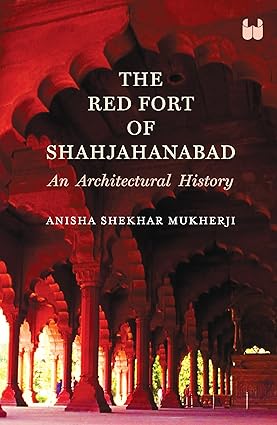

Red Fort, Delhi

Literary Speaking: Red Fort – The most magnificent palace in the East

The Red Fort of Delhi was once termed the ‘most magnificent palace in the East, perhaps in the world’, by James Ferguson, a pioneering Scottish architectural historian in the 19th century, when he came across the remains of the fort in the mid-19th century.

The Red Fort of Delhi was once termed the ‘most magnificent palace in the East, perhaps in the world’, by James Ferguson, a pioneering Scottish architectural historian in the 19th century, when he came across the remains of the fort in the mid-19th century.

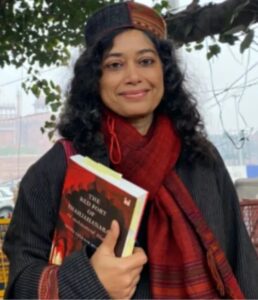

“We must remember that at that time the Red Fort was already about 200 years old and many of its most glorious structures had already been destroyed,” reminds Anisha Shekhar Mukherji, the author of The Red Fort of Shahjahanabad: An Architectural History.

The Red Fort or Lal Qila was built on the grandest scale under the patronage of Shah Jahan, the fifth emperor of the Mughal dynasty, in the 17th Century, attracting admiration from visitors from across the world. Shah Jahan got it built when he shifted his expanding empire’s capital from Agra to Delhi.

The Mughal Empire was large and the richest in the world under Shah Jahan. So, it was natural that the complex was magnificent, attracting attention because of its beautifully constructed and planned buildings, and because the entire complex functioned so well in the social, economic, and political context of that time.

“The individual buildings, in terms of their proportion, their detailing and their decoration, overawed whoever encountered them. The entire Fort functioned as a well-conceived whole to its contemporary city of Shahjahanabad, most of which spread out to the west from its main gate called the ‘Lahori Gate’. The entire complex was a sequence of formal spaces that led up almost in a crescendo to the different important buildings,” Mukherji elaborates.

“The Red Fort performed many functions – it contained the palace of the emperor and his family, the administrative sections, the military, the places of interaction with the public, courts of justice; with splendid gardens, shopping areas, karkhanas, everything,” she explains. According to her, everything was very coherently knit together spatially through a series of large forecourts that increased in size and grandeur as you approached the Fort. These forecourts were entered through a succession of gateways, which led you close to the emperor’s throne in the Diwan-i-Aam.

Mukherji is an architect with a specialization in conservation and works as an independent designer, researcher, and conservation consultant. She is also the author of significant books on India’s history, culture, and architecture, and teaches as a visiting faculty at the School of Planning and Architecture in Delhi.

“The book explains the original design and form of the Fort. The eastern face of the Fort, which is towards the Yamuna River, and which is furthest from the public gateway, is where the Emperor’s palace and those of his family were situated. Every morning, without fail, the emperor came out onto his balcony in a tower known as the Mussaman Burj and showed himself to his people who collected on the riverbank,” she informs.

“All the buildings in the imperial part of the Red Fort were built as pavilions surrounded by gardens with fruit trees and fountains. There was the Khwabgah, or the emperor’s private chambers, the Rang Mahal, the Diwan-i-Khaas, the Hammam, and the living quarters of his entire family. Most of these structures are no longer there.”

Referring to the Diwan-i-Aam, where the emperor gave an audience and discussed administrative matters, Mukherji says that it is difficult to imagine what it was like in its heyday because most of its decorative elements are gone.

“They were looted at various times in history and the most recent and devastating was in the aftermath of 1857, when semi-precious stones from the walls were gouged out and entire marble panels were taken away. And the buildings were used for very inappropriate purposes — ranging from hospitals to prisons to canteens — after the British moved into the Fort and used it as a Garrison Fort,” she says and adds that what is seen today is the outcome of a conservation exercise that was conducted at the beginning of the 20th century.

“The conservation then could only be implemented in one part of the Fort and was done according to British cultural notions. So, it is difficult to get a sense of its original magnificence and spatial qualities. What we see today are the proportions of the building and its elements, and they still have a lot of grace and gravitas,” Mukherji avers.

Giving a vivid description of the original form of the buildings, she explains that what we see today are structures unclothed. “They had beautifully crafted awnings that were stretched out from them. So, the usable space was much more than just the building edge. Also, you would have had very richly worked clothes in brocade or velvet attached to the pavilions. Carpets were hung between the pillars, and at some places, there were railings of silver and gold; there was also extensive painted decoration on the walls,” she adds.

Mukherji refers to research that has shown that the buildings did not sit by themselves, but were connected in ingenious ways. “Today we see the Diwan-i-Am and Diwan-i-Khas, sitting all alone. But they would have had connecting colonnades that ran all around them. These were all removed, and they are in a sense, amputated. So again, you cannot get a sense of the magnificence because you no longer have their connections or the appropriate surroundings to view them properly,” she states.

Referring to the early conservation efforts, Mukherji maintains that these have been unable to restore the original level of construction, detail, and decoration. “It is difficult to reconcile the descriptions in the court histories with the way the buildings of the Fort stand today. The Fort’s grandeur had begun to decline in many ways soon after Shah Jahan, as Aurangzeb who succeeded him, after an initial period when he lived here, was later almost continuously away from Delhi in different parts of his empire. So, imperial patronage to the culture and arts declined substantially in Shahjahanabad till the beginning of the next century, when the Red Fort again became the seat of the empire,” she narrates. But by then the political power of the Mughals had begun to decline.

There were, however, some significant additions, which were made even later by different rulers, in the complex.

According to Mukherji, the most essential element in conserving anything is to first, understand its principles, and whether you are conserving it as merely a monument or something larger and intangible, like a cultural tradition.

“And I come back to the reason I wrote the book, which is that today, most people who visit the Red Fort, cannot comprehend why it is so important to conserve the Fort. Or that it could ever have been ‘the Most Magnificent palace in the East’. As I said, this is because there is so little of the original architecture, that remains; And what remains is viewed in such a reduced condition. The most important aspect of conservation, I believe, is to first comprehend for yourself as a conservation professional, what is most significant about what you are trying to conserve, and then communicate this understanding to everyone else — including those who live around the fort, visit, work within, or make policies,” she asserts.

“A characteristic feature in our traditional architecture is that open spaces are as necessary and important as built spaces. In the case of the Red Fort too, open spaces were an integral part of the buildings. Most of these open spaces — as also the gateways and the pavilions or the colonnades around or within them – do not exist today. So how do you present this characteristic feature? And make people aware of that knowledge? How do you communicate the fact that there was a large proportion of open spaces that do not exist in the same form anymore?” she asks. She advocates demarcating those spaces to at least indicate their spatial limits and dimensions. This can be done for the original courtyards, especially around areas such as the Diwan-i-Aam or the Naqqar Khana.

“It is impossible to recreate them physically in a three-dimensional form because of the inadequacy of records. However, since it is possible through geometrical studies and comparison of archival records, as I have done and shared in the book, one can certainly arrive at the plan dimensions of these forecourts and mark them out on site for visitors to appreciate the extent and size of these spaces,” she suggests.

Referring to the built structures within the complex, Mukherji claims that only a handful now remain. These are some of the imperial pavilions that have suffered a lot of degradation. “But they are the reason for the Fort to exist. The Fort was built in the first place because Shah Jahan wished to shift from Agra and reside in a new imperial palace and city. So, it is important to prioritise these original unique buildings above everything else,” she argues.

“The effort should be to indicate what they were when they were established. There is much that we can learn from them because if you look at the architecture that we practice today, it seems to be completely at variance with where we are. It is not in response to our geology, culture, or climate as it was in the past” she submits.

“It is also important not to see the Fort as frozen in time. It occupies a very important place in the popular imagination. If we can again get the Fort to function as a cultural centre for people in general – especially those who live in its immediate vicinity or proximity; if we can plan spaces for artisans and performances around and within it; if we can enliven it with social functions, museums and libraries that clarify its establishment and history; if we can make it a place which citizens can visit, learn from, participate in, we will be able to not only inform and engage but also truly conserve traditions, knowledge and skills — as well as the buildings themselves” she affirms.

“That way we will have a complex that is joined organically to the city around it, and we will be able to reinstate its social uses to an extent, opening up immense possibilities for its continued relevance to us in the future,” Mukherji asserts.

Listen to the full interview on the podcast Books and Us

On Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/episode/65OUy2KaINxs1ogKEALYkT?si=wzsAr6RoR0GZDSsiXVlfug

On Apple: https://podcasts.apple.com/in/podcast/books-and-us/id1688845897?i=1000672786161

*Senior journalist