-By Mahadev Desai*

-By Mahadev Desai*

(April 30, 1938)

“Badshah Khan,” someone told us, “is hardly to be found at home…”

Last week I was able, at long last, to pay the visit to the Frontier that we have been longing for all these years. Gandhiji would have gone there in early April, had it not been for the visit to Orissa and the prolonged stay in Bengal. And as he failed, he thought it well to send me for a few days to meet the two Brothers, and I was grateful for the opportunity.

As the train winds its way through the hilly country from Rawalpindi, the scene around is bleak and bare and desolate. Within a couple of hours one passes through Taxila, the famous ancient city with a storied past. Can this ancient city of Buddhist relics have been a treeless waste even in those days? The mind refuses to think so. I had no time to alight at Taxila and see the past in the ancient monuments. As the train passes through a mountain tunnel one sights on emerging from it something like an Asokan pillar on a hill. But it might well be the monument of a bloody victory of a much later day than the peace edict of that Buddhist sovereign. Within a little while the train crosses the Punjab boundary and enters the Frontier where the river at Attock separates the two boundaries. Even here the country has the same unrelieved desolate look, though the river was swollen with turbid mountain water and rushed in simple, unadorned, impetuous majesty reminiscent of the temperament of the Pathan whose country one enters there. Not until one arrives at Nowshera one sees any vegetation. But now the scene changes and lovely gardens of lemon and pomegranate and peach come into view almost right up to Peshawar.

Also read: History Recalled: A feast for the eyes

As this time I had gone by myself and not with Gandhiji, I had a better opportunity of seeing men and things. Quite a number of friends were good enough to pay me a visit and acquaint me with their view of the state of things. I had ample opportunities of seeing the Prime Minister Dr. Khan Saheb and other Ministers as also men of various shades and schools of thought. With its population of 92 per cent of Mussalmans and 8 per cent Hindus, Sikhs and others, the Province is beset with a task that no other province is faced with. For a vast majority to keep a minority contented should not be a difficult task, and it would appear that but for the situation in the Punjab and in other parts of the country Dr. Khan Saheb’s task would be less difficult.

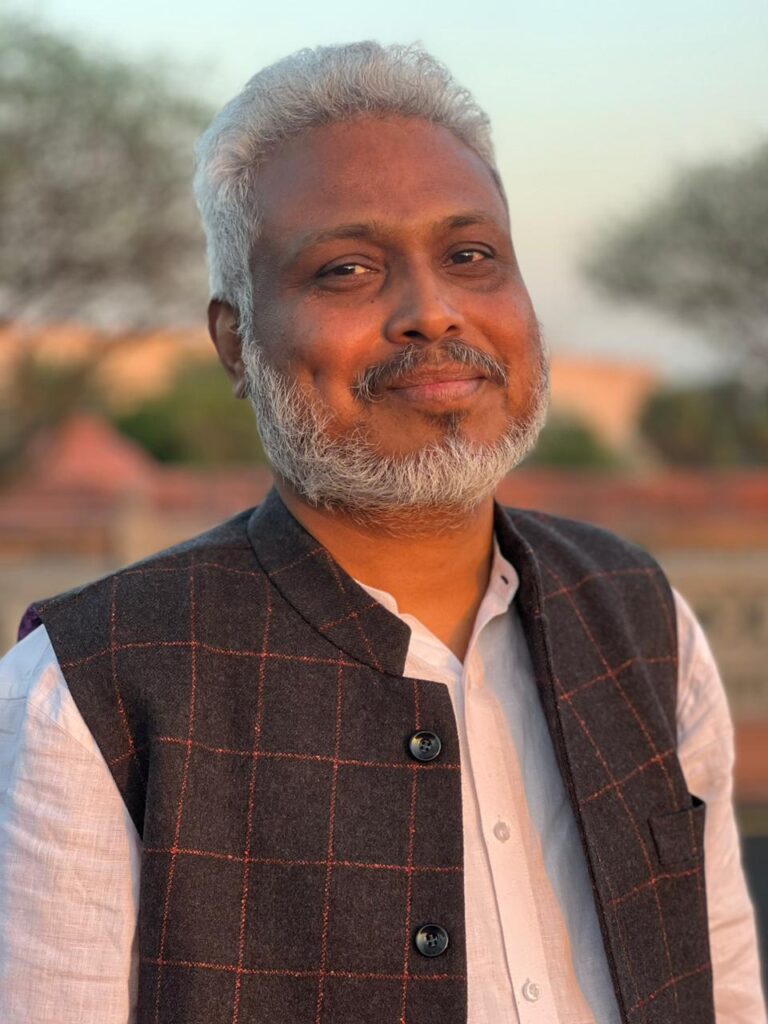

Badshah Khan

Having seen the elder brother, I drove with him to their home where the younger brother Khan Saheb Abdul Gaffar Khan was staying. He was not at Utmanzai. “Badshah Khan,” someone told us, “is hardly to be found at home. He is wandering from village to village.” And it was with some difficulty that we found him in a neighbouring village. He was doing his afternoon namaz, and we were told to wait until he returned from the masjid. There were a number of friends and relations at home, but whilst they had not gone for their namaz, Khan Saheb, who never misses one of the five daily namazes, had gone to the masjid. Ever since 1921 he is popularly known as Badshah Khan amongst his people who revere him as their king.

I had heard about his fast and I requested him to tell me all about it, which he willingly did. “There was a death in a certain village,” he said, “and the relatives of the deceased were very keen on my saying the prayers before the body was carried to the graveyard. I was in a hurry to leave for another village and so I suggested that the prayers should be said in the nearest masjid. The Maulvis in the village, however, insisted that the prayers should be said in the maqbarra which was some distance from the village. I pleaded with them and said that I had been to Macca and Medina and there was no objection to saying the funeral prayers in a masjid. But the Maulvis maintained that the practice was against the shariat and that I was speaking in ignorance. We yielded. On our way back to the village the Maulvis began calling me all kinds of names. This enraged the people and they fell upon the Maulvis. Some of the Khudai Khidmatgars who were there on the spot intervened and rescued the Maulvis. This was a laudable act, but then they proceeded to do what was not their business. The Maulvis had knives and spears on them, and the Khudai Khidmatgars wanted to wrest these from them, lest they should use them against the people. I was walking a little distance in front of these people, and as soon as I learnt that there was a little fracas I rushed to the spot and found the Khudai Khidmatgars in the act of wresting the weapons. I told them that this was highly improper and that as I could not punish them I must punish myself, and declared a complete fast for three days. This had an electric effect. Everyone there was shocked. With tears they appealed to me to give up the fast and offered to take the punishment upon themselves. I explained to them that it was no use their doing so, that they must meet together and resolve never to repeat the thing, and left for Peshawar.”

The fast was not the Islamic roza, but a complete fast with permission to take water and salt. The Pathans, who are hospitable to a fault and would not let a guest go away without making him eat something, could not bear a strict fast of this kind. They met in various places, and Khan Saheb was having numerous resolutions assuring him that the mistake would not be repeated.

A Pathan Village

We then set out on Khan Saheb’s horse tonga for villages in the east, driving through vast expanses of a country of fields smiling with wheat and barley and punctuated with lovely gardens. At every mile or two the Khan Saheb would drive into a village, introduce me to the Khan, tell me something about his history, and start for another. I saw them there in their simple mud huts — walls and roof both of mud. Many of them had their revolvers and leather- belts full of cartridges. The Khan Saheb said that the Pathan women observe no purdah (excepting the aristocratic families), but I saw no woman’s face. As for the folks in the village there is a wonderful spirit of democracy. The meanest servant in the house and the humblest field labourer comes and greets you and offers to shake hands with you. Every child in the village gives the Badshah Khan his or her greeting, and the Badshah must return the greeting. “Kher Ali,” they say. “Teri Mash, Teri Mash,” replies the Khan Saheb. The first greeting corresponds to “How do you do the return greeting means literally, “I hope you are not tired ”( i. e. I hope you are free from all worries).

Cleanliness is hardly a -strong feature of these villages, and the animals and the poultry do not help to improve it. In the evening we walk out through the fields along footpaths and canal-ridges. “How smiling is this land,” says the Khan Saheb. “We have bumper crops. There are plenty of fruits. Fruits which in your part you prize and pay fancy prices for, grow here in abundance and go to waste. There is a quality about the grass we grow here that makes the cow’s milk particularly rich. A cow gives as much as 14 seers a day. And yet there is plenty of unemployment, and these folks do not get enough to eat.” And yet their hospitality is lavish. “We Pathans would waste any amount of money over entertaining guests, but if you ask them to contribute any hard cash, they would not do so. They are temperamentally incapable of giving any cash.”

Everywhere they inquire when Gandhiji is coming. I twit them about their revolvers. “This suits ill with your talk of Gandhiji and Khan Saheb,” I say to them. “No,” they reply. “When we go out with them we need not take them.” “But why must you take them even when alone?” I ask. “There are what we call blood feuds, and one never knows when one may be attacked. But Badshah they will not touch,” they say and laugh a hearty laugh.

I am offered my tea in the proper style, and I am surprised to see the beautiful tea-set in front of me. The Khan Saheb explains: “Tea has penetrated the poorest hut in the poorest hamlet, and even the field labourer will not go to the field without having a drink of his decoction. The Khans drink it in proper style.”

There have been deaths in two villages. We go there. At one place we sit solemnly, the Khan Saheb makes a call for a brief prayer for the deceased, then some other caller does the same thing, and the visit comes to an end. At the other place, there is a large assemblage of callers. The call for prayer is made twice, thrice, four times. Then the silence is broken by the Khan Saheb who speaks to them on the value of the revival of handicrafts, being content with whatever the village can produce and so on. There is a friend there in outland¬ish dress. His American accent betrays his American education. He had been to California for the study of agricultural industries and is interested in bee-keeping. “There are five hundred Pathans in California,” he says.

Many of the Pathans are clad in khadi. They are Khudai Khidmatgars. They wear red shirts while on duty, otherwise like the Khan Saheb they wear a shirt and pyjama of ashen gray. Khan Saheb has set the fashion and it has become popular. Before the crowd of callers breaks up one of the hosts insists on their staying to eat. I ask the Khan Saheb whether it is a custom to give something like a caste-dinner after death. “No,” he says. “But the bereaved family is supposed to do no cooking, and so some relative of the family undertakes to do the cooking. He feeds the family and also the guests who break bread with the bereaved and sympathize with them in their sorrow. The practice was to go on doing this for days together. I protested against it and now it is fast dying out. The Maulvis are interested in bolstering up all kinds of usages and superstitions, and they swear at me because I am now working for their abolition.”

– to continue

*Mahadev Desai was an eminent freedom fighter and Mahatma Gandhi’s personal secretary; article courtesy his grandson, Nachiketa Desai.