Rome: The world prepares to celebrate the first-ever International Day of Potato on May 30 with the theme of “Harvesting Diversity, Feeding Hope”.

As the third most consumed food crop globally, after rice and wheat, potatoes are a staple in the diets of billions, forming an element in the diet of some two-thirds of the global population. Despite a 17 per cent decrease in the global potato area from 2000 to 2020, total production increased by 11.25 per cent thanks to improved varieties and agronomic practices. A total of 159 countries in the world have potato crops on a total of 17.8 million hectares. 374 million tons of potatoes are produced in the world annually.

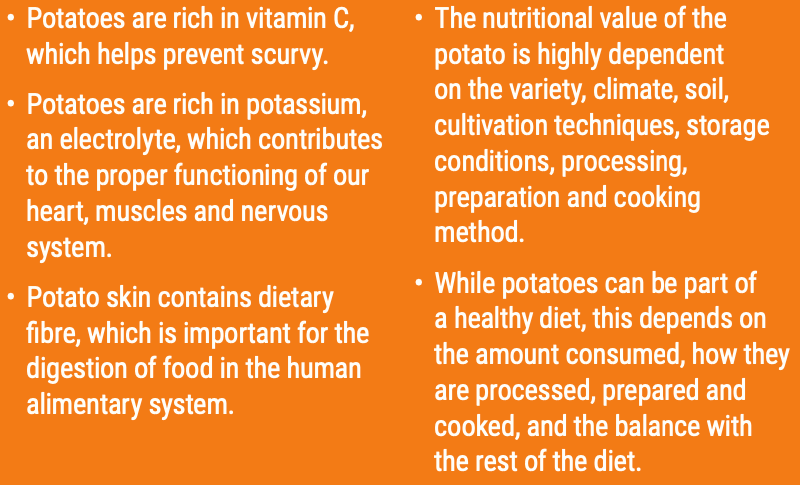

Potatoes contain antioxidants, which are natural compounds that help protect the body against damage. These antioxidants can contribute to maintaining healthy cholesterol levels, with the potential to support heart health.

Potatoes are also used to produce bio-based products like biodegradable plastics. Potato starch is being creatively used as a sustainable alternative to traditional plastics. These materials based on potato proteins and starch can be used for various packaging, like food containers and medicine capsules. Plus, they’re gluten-free and environmentally friendly, making them a smart choice for the food industry.

Thus, the crop that feeds billions is important in combating hunger and poverty and addressing environmental threats to agrifood systems.

Potatoes contribute to food security and create livelihood opportunities

Potatoes are not just a staple in the diets of many people but also provide opportunities for employment and sustainable economic growth along their value chains. With around 5,000 varieties, the diversity of potatoes plays a vital role in global food security and nutrition and in helping them adapt to different environments and tackling climate change. Small-scale family farmers, a significant proportion of whom are women, play important roles in safeguarding the crop’s diversity.

A reason why maintaining the diversity of potatoes is crucial is that over-reliance on a few varieties increases vulnerability to pests and diseases and the impacts of climate change.

Remarkably, there are about 180 wild relatives of the cultivated potato, with a wide range of desirable heritable traits, including adaptability to different environments and production systems; resistance to pests and diseases; and high densities of nutrients. The variations in size, colour and shape of the tubers are also astounding. Conserving the wild varieties, even though they may not be palatable to humans, is also critical because their heritable traits can be used to increase the resilience and nutritional qualities of cultivated varieties through plant breeding. These wild relatives, though many may be unsuitable for human consumption, are therefore a veritable pool of ‘raw materials’ for breeding progressively superior varieties of potato that are adapted to changing environmental conditions; resistant to new biotypes of pests and diseases; and meet market demands and consumer preferences.

Originating in the Andes Mountains, the potato was known as the “flower of ancient Inca civilization”, for whom it was a staple crop. “It was like bread in France, or rice in southern China,” says Charles C. Mann, the author of 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. A 12,000-hectare potato park in the Peruvian Andes is one of the few conservation initiatives in which Indigenous Peoples are managing their potato genetic resources and thereby protecting traditional knowledge.

Potato was introduced to Europe in the 16th century, from where it subsequently spread to the rest of the world. In just five centuries, potatoes have become a key food crop for farmers and consumers across the globe.

In Europe, the potato reduced reliance on cereal crops as a staple and contributed to the process of urbanization by increasing the food supply. In the Qing Dynasty in China, potato was credited with saving lives by helping to curb starvation. During times of conflict, with World War II as a notable example, potatoes played a crucial role in assuring food security thanks to their ability to produce relatively high yields and be consumed with minimal processing.

However, every coin has two sides – an apt expression to reflect the history of potato. Ireland’s Great Famine of the 1840s is a stark example of how a lack of diversity in the genetic base and cropping systems can lead to disastrous outcomes. The potato late blight, caused by Phytophthora infestans, decimated potato crops uniformly due to a lack of genetic diversity, resulting in poor yields leading to widespread famine and waves of emigration.

In December 2023, the United Nations General Assembly tasked the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) with facilitating the annual observance of the International Day of Potato. This International Day of Potato aligns with the FAO Strategic Framework 2022-31, which supports the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development through the transformation to more efficient, inclusive, resilient and sustainable agrifood systems for better production, better nutrition, a better environment and a better life, leaving no one behind.

Today, some estimates suggest that the consumption of fresh potatoes is on the decline, while consumption of highly processed foods, including those made from potatoes, is on the rise in most countries around the world – a trend that unfortunately is contributing to several forms of malnutrition.

“When the general public hear of potatoes what comes to their mind firstly might be french fries or potato chips which are not necessarily the healthiest way of consuming potatoes,” says FAO agronomist Makiko Taguchi. The International Day will also serve to showcase different healthier ways of preparing and consuming potatoes, “which links to varietal diversity because certain varieties are more nutritious,” she adds.

FAO stated its work on the potato encompasses support for farmers and Indigenous Peoples to build capacity in managing common diseases such as Late Blight, fostering innovative solutions to grow potatoes with minimal resources and promoting cooperation with diverse actors along the crop’s value chain.

– global bihari bureau