A view of Shanghai, China

Geneva: The COVID‑19 pandemic has posed an unprecedented shock to China’s economy. Besides inflicting human costs, it has had a major impact on output, trade, and employment. At the beginning of 2020, economic growth fell to its lowest level in 40 years: between the last quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020, growth fell by almost 13 percentage points, from 5.8% to -6.8%. Apart from financial services and information technology, all sectors were severely hit. Over 100 million workers were directly affected by the pandemic, by being put on unpaid leave in retention schemes or reduced-work programmes, exiting the labour market, or becoming unemployed. In May 2020, the Government abandoned the announcement of the annual GDP target for the first time in more than 25 years due to factors that are difficult to predict, such as the coronavirus pandemic and uncertainties around trade.

Fuelled by a middle class that has been increasing both in number and in average income, consumption played an important role in sustaining economic growth until 2019, although household saving rates remained high. Over the same period, investment growth slowed. Starting in mid-2020, China’s economy began to recover from the pandemic, as economic activity normalized. The recovery was mainly driven by public investment and international trade, whereas private consumption remained sluggish in the presence of continued uncertainties; the authorities consider that the recovery in private consumption gained momentum in recent months, as observed in retail sales of consumer goods.

Swift fiscal and monetary policy reactions (Section 1.2.2) helped mitigate the economic impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic and prepare for the recovery. GDP growth was 2.3% in 2020, which made China the only G-20 economy with a positive growth rate that year. Growth is projected to be over 6% in 2021, as economic activities continue to normalize and further domestic outbreaks of COVID–19 remain under control.

But as a result of the Government’s stabilizing measures, financial stability risks may have increased, warned a World Trade Organization (WTO) report based on the eighth review of the trade policies and practices of China that took place on October 20 and 22, 2021, today. The basis for the review is a report by the WTO Secretariat and a report by the Government of China.

Moreover, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), risks of the projection are tilted to the downside, with a possible resurgence of the pandemic and a tightening of financial conditions.

China’s current account surplus contracted between 2016 and 2018, but grew again in 2019, to USD 102.9 billion. Available information for 2020 indicates a widening of the surplus, to USD 273.9 billion (1.9% of GDP), while for 2021, the authorities predict a narrowing of the current account surplus. The financial account (excluding reserve assets) posted a strong deficit in 2015, a surplus between 2016 and 2019, and a deficit in 2020. Direct investment was in surplus in all recent years except for 2016. The portfolio investment account was in deficit until 2016 and has posted a surplus since 2017.

China’s merchandise trade surplus declined between 2016 and 2018, which was a major driver of its narrowing current account surplus. In 2019 and 2020, the trade surplus grew again. China’s balance of trade in services has traditionally posted a deficit, which grew between 2015 and 2018, but fell in 2019 and 2020.

The country’s merchandise imports increased sharply between 2016 and 2018, it fell in 2019 and 2020.

China’s simple average applied most-favoured nation (MFN) rate too decreased from 9.3% in 2017 to 7.1% in 2021, with tariff-rate reductions in nearly all product categories. The percentage of tariff lines bearing rates higher than 15% (international tariff peaks) was 4.5% in 2021, significantly lower than the 13.9% in 2017.

Between 2018 and mid-April 2021, China was involved in 10 trade disputes as a complainant and 11 as a respondent. It was also involved as a third party in 38 disputes brought to the Dispute Settlement Body during the same period.

Moreover, China’s outward FDI, after lagging behind for many years, overtook inward FDI in 2015. It peaked in 2016 and has fallen sharply every year since. The Annual foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows into China continued to grow between 2016 and 2019, although at a much slower pace than in previous periods.

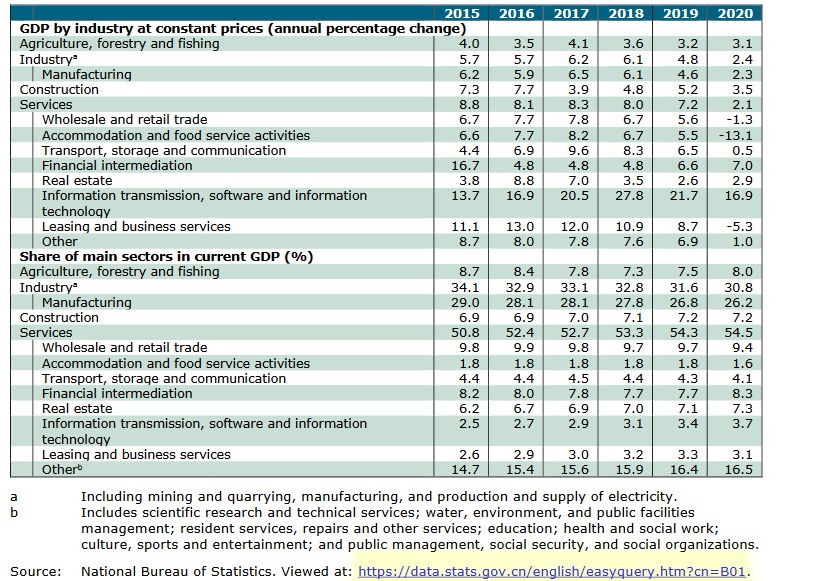

GDP by Sector, 2015-2020

With regard to the sectoral composition of China’s GDP, the long–term structural change away from industry towards services continued during the review period. The contribution of agriculture to GDP fell from 8.7% in 2015 to 7.3% in 2018, before slightly climbing again during the pandemic. While the share of industry fell, it remains very high by international comparison, at around 31%. Services now make up 55% of China’s GDP, up from 51% in 2015. The fastest–growing service sectors during the review period include information transmission, software, and information.

Against the background of dampening of domestic demand and weaker exports, partly resulting from trade tensions, the authorities resorted to various stimulus measures during the review period, involving taxes, access to credit, and infrastructure investment; however, according to an OECD study, the stimulus may increase corporate sector indebtedness and, more generally, reverse progress in the deleveraging of state–owned enterprises (SOEs).

– global bihari bureau