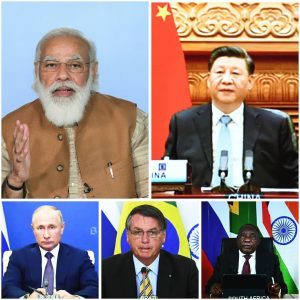

Analysis: 12th BRICS Summit 2020

By Deepak Parvatiyar

By Deepak Parvatiyar

It will only be apt to refer to the BRICS summits of 2015 and 2017 in particular to evaluate the just concluded 2020 summit in the right perspective. This is also important because of the prevailing situation when the entire world has been held hostage by the COVID19 virus, and there is an uneasy relationship too between India and China highlighted by the troops buildup along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Eastern Ladakh region. Hosted by Russia, the 12th BRICS summit was a virtual event against the backdrop of the Corona pandemic, and this obviously did not offer any opportunity of the customary one on one meetings between the leaders at the sidelines of such an event.

The 2015 BRICS summit at Ufa in Russia had marked the arrival of the New Development Bank (NDB) or the BRICS Bank, and the Contingent Reserves Arrangement (CRA). However, the summit had taken place when BRICS nations – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — were facing difficult times. Hence, the underlying theme of the summit that year was —“BRICS Partnership – A Powerful Factor of Global Development”. The very first paragraph of the Ufa Declaration had stressed on the discussions on “issues of common interest in respect of the international agenda as well as key priorities in respect of further strengthening and broadening our intra-BRICS cooperation”. This was significant because the very foundation of BRICS was based on the perception that the BRICS countries were the emerging dynamos of growth and hence a promising destination for investors. However, things were not looking that rosy and therefore there was ubiquitous stress on the word, ‘partnership’.

In the 2017 summit at Xiamen in China, when the stress was once again on ‘partnership’, with the theme being “BRICS: Stronger Partnership for a Brighter Future”, the situation was not much different than what it is today. Much akin to the the 2020 summit when two BRICS members, India and China, have been engaged in unprecedented troops build up along the Line of Actual Control and have witnessed the first fatalities on the Sino-India borders since 1975, the 2017 summit was held against the backdrop of the 73-day standoff between the two countries in the Doklam area near the Bhutan tri-junction, lying between China’s Chumbi Valley, Bhutan’s Ha Valley and India’s Sikkim state’s Nathang Valley, in the Himalayas. However, unlike the 2020 summit which was a comparatively smooth affair as it was hosted by Russia, the Doklam issue had cast a shadow over the very possibility of a successful summit in 2017 till the Indian Ministry of External Affairs issued a statement announcing “expeditious disengagement of border personnel at the face-off site at Doklam”, to ensure the standoff came to an end days before the BRICS summit, which was hosted by China then.

The Xiamen Declaration signed by the members during the summit had emphasised that BRICS members had “fostered the spirit of mutual respect and understanding, equality, solidarity, openness, inclusiveness and mutually beneficial cooperation” among themselves. The declaration had reiterated the shared desire for “peace, security, development and cooperation.” As for India, the inclusion of JeM and LeT in the Xiamen Joint declaration was a significant diplomatic success for India. This was the first time that China has signed such a statement which had named Pakistan-based terrorist groups, and could be termed as a smooth progression from the Goa summit of 2016 wherein the member states had “strongly” condemned terrorism in all its forms and manifestations and stressed that “there can be no justification whatsoever”. This was further carried forward to the 2019 BRICS summit that was held in Brazil’s capital, Brasilia. Here the members had decided to constitute five sub-working groups on counterterrorism in areas like terrorist financing, use of the internet for terrorism purposes, countering radicalisation and foreign terrorist fighters, even as the theme then was ‘Economic Growth for an Innovative Future’. Yet, without much progress seen on the ground, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi had to again raise the issue of terrorism in the 2020 summit, saying terrorism continued to be the biggest problem today. “We have to make sure that countries that shelter terrorists and support them are also held responsible,” he said, even as he expressed satisfaction that under Russia’s chairmanship BRICS’ Counter Terror Strategy has been give the final shape.

Also read:

The differences are far more pronounced within BRICS members in 2020. This year the theme chosen was – ‘BRICS Partnership for Global Stability, Shared Security and Innovative Growth’. But the fact is that each of the BRICS nations is facing their own internal crisis and the differences are disconcertingly distinct.

No doubt though that there is much headway since 2015 but much more is still required for BRICS members to emerge as a cohesive unit. The differences are far too varied and strained relationships particularly between India and China pose a great challenge before the BRICS grouping.

The BRICS summit 2020 was the second event this month after their virtual meeting at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, where Indian Prime Minister Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping came face to face again ever since the tensions broke between the two countries along the LAC. Like SCO, there was no bilateral meeting this time too because of the online nature of the summit. Yet these occasions did at least offer an opportunity for the two to share the web space together. But is that enough to break the ice between the two countries?

There is no surprise that respective geopolitical constraints did emerge as major impediment to deliberations at the just concluded BRICS summit which was the first ever virtual summit at the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic. There were different voices within the grouping even on the handling of the pandemic. While Chinese President Xi Jinping was all praise for the World Health Organisation’s role in handling the situation and stressed the need to support “WHO’s crucial leadership role in this endeavour”, Brazil’s far-right President Jair Bolsonaro criticised “the politicisation of the coronavirus and the alleged monopoly of knowledge on the part of the WHO”, and was of the view that the World Health Organisation (WHO) “urgently needed reform”.

Indian Prime Minister Modi too called for reforms in WHO as well as in United Nations Security Council where India eyes a permanent seat, International Monetary Fund, and World Trade Organisation.

Of course the role of WHO in handling the situation has come under scrutiny. The US administration decided to sever ties and terminate WHO funding and on July 6, 2020, officially notified UN Secretary-General António Guterres about its decision to withdraw from WHO membership. A New York Times report was more scathing in its attack – “The WHO’s staunchest defenders note that, by the nature of its constitution, it is beholden to the countries that finance it. And it is hardly the only international body bending to China’s might. But even many of its supporters have been frustrated by the organization’s secrecy, its public praise for China and its quiet concessions. Those decisions have indirectly helped Beijing to whitewash its early failures in handling the outbreak.”

Jinping used the BRICS forum to launch a veiled attack on the USA, as he said “Flouting rules and laws, treading the path of unilateralism and bullying, and withdrawing from international organisations and agreements run counter to the will of the general public and trample on the legitimate rights and dignity of all nations…We need to oppose interference in others’ internal affairs, as well as unilateral sanctions and long-arm jurisdiction.”

Such assertions and varied opinions, in any normal situation, could be called a regular feature of a multilateral forum. But in a charged atmosphere, its nuances can be interpreted differently. Modi said multilateralism today was passing through a difficult phase as the credibility of the institutions of global governance was being questioned. He asserted the need to reform the United Nations Security Council which he said was very essential. Bolsonaro, on his part, launched an attack on multilateral forums. As it is, he is facing the heat back home and is also threatened by the US President-elect Joe Biden – whom Bolsonaro has still not congratulated on his victory – that Brazil might face “significant economic consequences” if the deforestation of the Amazon continued. The Brazilian President is facing criticism over the alarming figures of fires and deforested areas in the Amazon, 60% of which is in Brazilian territory. Targeted by conservationists who accuse Bolsonaro of openly promoting illegal mining, ranching and logging, he used BRICS forum to declare – “In the next few days, we will reveal the names of the countries that have illegally imported timber from the Amazon.”

Yet, undoubtedly in the last few five years, the member countries, as Russian President Vladimir Putin noted, have increased cooperation in science, technology and innovation, but the complexities of the issues transcending BRICS are far more grave and could be reflected in China’s President Xi Jinping’s views that today international environment was extremely turbulent considering the evident trend of “de-globalization processes and prevailing economic uncertainty”.

Jinping himself is in the eye of the storm following his aggression in South China Sea, Hong Kong, India. As mentioned, over a lakh soldiers from both India and China are eyeballing each other along the LAC and this is likely to continue even during the harsh winter season when the temperature in those regions come down to such lows as minus 30-40 degree Celsius! In September, Taiwan too had called for a global coalition against China, fearing a “real possibility of war”.

It may be noted that in the 2018 BRICS summit at Johannesburg in South Africa, the members had talked about strengthening multilateralism and the rule of international relations, and to promote a fair, just, equitable, democratic and representative international order. “We recommit our support for multilateralism and the central role of the United Nations in international affairs and uphold fair, just and equitable international order based on the purposes and principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations, respect for international law, promoting democracy and the rule of law in international relations, and to address common traditional and non-traditional security challenges,” the BRICS members had declared then.

However, this very idea of multilateralism faces a challenge as was mentioned above. But there are quite a few positives too. Jinping’s offer to work with India and other member countries on COVID vaccines could be seen in this light. “As we speak, Chinese companies are working with their Russian and Brazilian partners on phase-III clinical trials of vaccines, and we are prepared to have cooperation with South Africa and India as well…We will actively consider providing vaccines to BRICS countries where there is a need,” Jinping said at the summit and reports suggest that soon Indian and Chinese officials will sit together to work out the modalities of cooperation to develop COVID-19 vaccine.

The biggest strength of BRICS is that today its members have emerged as the driving engine of global economy with 25% share (US$21 trillion) in global GDP. Modi sounded more optimistic of the prospects of BRICS mutual institutions and systems – such as BRICS Inter-Bank Cooperation Mechanism, New Development Bank, Contingent Reserve Arrangement and Customs Cooperation – facilitating effective contribution in post-COVID global recovery. Russian President Putin too, attached significance to the direct contribution of the BRICS countries toward a comprehensive package of G20 measures aimed at overcoming the negative consequences of the pandemic. President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa pointed out that the New Development Bank serving BRICS nations had approved US$4 billion in COVID emergency assistance and appeared likely to add $10 billion more in COVID assistance and economic recovery funds. South Africa had received $1 billion of the original funding. Ramaphosa, who is also the current African Union chairman, even expressed his gratefulness to the BRICS partners “for the solidarity we have received from our BRICS partners, both through bilateral assistance and support for our continental response”.

Statistics show that over the past five years, intra-BRICS exports grew by 45% and the share of intra-BRICS exports in total BRICS international trade increased from 7.7% to 10%. The GDP of the five countries also grew faster than global and G7 GDP at an average annual rate of 5.31% according to the IMF.

Not ignoring the fact that BRICS nations also constitute 42% of the world’s population, there indeed is ample scope for scaling up mutual trade between BRICS countries. But this can be done only when the BRICS nations overcome the prevailing trust deficit and hostility.

Very good article

Very indepth analysis.

Good read