[the_ad_placement id=”adsense-in-feed”]

By Alok Shukla*

By Alok Shukla*

Is the crisis of Coronavirus (Covid-19) being turned into an opportunity for mining companies? At least from the plans of the government for the coal mining sector, it would seem so.

As the covid-19 (coronavirus) crisis deepened, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had urged that the crisis should be turned into an opportunity. Gradually, it took the form of what he termed as “Atmanirbhar Bharat” (or Self-reliant India). Filled with this sense of “Atmanirbharta”, the Minister of State for Coal tweeted “UNLEASHING COAL, New Hope for Aatmanirbhar Bharat”. Through this, the government announced auction of 41 coal blocks for commercial use on June 18. In these times of crisis, when the world economy is reeling under recession, and corporates are demanding economic stimulus for themselves, auctioning of the precious mineral wealth is a bit startling. It also raises a series of questions – Whose self-reliance? Which hope? And opportunities for whom?

[the_ad_placement id=”content-placement-after-3rd-paragraph”]

Certainly, this move does not seem related to the “atmanirbharta” of the tribal community as they will have to face the brunt of displacement, and their problems are only bound to increase. Nor is this “atmnirbharta” linked to India’s coal needs, as these mines are being auctioned for commercial mining, which has nothing to do with the country’s needs. Government data and Coal India Limited’s (CIL) “Vision – 2030” has already highlighted that its production plans, along with the currently allocated mines, are enough to satisfy India’s coal needs for the next 10 years. CIL’s workers unions have already opposed this move which is likely to adversely affect CIL’s health and continuity.

Also read:

हमारी कोयला नीति भाग 1 : जल, जंगल, जंगलवासी व जंगली जानवरों को बचाने की ज़रुरत

हमारी कोयला नीति भाग 2: क्या सोचता है एक आम आदमी

(Google translator facility is available on this news portal to read in languages of your choice)

Similarly, it is also difficult to find “hope” for a “new India” in this step, as the auction of these mines is bound to result in indiscriminate and reckless destruction of the country’s dense forests and valuable natural wealth. The need to safeguard ecologically important areas for future generations, i.e. new India, as well as keep them as “strategic reserves” and last resort to meet the energy requirements during national emergency, has already been spoken about extensively. The Government has already marked such regions as “inviolate” due to their ecological importance and rich biodiversity which should not be destroyed under any circumstances.

It can also not be seen as an “opportunity” for the development of the low-income states, as state governments have no role in this process. The allocation process has significantly disempowered state government and reduced them into “permit office”, which is contrary to the spirit of the 2014 Supreme Court order. The Chief Minister of Jharkhand, Hemant Soren has already written a letter opposing this move. Congress ruled opposition states have also expressed concerns and reservations regarding this.

Under these circumstances, the rationale behind the current auction seems unclear. Further, most of the companies do not have financial resources to participate in the auctions and the demand for energy is continuously falling. It is puzzling how government expects to get large number of bidders for these coal blocks in an economic downturn, when it had failed to do so at comparatively better times.

Disaster Capitalism?

These questions point us towards Naomi Klein’s conception of “Disaster Capitalism”. A professor at Rutgers University in the US, she had argued that governments exploit the opportunities presented by disasters to pass difficult policies to promote neo-liberalism, which would otherwise face stiff opposition in normal times. However, it is difficult to apply even this concept to the current auction of coal blocks – it does not appear to bring in any long-term liberalization policies. Instead, it seeks to monetize the mineral wealth, in the largest ever auctions till date, amidst poor market conditions, which is only bound to end up in significant losses to the public exchequer.

Perhaps, a new terminology is required to understand this. It might be more appropriate to call it “Disaster Cronyism” since it seeks to give away India’s valuable wealth, without concern of public interest and with limited scrutiny, at throwaway prices, to select corporate houses who have the appetite to participate in these difficult times. In light of this, this “opportunity” of pandemic, can be seen as the “hope” for select corporate houses, which can then form the basis of “atmnirbharta” of the political parties.

Failed Auctions In The Past

When we talk of auctions, it is important to remember the experiences of similar auctions conducted in the past. In 2014, the Supreme Court had cancelled the allotment of nearly all the coal blocks. Subsequently, the Modi Government had claimed about hugely successful auctions that yielded trillions of rupees, and compensated for the losses in the Coalgate case. However, merely a first look at the data tells a completely different story. It appears that the past auctions were a complete failure.

Since 2015, the Central Government has been making efforts to auction coal mines from time to time. Over the last 5 years, the Government has attempted to auction more than 80 coal blocks at different points of time. However, of these, only 31 could be successfully auctioned. In fact, the 4th-8th tranche of the coal auctions had to be cancelled, as the government could not find the minimum number of bidders for most of the blocks.

The disastrous performance of the auctions can also be seen that even among the 31 auctioned blocks, the allotment of 8 had to be cancelled as the allottees expressed their inability to start operations. Out of the remaining 23, mining has started in only 12 mines even today after five years. Of these, most blocks (10) are the same mines which were operational before 2014.

Reasons For Past Failure Of Auctions

There are several reasons for the failure of the auction process and disinterest of bidders –

1) There is no need for coal on such a scale in the country as mentioned by CEA, Coal India Limited vision-2030, and other analysts, 2) Most of the companies in the sector are either bankrupt or facing significant economic distress, 3) Most of the coal blocks kept in the auction did not have environment and forest clearances, which significantly increased the risks for the bidder, 4) There were multiple irregularities in the auction processes, as also highlighted by the CAG report in 2017. Some of these issues culminated in the cancellation of some blocks on grounds of suspected collusion, like Tara, Gare Pelma –IV / 2 & 3, etc.

One of the other key reasons for the failure of the auction was that the government opened a back door for selected companies through MDO model where risks were low and profits were higher. Several questions have already been raised on the transparency and fairness of allocation through this route. Nevertheless, out of 58 mines allotted through this route, only 9 mines have been started out of which 4 were already operational before 2014.

The central government had argued that auctioning of coal mines will benefit state government and they add 3.35 lakh crores in their revenues. However, information revealed under RTI shows that auctioned mines have generated only 5.68 thousand crores by 2019. One of the primary issues behind it that most of auctioned coal block has remain non-operational due to various reasons, and have not generated any revenue.

Hence, it is imperative to ask the question – why is the government not focused on the already allotted 60 mines which are yet to be operational (11 – through auction and 49 – allotment – MDO way)? Why are new auctions needed, when the already allotted mines are not operational?

The real math behind the situation is linked to the countries coal requirements and the existing capabilities of the coal mining companies. In reality, the question is linked to the end-use provisions, which require the usage of coal for specified end-use. When there is no need, what is the need for end-use projects, and consequently, the need for commissioning of mines or new auctions?

Is Commercial Mining Policy An Opportunity For The Corporates?

Despite failing to find minimum bidders in previous auctions, why does the government suddenly want to auction 80 coal blocks in one go, that too under these circumstances? Which companies have resources to participate in these auctions, at this time of economic crisis? Who will benefit from lesser participation in the current bidding process? Or in the name of self-reliant India, is there a conspiracy to hand over this valuable wealth of the country to select corporate groups at throwaway price?

To find the answers to these questions, we have to go back a little. When the Covid crisis in the world was taking the form of epidemic, government was not only busy with “Namaste Trump” and illegal trade of MLAs in Madhya Pradesh, but was paving a way for corporate loot.

Prior to the lock-down, the Modi government had relaxed the norms of coal block allocation through the “Mineral Laws (Amendment) Act 2020” and removed end-use requirements for coal block allocation to private companies. The bill had been passed in parliament without major discussion as the opposition, perhaps, failed to grasp the import of its key provisions.

Four important provisions were introduced by the Modi government through this amendment: First, it abolished the obligation to use coal only in the national interest, allowing, the use of coal blocks for commercial profit. Second, the requirement of minimum number of bidders was reduced from 4 to 2. This would reduce competition among companies, which also means lower bidding prices. Third, in the auction, the basis of price was changed to “per ton” while the reserve price was kept at merely 4 percent of the revenue share. This change in pricing implies that not only is it quite low, but the pricing is very difficult to estimate and monitor. Fourth, it introduced the provision of prospecting-cum-mining licenses, making its regulation more difficult. In the process, it also reduced several rights of the state governments in the auction/allocation process.

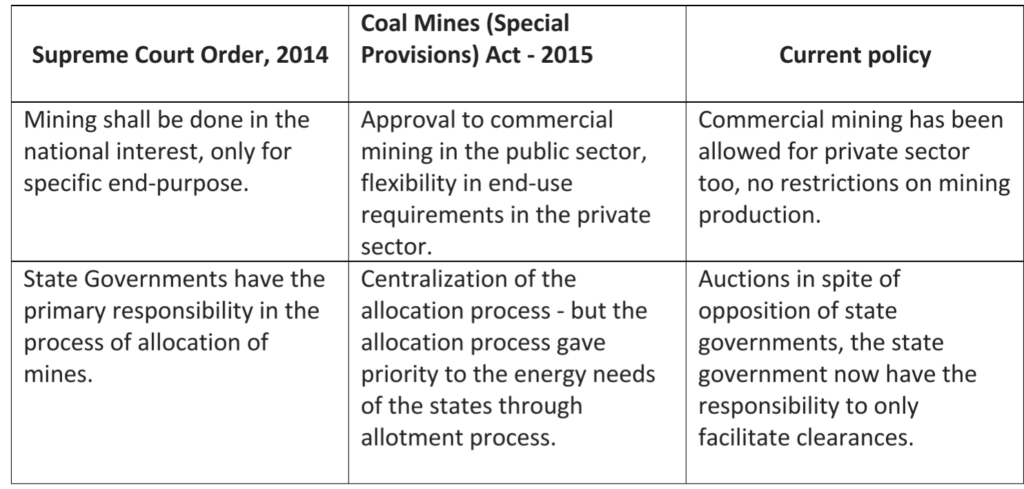

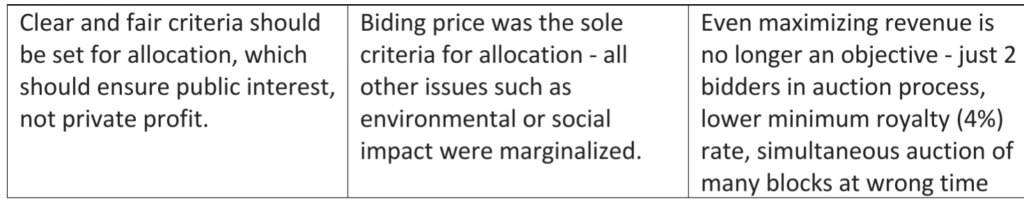

The Current Auction Completely Undermines The Spirit Of The 2014 Supreme Court Order

Through these amendments, it is clear that the companies that did not show any interest in the auction in the last 5 years, can use this golden opportunity to acquire coal blocks and indulge in blatant profiteering. It is also a great opportunity to give the MDO-allocation scam a legal cover. This policy has also relaxed the mining processes so that companies can export coal, produce arbitrarily, and hoard coal when not needed.

Evidently, this current policy and auction process is completely contrary to the spirit of the order given in Supreme Court’s Coal Gate. Although, the Coal Mines (Special Provisions) Act 2015, already attempted to reverse several key provisions, which witnessed widespread opposition at the time, both within and outside Parliament. Now this new policy has been crafted in such a manner, that even the essence of the original order of the Supreme Court has not survived.

Impending Destruction Of Dense Forest Areas And Displacement Of Tribals

It is clear that, the new policy and auction process has completely ignored objectives like nation-building, and public interest. The biggest brunt of this policy and the latest round of auctions will be faced by the ecology and adivasi forest-dwelling population.

Several mines, included in the auction, are located in India’s densest forests and ecologically important regions. Moreover, majority of these mines are in Fifth Schedule Areas where people have special rights under PESA Act 1996 and Forest Rights Act 2006. However past experiences points towards inevitable destruction at large scale after the allocation of these mines.

This issue can be better understood by taking the example of the Hasdeo Aranya region in Chhattisgarh. This region is one of the most densely forested, biodiversity rich, and habitat of elephants and other wild animals. It is important for the ecology of, not only Chhattisgarh, but entire central India. The Government of India had declared the region as “No Go” regions in 2010 due to its ecological sensitivity (such regions are less than 10% of coal reserves of entire country). Even the current government considers most (18 out of 20) coal blocks in the Hasdeo Aranya region as “inviolate”. In fact, Hasdeo Aranya has the highest number of coal blocks designated as “inviolate”, in entire country as per the assessment of current government. Despite this, 6 coal blocks have been included in the auction list for commercial mining in addition to the 7 coal blocks have already been allocated to public companies.

In such a situation, it is certain that the entire region, also known as the “lungs of Chhattisgarh”, will be destroyed, which can never be replenished. Additionally, the Gram Sabhas of the region have been continuously opposing mining by passing resolutions under PESA and FRA. They have also protested against the auction / allocation by letters to the Prime Minister, Coal Minister, Chief Minister, etc. The villagers have been on strikes, fasts, and protests for the last 5 years. But, is anyone willing to listen to the voices from the forest?

– with Priyashu Gupta*

*Alok Shukla is a Chhattisgarh based social and environmental activist & Priyanshu Gupta is a Ph.D scholar at IIM, Calcutta. The views published are their own.

[the_ad_placement id=”sidebar-feed”]