As far as exposure to climate stressors is concerned, female-headed households are more likely than male-headed households to reside in areas where temperatures are rising quickly and where floods occur frequently. This is likely since increased exposure to climate stressors is a driver of male outmigration, leaving more women behind as household heads in these areas. Female-headed households are marginally less likely than male-headed households to reside in areas that have been exposed to droughts and heat stress.

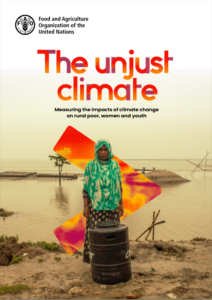

According to a 2024 report published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) titled The Unjust Climate – Measuring the impact of climate change on rural poor, women and youth, female-headed households have, on average, older heads, lower levels of education and fewer household members; in addition, they cultivate less land and invest less in agricultural activities than male-headed households. They also own significantly fewer livestock units than male-headed households. The lack of productive resources and human capital acts as a significant barrier to climate adaptation and economic inclusion for these households.

According to a 2024 report published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) titled The Unjust Climate – Measuring the impact of climate change on rural poor, women and youth, female-headed households have, on average, older heads, lower levels of education and fewer household members; in addition, they cultivate less land and invest less in agricultural activities than male-headed households. They also own significantly fewer livestock units than male-headed households. The lack of productive resources and human capital acts as a significant barrier to climate adaptation and economic inclusion for these households.

These constraints are reflected in differences in the adoption of climate-adaptive agricultural practices. The data show that plots managed by women are less likely to be irrigated or receive soil amendments, such as organic fertilizers. Female farmers are also less likely to have formal documentation for their land and to own agricultural machinery, suggesting that they are more dependent on manual labour for agricultural production.

As a result of these numerous constraints, female-headed households tend to earn significantly less than male-headed households from agricultural sources and generate less total crop value. For this reason, they havea lower total household income than male-headed households.

The per adult equivalent amount earned by female-headed households from off-farm income sources is similar to that for male-headed households. This result is likely tied to female employment in the agrifood system, which is a major employer of women and constitutes a more important source of livelihood for women than for men (FAO, 2023a). However, employment in the agrifood system tends to be highly sensitive to climate variability. Off-farm income is therefore a potential source of vulnerability for female-headed households – although it also offers opportunities to strengthen their climate resilience.

Looking at gender-specific labour allocations, women are less likely to be employed and tend to work fewer hours than men. This suggests that despite the importance of off-farm employment in the incomes of female-headed households, their access to such employment is more constrained than that of men, and their work tends to be more informal and sporadic.

Incidentally, the report finds that young households face many of the same challenges as poor and female-headed households in terms of access to productive resources. (Households are classified as young if the household head is 34 years old or younger, while prime-aged households are those headed by people who are 35 to 64 years old. Households with a head older than 64 years are coded as senior-headed households).

Also read: Effects of climate change on rural income vary with gender

Young households are, on average, less educated, have fewer household members, cultivate less land, invest less in agriculture and own fewer livestock units than households headed by an older person. They are also less likely to access social protection programmes, have titles to their land or own agricultural machinery. These factors are important contributors to the climate vulnerability of young households.

At the level of agricultural plots, the data show that young farmers are more likely than older farmers to adopt labour-intensive adaptive practices, such as using soil and water conservation structures, but also to have less diverse cropping systems and use less organic fertilizer.

It may also be mentioned that a poor household is a household that belongs to the bottom 25th percentile of a multidimensional poverty index distribution.

Many key socioeconomic differences between poor and non-poor households make poor households considerably more sensitive to climate change and less able to adapt than non-poor rural households. On average, poor rural households have older heads, are more likely to be female-headed, have less formal education, cultivate less land and spend less per hectare under cultivation than non-poor households.

Despite owning less land and investing less in agriculture, poor households derive a significantly larger share of their total income from agriculture than non-poor households. This heavy reliance on agriculture for their livelihoods is an important source of their vulnerability. Adaptation investments in agriculture to reduce the climate vulnerability of the rural poor are therefore of crucial importance.

Poor households are less likely to access extension services, own agricultural machinery or have documented ownership of their land, which all act as important barriers to the adoption of climate-adaptive agricultural practices. Poor households earn significantly less income from off-farm sources than non-poor households. This reflects the challenges they face in terms of accessing such income sources, as well as the low wages they earn.

At the same time, poor households are more likely to access social protection programmes and own slightly more livestock units. These are likely to be important mechanisms that poor households use to cope with the adverse effects of climate change on their well-being.

In terms of exposure to extreme weather events, there are small but statically significant differences between poor and non-poor households in terms of drought, heat stress and flood exposure, as well as long-term temperature rises.

The report finds that climate vulnerability and adaptive capacities are influenced by the socioeconomic resources available to a person or household, as well as by their level of exposure to different climate stressors. It mentions that the recognition of poverty as a multidimensional problem has given rise to the development of various methodologies to capture the multiple deprivations (beyond monetary deprivation) that simultaneously contribute to the experience of poverty.

– global bihari bureau