The destruction of cotton weaving in India was an accomplished fact

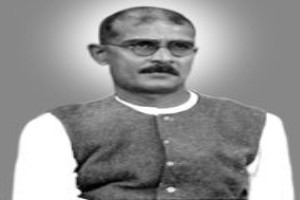

By Mahadev H. Desai*

By Mahadev H. Desai*

(This article was published on July 26, 1921 in Bombay Chronicle)

Mr. Whitmore, one of the witnesses before an Inquiry that took place about 1833 and cited by Mr. Thornton, said that in 1814 the total amount of manufactured cotton exported from England was 818,203 yards, in 1828 it was 43,500,000 yards; that the value in 1814 was 190,000 pounds – in 1794 it was hardly 154 pounds – and in 1828, notwithstanding a fall in prices, it was 1,900,000 pounds. Mr. Thornton remarks: “He did not state that this increased exportation had driven the manufacturers of India to starvation, and brought ruin to districts and cities previously flourishing and happy; nor did he state the difference in the quality of the English and Indian cotton goods vastly exceeded the difference in price.”

Also read: History Recalled: How India’s industry was ruined – 4

But I shall not multiply these extracts which are bound to curdle any true Indian’s blood. Suffice it to say that at the time of the 1840 inquiry the destruction of cotton weaving in India was an accomplished fact, as Mr. Brocklehurst with cool complacence said that silk was the “last of the expiring manufactures in India” and several European witnesses urged that it should not be oppressed with the duty of 20 per cent in favour of the British manufacturer, but without avail. Lord Ellenborough recommended equalising of duties on the import of cotton between Britain and India as the Indian cotton manufactures had died out but did not do so as regards silk. There is a pathetic interest about the following questions and answers between the Committee and Mr. Melville (who was once Secretary of the East India Company). It reminds one of a jury trying to make sure that a certain body is really dead by various questions and cross-questions:-

“Native manufactures have been superseded by British?” Melville was asked.

“Yes, in great measure.”

“Since what period?”

“I think principally since 1814.”

“The displacement of Indian manufactures by British is such that India is now dependent mainly for its supply of those articles on British manufactures?”

“I think so.”

“Has the displacement of the labour of native manufactures at all been compensated by any increase in the produce of articles of the first necessity, or raw produce?”

“The export of raw produce from India has increased since she ceased largely to export manufactures; but I am not prepared to say in what proportion.”

It is beyond the purpose of this article to enter into the history of the rise and growth of the mill industry in India, and how efforts have been made to arrest its growth. It may be said without fear of contradiction that the mill industry has done nothing to rehabilitate the artisans and the weavers whom Britain’s rapacity had ruined. Nor need one describe here the other process by which India has been drained to its last drop of blood.

It is only necessary for us to remember that spinning and weaving were once our national industries, that the spinning-wheel and the hand-loom were universal, and that they fell a prey to Britain’s rapacity. Inasmuch as we were willing or unwilling partners in that sin. Awakened India today calls for atonement. And there can be no better atonement than pledging ourselves to producing our own cloth and using nothing but that cloth. India’s resolve consists in nothing more than a refusal to wear foreign cloth. It would have been open to her to declare an exclusive boycott of British cloth if she had thought of retaliation. At any rate it is absurd for those who have pursued a policy of rapacity for years to brand any measure, on the part of India, for self-preservation as punishment. But India is distinctly not out for punishment. If her atonement, if her resolve to sacrifice luxuries and to use what coarse cloth it can produce, hits Lancashire hard, it is no one’s fault. Acts of purity have a natural tendency to embarrass evildoers.

But we are concerned with our duty. An Indian merchant came the other day to Mr. Gandhi, saying that he had been dealing with English merchants for the last hundred years and that it would be act of disloyalty on his part to stop dealings with him. This mentality is but an index of the depths of self-forgetfulness to which we have sunk. The subtle narcotic, that the selfishness of the British trader has administered to us for all these years has benumbed our sense of self-respect and killed the consciousness that we were going deeper into disloyalty to our nation. Nearly a century ago Macaulay vauntingly said, “we shall never consent to administer pousta to a whole community to stupefy and paralyse a great people whom God has committed to our charge for the wretched purpose of rendering them more amenable to our control.” But it is clear that nowhere was such a dose more successfully administered. But by the grace of God an awakening has come, and if we have not forgotten our history, if we are not false to those that fell a prey to the tyrannical commercial policy of a nation of traders, we shall count no cost too great, we shall not listen to the whispering of satan who is busy in season and out of season to stimulate our selfishness and thwart noble purpose.

– Concluded

Mahadev Desai was an eminent freedom fighter and Mahatma Gandhi’s personal secretary; article courtesy his grandson, Nachiketa Desai.

From tomorrow: History Recalled: Towards an ideal Zamindari by Mahadev Desai