[the_ad_placement id=”adsense-in-feed”]

Part 1: Entertainment is fine, but message and content too matter

By Rathin Das*

By Rathin Das*

Theatre is probably the most ancient, if not primitive, form of art — beginning from the cradle itself as the baby tries to imitate its mother, then father and then everybody else in the family and neighbourhood.

What is merely an imitation in the childhood — be it trying to utter a few fundamental words or to take the first baby steps — gradually transforms itself into theatre when a theme or story line is injected into the various sights and sounds recreated.

[the_ad_placement id=”content-placement-after-3rd-paragraph”]

Without a theme, all those sights and sounds — howsoever perfectly created — would remain mere imitations or just mimicry without a continuing value or shelf life, if we choose to speak in present-day management jargon.

Also see: Artist’s Gallery – Stunning timing and composition!

While sights and sounds provide treat for the human senses devoured through eyes and ears — in any form of entertainment, it is the induction of a theme and storyline which makes theatre very different from other forms of art. Cinema is only a superlative manifestation of the wholesome mixture of sights and sounds woven together into a theme. The celluloid version only uses technology to embellish the troika of sight, sound and theme of theatre and enables it to transgress the limits of time and space within the limited period the audience sits before the silver screen.

Technology thus provides enormous scope to cinema that theatre cannot because of its limitations of being confined to a specific time and space in front of a live audience. The theatre person cannot afford any mistake on stage as it would be noticed immediately by the audience sitting just a few feet away, but cinema artiste enjoys the privilege of a few retakes and also editing accompanied by series of backroom treatments at a later stage.

This is neither an allegation on the cinema people nor any effort to undermine the capabilities of the cine actors, but only a reminiscence of what the superstar of our times had said once.

In an interview to a newspaper, ‘Big B’ Amitabh Bachchan had commented that cinema is the only performing art which gives repeated chances to the actor to correct his mistakes before the final product reaches the audience. And, as you all know, Big B cannot be wrong in matters of theatre and cinema.

While cinema has all the advantages of big money and the technology it can buy, the theatre has to manage with meagre resources and limited accessibility.

But, then, theatre had always been in live contact with its original source — the people, who have sustained the various cultures through the ages. Theatre, thus, draws its inspiration from the people at every level of social and economic stratum even though it attains slight elitist connotations in some large urban centres.

Being rooted to the people, theatre also has an umbilical relationship with literature of the region and politics of the day. That is why themes of theatre in all ages reflected the prevailing mood of the times.

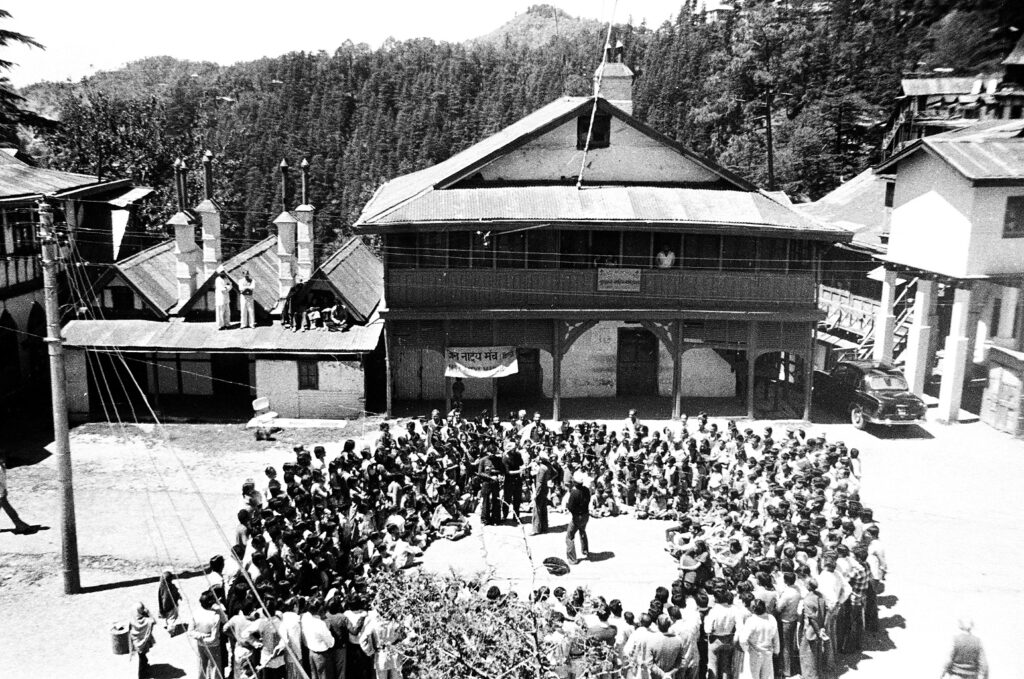

No wonder, thus, theatre in the pre-independence era revolved round the themes of freedom struggle, land rights, farmers’ ordeals, famines, unemployment and such other prevailing sentiments occupying the minds of the people then. Momentous plays on these themes in many parts of the country led to the birth of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) which did not remain just an organisation but gained the status of a movement by itself.

Though the IPTA’s themes and personalities were always on the wrong side of the British administrators by virtue of being anti-establishment in nature, people from this movement became a very rich source of experienced and creative manpower for the fledgling film industry in the post-Independence period.

The list of IPTA personalities who enriched Indian cinema is virtually endless but the stalwarts included Kaifi Azmi, Balraj Sahni, Salil Chaudhury, just to name a few. Their influence on Indian cinema continued for at least two to three decades before the whole paradigm of art and culture changed to an over-emphasis on entertainment because of its capacity to generate monetary profits for the owners of new cinematic technology.

With technology predominating cultural aspects and profit motives driving the cinema industry, it became a huge mass media beyond the imagination of the intelligentsia which had hitherto remained the foundation of theatre in its original form. A new element like glamour got associated with the films when the actors got transformed into stars and, consequently, became detached from the people began to be seen only as end consumers of the film industry.

As this process intensified, theatre became elitist in the big urban centres with only a handful of socially and economically influential people practising and patronising it merely for the ‘sake of art’.

But, then, ideological discontentment of people within the film industry about it being run only as a mass entertainment medium led to the eruption of what is generally called the ‘parallel cinema’, led by stalwarts like Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani, Mrinal Sen who chose to depict stark reality while legendary Satyajit Ray added the artistic flavour to similar real life stories and contemporary issues.

Even this genre of ‘parallel cinema’ had a limited appeal among the masses as they too had an elitist aura confined to the upper strata of society and the intelligentsia. This genre of ‘parallel’ cinema did contribute to slight ‘de-glamourisation’ of the films which also generated space for artistes with not so photogenic faces entering the arena in their own right as goods actors.

But, still, there was a cultural void for the common people like the factory worker, jobless youth or suburban vendor eking out a survival in urban centres, who were neither comfortable with much acclaimed and de-glamourised ‘parallel’ cinema nor could afford the tickets for the proscenium plays in the air-conditioned auditoriums far away from their living colonies which are virtually inaccessible by public transport late in the night when the shows end.

This void of people-oriented theatre became chronic in 1975, during the Emergency when civil liberties and freedom of expression were curtailed to such an extent that many theatre groups chose to suspend all their activities that could be remotely misconstrued as anti-establishment comments.

(To be concluded)

*Rathin Das is a senior journalist. He was actively associated with late Safdar Hashmi and his street theatre group Jana Natya Manch