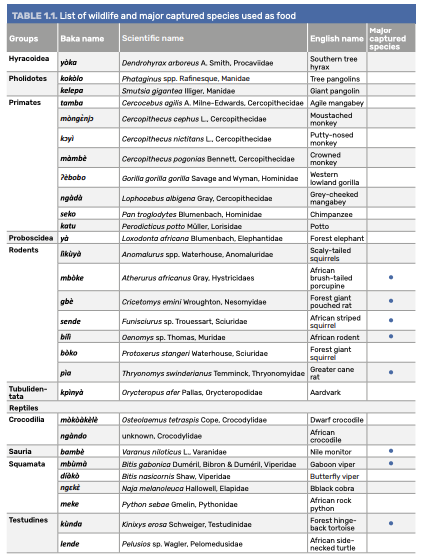

In total, the Baka use around 179 species for food. Outstandingly, the Baka are renowned for their knowledge of about 500 species of wild or ruderal plants used for medicinal, material, and spiritual purposes. Over time, the Baka had managed to maintain a resilient and self-sufficient livelihood based on forest resources, including wild edible plants, animals, Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs), fish and swiddens. The outputs of forest sourcing, namely hunting, gathering, fishing and agriculture, rely on approximately 60 animal species, more than 83 wild edible species, at least 6 common species of fish and freshwater animals, and 32 crop species that compose 12 categories of food items

The livelihood of the Baka primarily consists of an alternation between seasonal excursions into the forest and sedentary activities carried out in permanent villages along the road. They have depended entirely on forest resources for their life and culture through hunting, gathering and fishing.

Over recent decades, the Baka’s livelihoods have been influenced by changes in the macro environment, including a settlement policy and a zoning policy that has affected their extensive moves from forest to forest, as well as timber exploitation, the market economy, increased bushmeat trade and animal decline. Ultimately, such conditions are affecting food sharing amongst the Baka and the relationship between the Baka and their neighbours.

In places such as Gribe village in eastern Cameroon, the Baka are engaged in a transitional post-forager lifestyle affected by an increasingly constrained access to the forest. Aside from the existing administrative boundaries, Gribe together with 20 neighbouring villages constitutes the Konabembe canton that was formed before or during the German colonial period. The village is immediately surrounded by a mix of evergreen and semi-deciduous forest with a canopy stratum culminating 40 m to 50 m above ground. The topography is characterized by scattered gently rolling hills isolated from each other by a dense hydrographic network.

Long-distance stays in the forest in search for food items (bushmeat, freshwater resources, insects, wild tubers, honey, leaves, fruits, nuts and all sorts of spices) and non-food products (medicinal plants, various materials for building and carving) are becoming increasingly challenging and diminishing, whilst sedentary activities in the village are increasing. Shifting cultivation to produce starches and Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs), home gardening, and agroforest plantations to produce cash crops (cocoa, coffee), as well as off-farm activities (labouring in exchange for crops, and salaried jobs in logging and safari companies) are all important activities.

The relationships between the Baka and their farming neighbours are based on complementarity. Through the adoption of a lifestyle that mimics that of their neighbours and under constant incentives by governmental agencies to abandon their age-old forager way of life, the Baka are now exposed to an acute risk of losing their expertise of the forest and their rich animist culture based on a connivance with the supra-natural forces who are the masters of forest resources.

At the same time, Baka interest in NTFPs for the market is developing a new relationship with neighbours that goes beyond the traditional exchanges and barter. Despite this, the Baka are increasingly ostracized since they rarely have a voice in negotiations with the various stakeholders (authorities, private companies, protected areas managers) who meet and discuss, which in the end results in progressively reducing the Baka’s access to their ancestral forests.

The livelihood means currently practised by the Baka in Gribe are hunting, gathering, fishing, shifting agriculture, material and labour exchanges with the Bantu speaking groups, and extractivism through the harvesting for sale of NonTimber Forest Products (NTFPs). All Baka in Gribe are involved in hunting. Hunting activities are roughly categorised into three types: maka, mumbato and sendo. The term maka refers to large-scale expeditions to track big animals such as red river hog and elephant. These expeditions are carried out in groups of about 5 to 10 men who journey around the forest for more than a week. The mumbato type of hunting involves a group of two to three men for about one week. Oftentimes, these groups are based in forest camps from where they go to trap animals and collect NTFPs. The sendo type is day hunting, which is a shorter outing from a semi-residential settlement or a forest camp. In addition, the Baka use a special trap called mɛ̀ ndàmbà to capture mice and rats and slingshots to shoot small birds around the farming camp. About half of the captured animals are traded and the other half are used for self-consumption.

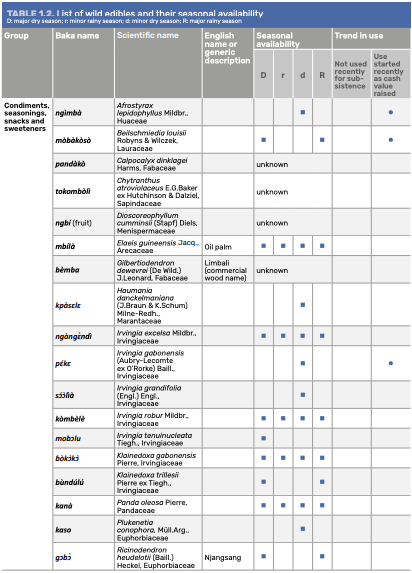

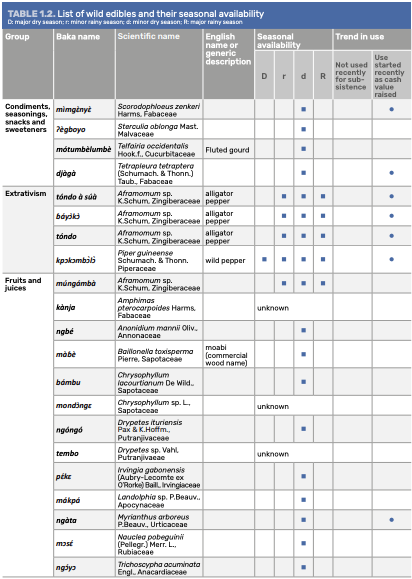

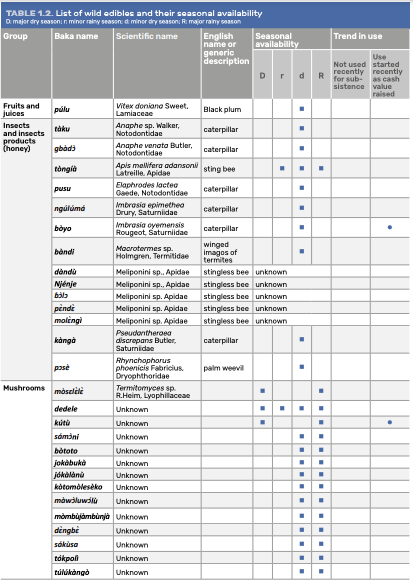

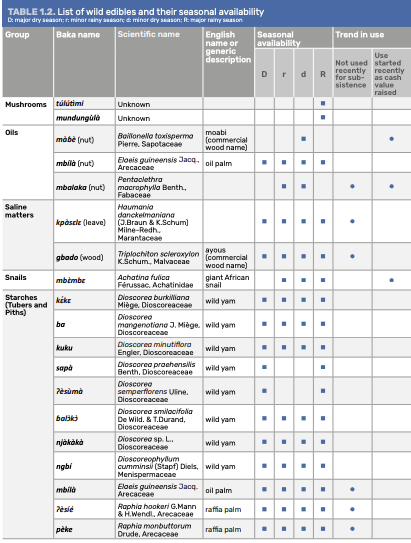

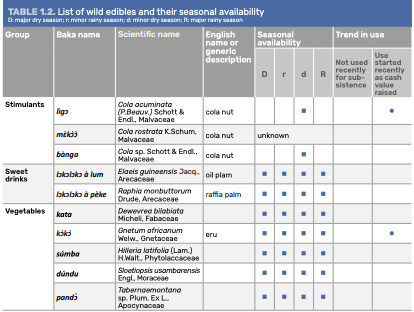

However, amongst the Baka, agriculture has increased over recent decades. A variety of plants, mushrooms and other wild edibles are collected by the Baka for subsistence and household economy. Table 1.2 shows the major wild edibles collected by food group, with specification of their scientific and Baka names. Eight species of wild yams (Dioscorea spp.) are notably important for subsistence. Out of the eight, two species of yam renew their tubers annually and are spread in large patches within the forest area. During the major dry season, the Baka undertake long-term harvesting expeditions for these two species to ensure their food security. By contrast, all the other yams species have perennial tubers and are more randomly distributed throughout the forest.

About 30 species of wild fruits are collected and consumed as oil, oily condiments, seasonings and snacks. Amongst them, kernels of kanà (Panda oleosa), seeds of màɓè (Baillonella toxisperma), and kernels of several species of Irvingiaceae trees are most frequently used. In addition, kernels of pɛ́ kɛ (Irvingia gabonensis) are of particular importance for local diets and cash income. This species is available only in the minor dry season, at which time most Baka move to the forest and camp for two to three months to collect the kernels together with other forest resources. This seasonal camp is accordingly called bàlà pɛ́ kɛ (Irvingia camp).

Other major wild edibles collected primarily for income are fruits of Aframomum spp., ngìmbà (Afrostyrax lepidophyllus), and gɔbɔ (Ricinodendron heudelotii, njangsang), which are commonly sold as seasonings.

As vegetables, the leaves of five species are collected, amongst which kɔ̀ kɔ (Gnetum africanum) is the most frequently consumed and easy to gather. Mushrooms are highly valued and the Baka have a wealth of knowledge regarding their diversity, edibility and ecologies. They eat around 20 species with different seasons of occurrence. The largest forest mushrooms are the Termitomyces species that grow on mounds of Macrotermes termites. Monospecific forest patches of bèmba (Gilbertiodendron dewevrei) are known for their incredible diversity of symbiotic mushrooms.

Invertebrates are also important components in Baka diets. The most popular are caterpillars, which are highly seasonal. Each species receives the name of the host tree on which they feed exclusively. Sùsu (winged termite imagos), which emerge from the ground, mounds or aerial nests around the end of the minor dry season, are highly favoured.

As emergence time approaches, children and adults observe termite mounds and nests almost every day. Imagos of mbìle species emerging from the ground are captured and immediately eaten by children. For bàndi termites, adult men will dig out soldiers from the mounds and cook them as a soup ingredient. Weevil larvae are extracted from the trunk of Raffia palms (Raphia spp.) that they parasitize in swampy forests. Large Achatina snails are coveted by children and women and are easy to catch.

Sting bees (Apidae) and stingless bees (a dozen species of Melliponinae) produce a diversity of honey made from different flowers throughout the year. Honey gathering is one of the most culturally important activities amongst the Baka and embeds a set of knowledge, expertise and physical skill: bee nests are often found in hollow tall trees, sometimes very high above the ground. Finding bees from the ground requires the ability to perceive the slight appearance, sound and particular atmosphere of bees. Lìɓɛnjì (insect detritus) discharged by the bee workers and accumulated at the base of the tree are indirect clues for localizing a nest. Apis nests require the gatherer to climb the tree, while cutting it down is necessary to access stingless bee nests.

Fishing

Amongst a vast range of fishing methods reported from the East region, the Baka most frequently practise ngúma (dam fishing), hand-gathering, njɛ́ ɛ̀ njɛ̀ (angling) and mátìndì (trapping).

Crops

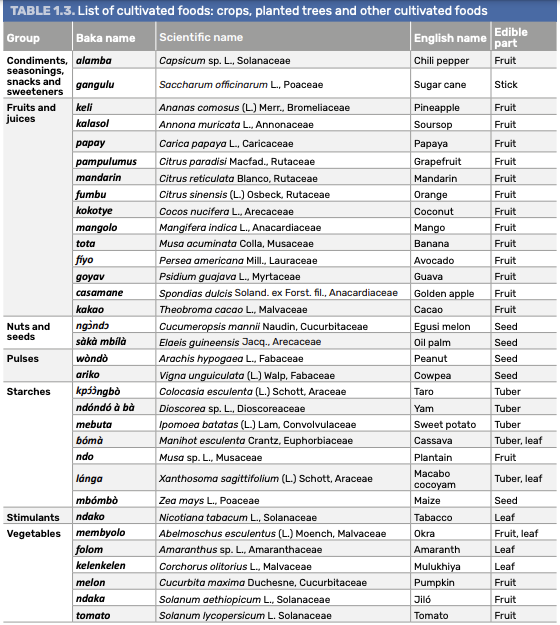

Main food crops are plantain, banana, cassava, cocoyam, sweet potato, maize, yam, taro, okra and chili pepper. Peanuts and cowpeas are grown more occasionally, when seeds are available. Cocoa, the sole cash crop, is sometimes produced in small plantations, accounting for only about 5 percent of the total cultivated area.

A limited amount of plantain is occasionally sold on request. Apart from the fields, plantain, banana, cocoyam and papaya are also planted around the farming camp. Thirty-three crops were recorded in total (Table 1.3). Of these, plantain, banana, cassava, cocoyam and okra are cultivated by almost all the households. Peanut is very popular as an oily condiment yet few households can procure seeds. Only a few fruit trees are planted around the settlement, whilst others, such as papaya, occur spontaneously. Crops with multiple varieties are plantain (28), banana (5), cassava (18), cocoyam (3), peanut (4) and maize (2). With 28 and 18 varieties, respectively, plantain and cassava count notably more varieties than other crops. Five varieties of plantain and three of cassava predominate. All of these varieties are recognized as local and ancient.

Food taboos are a good illustration of existing socio-cultural regulations in the Baka community. Many foods should not be eaten, depending on individual, gender, social status and clan affiliation. For instance, whilst processing extraction of oil from màɓè seeds, women avoid eating any bushmeat. When conducting dam fishing, women will not eat red river hog, monkey or honey, as a means to prevent misfortune in catching large fish. When the forest spirit called kòse gets angry, men will interrupt hunting and share with the spirit tubers of ba (Dioscorea mangenotiana, wild yam), along with honey and cooked cassava flour, to calm it down. Having dozens of food prohibitions of this type is not meant primarily to sustain conservation goals. Rather, what is at stake is to gather food resources successfully and to ensure a healthy livelihood. This requires maintaining a balanced relationship with the supra-natural forces, which are the custodians of natural resources. Moderation dictates the humble attitude of the Baka vis-à-vis forest resources. Food proscriptions participate in this moderation and, incidentally, contribute to mitigating excessive exploitation of resources.

(Source of the article: Indigenous Peoples’ food systems: Insights on sustainability and resilience from the front line of climate change (Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations)

– global bihari bureau