Scientists install a Cosmic Ray Neutron Sensor to monitor snow accumulation and melting. This data helps track the glacier’s retreat and its impact on local water resources. ©Gerd Dercon

At an elevation of 5,100 meters above sea level, the atmosphere surrounding Huayna Potosí glacier in Bolivia is thin and fragile due to the altitude. The wind glides over the ice in sweeping, purposeful motions, sculpting a terrain that exists in a delicate balance between resilience and decay. While the temperature is chilly, it doesn’t always dip to freezing along the mountainside.

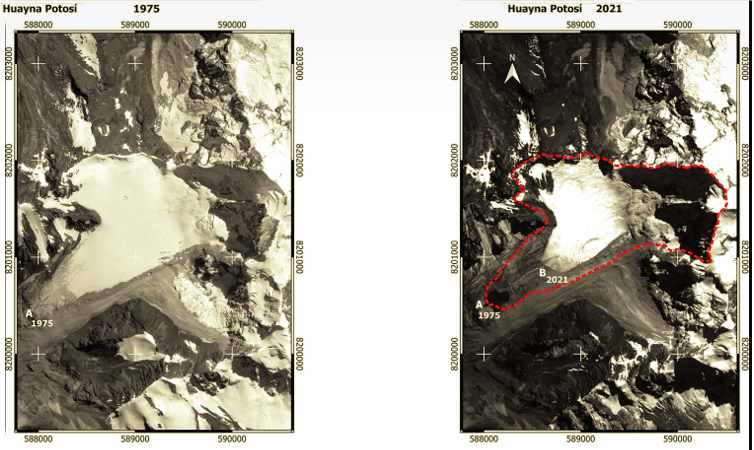

Where once a thick expanse of blue ice dominated the valley, now bare rock protrudes like exposed bone. Each year, the Western Huayna Potosí Glacier shrinks and retreats by about 24 meters, leaving behind a trail of scattered stones and a meltwater lake that was nonexistent in 1975, signifying the glacier’s former extent.

A group of scientists from the Andes and the Himalayas, hailing from Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, China, Ecuador, and Nepal, rise before dawn to commence their climb, fully aware that they must descend before nightfall when the likelihood of accidents escalates. The high altitude complicates breathing, compelling them to advance slowly and with intention. They navigate in a single line, taking care to steer clear of concealed crevasses that could engulf a person. At the glacier’s heart, they set up a device composed of panels and wires, designed to patiently interpret the mountains’ silence.

Their efforts are technically backed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) through the Joint FAO/IAEA Centre of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture, with logistical and financial support from the IAEA’s technical cooperation program.

Among the two sensors meticulously placed by the team on the glacier is a cosmic ray neutron sensor, which efficiently and continuously gauges the amount of water accumulating on the glacier in the form of snow. This snow is vital for the glacier’s survival, and each measurement serves as a fleeting glimpse into the glacier’s dwindling existence.

The retreating ice signifies more than just the loss of beautiful landscapes; it represents significant disruption for those who depend on its water resources. Scientists are gathering crucial data from these high-altitude glaciers, which aids researchers in forecasting the far-reaching impacts of ice melt on both ecosystems and local communities, ultimately seeking strategies for adaptation.

Even after the scientists leave, their equipment will continue to operate, sending signals via satellite that transcend the mountain ranges—a digital archive that retains information about what the ice can no longer preserve.

“Current glacial retreat now functions as a thermometer of accelerating climate shifts, with its rapid pace signalling the urgency of rising global temperatures,” says Gerd Dercon, Head of the Soil and Water Management and Crop Nutrition Laboratory of the Joint FAO/IAEA Centre. “As the ice melts and refreezes, it reveals not only the changes in climate but also the fragile dependencies human civilization has on these frozen reservoirs.”

In the valleys below, countless individuals rely on the glacier’s water. Llamas and alpacas thrive in the lush grasslands, nourished by the seasonal meltwater that has sustained this high-altitude ecosystem for generations. Farmers depend on this water for irrigation to cultivate their crops and nourish their livestock, while one million residents of El Alto, a city near Bolivia’s capital, La Paz, rely on it for their drinking water supply.

For countless generations, the ice fields have acted as a silent agreement between the mountains and the communities that thrive in their shadow, providing water at a rate that nurtured life. However, this agreement is now unravelling.

The causes are evident. Global temperatures are on the rise, leading to the melting of glaciers worldwide, and in Bolivia, this crisis is intensifying. Strong winds carry sediments from areas devoid of ice, depositing them onto the glacier’s surface, which darkens it and enhances heat absorption.

By studying the sediments released from regions now exposed due to glacial retreat and accumulating in lakes and reservoirs, researchers are not only monitoring how the ice’s decline affects sediment distribution but are also revealing wider environmental changes. These climate-induced shifts could have significant implications for soil fertility, water quality, and the chemistry of water sources.

Weather patterns such as El Niño exacerbate the warming, resulting in unpredictable precipitation and accelerated melting. Experts warn that if these trends persist, the glacier on Western Huayna Potosí—once considered a reliable source of drinking water by locals—could completely disappear within two decades.

“Stopping the retreat of the glacier will not be possible,” says Dercon. “But we have to capture the water in several ways.”

In Bolivia, communities are responding by constructing additional reservoirs, refurbishing older ones, and raising dam walls. The land must also be managed differently, designed to retain water rather than allow it to run off, with soil cultivated to absorb moisture. Key to this effort is reforesting native trees and curbing overgrazing by llamas and livestock, which are essential for fostering healthy soils and promoting land regeneration.

Raising awareness among decision-makers and mobilizing resources to address impending changes is a crucial initial step and a significant outcome of the expeditions. This effort has led to the creation of an international monitoring network spanning the Andes and the Himalayas. This network has shed light on how climate change is affecting the cryosphere—regions covered by ice—and the consequences of glacier retreat for those living downstream.

It is clear that these glaciers, once considered permanent fixtures, are disappearing more rapidly than anticipated. The time to protect what remains is now. In the Bolivian highlands, government agencies and farmers are working together to capture the water released from melting glaciers through reservoirs and dams, enhancing their capacity to store water. Additionally, new agreements are being established regarding water usage to prevent future conflicts. By collaborating with governments and farmers to develop solutions based on glacier data, scientists trained by the FAO and IAEA through their Joint Centre and technical cooperation programs are raising awareness and seeking solutions for a future that may exist without glaciers.

Source: The FAO News And Media Office, Rome

– global bihari bureau