China should allow independent investigators full and unhindered access to Xinjiang, Tibet, and across the PRC, says the USA

Geneva/Washington/Beijing: On August 31, 2022 – the last day in the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) released a report indicting China for human rights violation minority Ughyrs in the Xinjiang province of the country.

“The extent of arbitrary and discriminatory detention of members of Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim groups, pursuant to law and policy, in context of restrictions and deprivation more generally of fundamental rights enjoyed individually and collectively, may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity,” the report states.

The scathing verdict by the OHCHR was immediately lapped up by the United States of America, and its Secretary of State Antony J Blinken said the report “deepens and reaffirms our grave concern regarding the ongoing genocide and crimes against humanity that PRC government authorities are perpetrating against Uyghurs, who are predominantly Muslim, and members of other ethnic and religious minority groups in Xinjiang”. He added that the USA will continue to work closely with its partners, civil society, and the international community to seek justice and accountability for the many victims. “We will continue to hold the PRC [People’s Republic of China] to account and call on the PRC to release those unjustly detained, account for those disappeared, and allow independent investigators full and unhindered access to Xinjiang, Tibet, and across the PRC,” he said.

While the OHCHR offered to support China in addressing the issues and recommendations articulated in the assessment, China dismissed the OHCHR report as “completely illegal, null and void”. It accused the “so-called assessment” to be orchestrated and produced by the US and some Western forces. “It is a patchwork of disinformation that serves as a political tool for the US and some Western forces to strategically use Xinjiang to contain China. The OHCHR’s so-called assessment is predicated on the political scheme of some anti-China forces outside China. This seriously violates the mandate of the OHCHR and the principles of universality, objectivity, non-selectivity and non-politicization,” Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin claimed in Beijing.

Earlier, on August 31, 2022, too, on the last day of Bachelet in office, China had “firmly” opposed the release of the “so-called assessment” on Xinjiang by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and hoped that the High Commissioner “will make the right decision”.

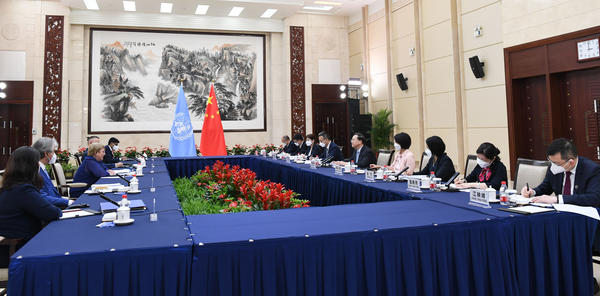

Bachelet visited China from May 23 to 28, 2022, where Chinese President Xi Jinping told her that in terms of human rights protection, no one can claim perfection and there is always room for improvement. The Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi assured her of China safeguarding the ethnic minorities’ rights was an important part of its work. She visited Xinjiang where she had field trips in Kashgar where she visited Kashgar prison and the Kashgar Experimental School, a former Vocational Education and Training Centre (VETC), among other places, and Urumqi. She had conversations with people from various communities, including ethnic minorities, academics, and representatives of different social sectors. The Chinese government also made a presentation before her on “the measures taken and achievements made in the region on counter-terrorism and deradicalization, social and economic development, ethnicity and religion, and labour rights protection”. She was the first UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to visit China in 17 years. She later told media persons in Geneva on May 28, 2022, that in advance of her visit, her Office and she met virtually with a number of civil society organisations that are working on issues relating to Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong and other parts of China. She, though, had claimed then that her visit was not an investigation – “official visits by a High Commissioner are by their nature high-profile and simply not conducive to the kind of detailed, methodical, discreet work of an investigative nature”. She had claimed that the visit was an opportunity to hold direct discussions – with China’s most senior leaders – on human rights, to listen to each other, raise concerns, explore and pave the way for more regular, meaningful interactions in the future, with a view to supporting China in fulfilling its obligations under international human rights law.

In its 45-page report on China, the OHCHR, however, claimed that serious human rights violations are committed in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China (XUAR) in the context of the Government’s application of counter-terrorism and counter-“extremism” strategies.

The OHCHR in a statement claimed that its assessment is based on a “rigorous review of documentary material currently available to the Office, with its credibility assessed in accordance with standard human rights methodology”.

The report noted that the Chinese “anti-terrorism law system” is based on vague and broad concepts that grant significant discretion to diverse officials as to their interpretation and application.

“Methods set out under the framework to identify and assess problematic conduct are simplistic and prone to subjectivity and do not appear to be based on empirically obtained evidence that establishes the links between the indicators of conduct relied on and terrorism or violent extremism. Furthermore, the legal consequences attached to such conduct are unpredictable and insufficiently regulated. Authorities are granted broad investigative, preventive and coercive powers with limited safeguards and independent judicial oversight,” the OHCHR stated.

The report claimed that the descriptions of detentions in the “Vocational Education and Training Centres”(VETCs) in the period between 2017 and 2019 gathered by OHCHR were marked by patterns of torture or other forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, other violations of the right of persons deprived of their liberty to be treated humanely and with dignity, as well as violations of the right to health.

Refuting the Chinese Government’s claims that the VETC facilities have been closed since 2019, the OHCHR report claimed that even if the VETC system has since been reduced in scope or wound up, as the Government has claimed, the laws and policies that underpin it remain in place.

“There appears to be a parallel trend of an increased number and length of imprisonments occurring through criminal justice processes, suggesting that the focus of deprivation of liberty has shifted towards imprisonment, on purported grounds of counter-terrorism and counter-“extremism,” it stated.

It reminded the Chinese Government that it is the latter’s primary duty to ensure that all laws and policies are brought into compliance with international human rights law and to promptly investigate any allegations of human rights violations, ensure accountability for perpetrators and provide redress to victims.

“Individuals who are arbitrarily deprived of their liberty should be immediately released. As the conditions remain in place for serious violations to continue and recur, these must also be addressed promptly and effectively. The human rights situation in XUAR also requires urgent attention by the Government, the United Nations, intergovernmental bodies and human rights systems, as well as the international community more broadly,” the report stated. It added that the enforcement of the Government’s counterterrorism and “extremism” policies are accompanied by allegations of extensive forms of intensive surveillance and control.

The OHCHR report claimed that China has a consistent pattern of invasive electronic surveillance that can be, and is, directed at the Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim populations, whereby certain behaviours, such as downloading Islamic religious materials or communicating with people abroad, can be automatically monitored and flagged to law enforcement as possible signs of “extremism” requiring police follow-up, including potential referral to a VETC facility or other detention facilities.

The report noted that several researchers, predominantly based on a detailed analysis of publicly available satellite imagery, consider that a large number of mosques have been destroyed in XUAR over the last years. It stated that analysis of satellite imagery in the public domain indicates that many religious sites appear to have been removed or changed in their characteristic identifying features, such as the removal of minarets.

Persons interviewed by OHCHR also recounted that, at least since 2014, there were closures of schools providing instruction in Uyghur and/or Kazakh language, and that teachers were being progressively removed from their bilingual duties.

The implementation of these strategies, and associated policies in XUAR has led to interlocking patterns of severe and undue restrictions on a wide range of human rights. These patterns of restrictions are characterized by a discriminatory component, as the underlying acts often directly or indirectly affect Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim communities.

The implementation of the purported counter-terrorism and “extremism” policies in XUAR has had deep impacts on families. The widespread arbitrary deprivation of liberty of Uyghurs and other predominantly Muslim communities in XUAR, often shrouded in secrecy, has led to many families being separated and unaware of the whereabouts of their loved ones.

There are “credible indications” of violations of reproductive rights through the coercive enforcement of family planning policies since 2017. The lack of available Government data, including post-2019, makes it difficult to draw conclusions on the full extent of current enforcement of these policies and associated violations of reproductive rights. Several women interviewed by OHCHR raised allegations of forced birth control, in particular, forced IUD placements and possible forced sterilisations with respect to Uyghur and ethnic Kazakh women. Some women spoke of the risk of harsh punishments including “internment” or “imprisonment” for violations of the family planning policy. Official population figures indicate a sharp decline in birth rates in XUAR from 2017. Data from the 2020 Chinese Statistical Yearbook, covering 2019, shows that in the space of two years the birth rate in Xinjiang dropped approximately 48.7 per cent, from 15.88 per thousand in 2017 to 8.14 per thousand in 2019. The average for all of China is 10.48 per thousand.

With respect to the allegations of forced labour in XUAR that are not necessarily connected to VETC facilities, some publicly available information on “surplus labour” schemes suggests that various coercive methods may be used in securing “surplus labourers”.

Claims of family separations and enforced disappearances were among the first indicators of concern about the situation in XUAR, with large numbers of people alleged to be “forcibly disappeared” or “missing”. Approximately two-thirds of the 152 outstanding cases in China of the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances pertain to XUAR over the period 2017-2022.

The Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances (CPED) defines such disappearance as “the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which places such a person outside the protection of the law”. Although China is not a party to the Convention on Enforced Disappearances, it is bound by the prohibition of enforced disappearance that is encompassed by other human rights treaties to which it is a party.

The Xinjiang Victims Database, a platform used by exiled family members seeking the whereabouts of their loved ones in XUAR, currently has hundreds of entries of alleged “missing persons”

These human rights violations, as documented in this assessment, flow from a domestic “anti-terrorism law system” that is deeply problematic from the perspective of international human rights norms and standards. It contains vague, broad and open-ended concepts that leave wide discretion to officials to interpret and apply broad investigative, preventive and coercive powers, in a context of limited safeguards and scant independent oversight. This framework, which is vulnerable to discriminatory application, has in practice led to the large-scale arbitrary deprivation of liberty of members of Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim communities in XUAR in so-called VETC and other facilities, at least between 2017 and 2019.

According to the Chinese Government’s 2019 White Paper on “Vocational Education and Training in Xinjiang” and relevant legal provisions, three categories of individuals can be held in such centres. The first category includes individuals who have been convicted for terrorist or “extremist” crimes and who are, upon completion of their sentence “assessed as still posing a potential threat to society”.91 Such people are, according to the law, sent to VETC facilities by a court decision.92 The second category includes “people who were incited, coerced or induced into participating in terrorist or extremist activities, or people who participated in terrorist or extremist activities in circumstances that were not serious enough to constitute a crime”. Those people can be referred to VETC facilities upon a decision of the police. The third category consists of “people who were incited, coerced or induced into participating in terrorist or extremist activities, or people who participated in terrorist or extremist activities that posed a real danger but did not cause actual harm”.

The OHCHR report claimed there are allegations of instances of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) in VETC facilities, including rape, which also appears credible and would in themselves amount to acts of torture or other forms of ill-treatment. However, the report mentioned that the Chinese Government has denied such allegations, asserting in its 2019 White Paper on “Vocational Training and Education in Xinjiang” that the rights of “trainees” are fully respected.

“The Government’s blanket denials of all allegations, as well as its gendered and humiliating attacks on those who have come forward to share their experiences, and have added to the indignity and suffering of survivors,” the report stated, pointing out Chinese Government-affiliated media has regularly disseminated promotional videos about VETC facilities. Those interviewed in such videos either welcomed their stays or said that it had helped them from being drawn to terrorism or “extremism”. “

Those interviewed by OHCHR, in contrast, said they were explicitly told by guards to be positive about their experience in the facility when outsiders or family members would visit. One interviewee, for example, reported that ahead of a visit by a foreign delegation they were told to say that “everything was fine”, that they could return home every night, that they were studying and that the food was acceptable.106 Moreover, some interviewees reported being explicitly prohibited to disclose any information about the facility once released, with some having to sign a document to this effect. The treatment of persons held in the system of so-called VETC facilities is of equal concern. Allegations of patterns of torture or ill-treatment, including forced medical treatment and adverse conditions of detention, are credible, as are allegations of individual incidents of sexual and gender-based violence. While the available information at this stage does not allow OHCHR to draw firm conclusions regarding the exact extent of such abuses, it is clear that the highly securitised and discriminatory nature of the VETC facilities, coupled with limited access to effective remedies or oversight by the authorities, provide fertile ground for such violations to take place on a broad scale.

The Chinese authorities continue to openly criticise victims and their relatives now living abroad for speaking about their experiences in XUAR, discrediting stories that are made public.

Intimidations and threats were also reported by former detainees, some of whom were forced to sign a document ahead of their release, pledging not to speak about their experience in the VETCs. In the words of one interviewee: “We had to sign a document to remain silent about the camp. Otherwise, we would be kept for longer and there would be punishment for the whole family.”

According to the report, patterns of intimidations, threats and reprisals were consistently highlighted by interviewees. Two-thirds of the interviewees with whom OHCHR spoke asserted having been victims of some form of intimidation or reprisal, in particular threatening phone calls or messages, mostly by Chinese, but also from neighbouring States to fellow exiled Uyghurs or Kazakhs, or by family members, possibly acting at the behest of the authorities, following statements or advocacy in relation to XUAR. Some also claimed that family members in XUAR had been intimidated or suffered direct reprisals as a result of public engagement overseas, including being taken to a VETC or other facility.

The extent of arbitrary and discriminatory detention of members of Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim groups, pursuant to law and policy, in the context of restrictions and deprivation more generally of fundamental rights enjoyed individually and collectively, may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.

It may be mentioned that XUAR is China’s largest region, covering one-sixth of its total territory, with a population of 25.85 million. It is rich in resources such as coal, gas, oil, lithium, zinc and lead, as well as being a major source of agricultural production, such as of cotton. As it shares external borders with Afghanistan, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Pakistan, Russian Federation and Tajikistan, the region also provides important routes and access to Central Asian markets and beyond.

Demographically, XUAR has been one of the fastest growing regions in China and its ethnic composition has gradually shifted since 1949.17 In 1953, at the time of the first census, over 75 per cent of the total population in the region was constituted by Uyghurs, who are predominantly Sunni Muslim, with ethnic Han Chinese accounting for seven per cent. According to the latest census and the Government’s White Paper on “Xinjiang Population Dynamics and Data”, while the overall population of both Han and Uyghur ethnic groups has grown, the Uyghur population now constitutes about 45 per cent of the region’s total and Han Chinese about 42 per cent.

In July 2009, riots broke out in the regional capital Urumqi. The then United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights called for an investigation into the causes of the violence. The Government reported that “from 1990 to the end of 2016, separatist, terrorist and extremist forces launched thousands of terrorist attacks in Xinjiang, killing large numbers of innocent people and hundreds of police officers, and causing immeasurable damage to property”. In May 2014, in the wake of these developments, the Government launched what it termed a “Strike Hard” campaign” to combat terrorist threats, which it linked to religious “extremism” and separatism in XUAR.29 In a 2019 White Paper, the Government stated that “since 2014, Xinjiang has destroyed 1,588 violent and terrorist gangs, arrested 12,995 terrorists, seized 2,052 explosive devices, punished 30,645 people for 4,858 illegal religious activities, and confiscated 345,229 copies of illegal religious materials”.

It was in late 2017, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) began receiving increasing allegations by various civil society groups that members of the Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim ethnic minority communities1 were missing or had disappeared in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “XUAR” and “China”). In 2018, the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances reported a “dramatic” increase in cases from XUAR “with the introduction of “re-education” camps in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region by the Government of China”. Numerous research and investigative reports published since that time by a diverse range of non-governmental organizations, think-tanks and media outlets – as well as public accounts by victims – have alleged arbitrary detention on a broad scale in so-called “camps”, as well as claims of torture and other ill-treatment, including sexual violence, and forced labour, among others.

During its review of China’s periodic report in August 2018, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed alarm over numerous reports of the detention of large numbers of ethnic Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities, under the pretext of countering religious extremism in XUAR. The Government stated that “vocational training centres exist for people who had committed “minor offences.” In subsequent policy papers, the Government presented such centres as part of its strategies to counter terrorism and to prevent or counter “extremism” in XUAR, while at the same time contributing to development, job creation and poverty alleviation in the region.

In light of the breadth and gravity of the allegations, and the nature of the information received, OHCHR sought access to XUAR to verify claims since 2018. In parallel, and further to its global mandate under General Assembly resolution 48/141 and within existing resources, OHCHR stated it continues to monitor the situation and assess the allegations, including by reviewing and critically analysing publicly available official documentation, as well as research material, satellite imagery and other open-source information, examining their origin, credibility, weight and reliability in line with standard OHCHR methodology.

– global bihari bureau