Lens with a heart

Living A Caged Life

–By Sudharak Olwe*

–By Sudharak Olwe*

24th December 2018: Dehri on Sonne, Rohtas District

Ghusia Kallan, Vikramganj, Halkhor, Dome Community

As you enter Meenadevi’s semi-pucca house, you would find a parrot named Mithu squeaking and acknowledging her presence as she taps its cage. It was quite symbolic as she might even see her life’s reflection in that caged parrot. A tiny uneven passage leads to small open foyer which has a hand pump surrounded with utensils, chulha with cow-dung cakes. The adjacent wall has a huge crack which seems fragile. There were tattered, washed out woollen clothes hanging on the string. There is a small kitchen with bare minimum utensils, gas and food items. A closer look at the house and one could sense the life of penury Meenadevi and her family is living but that doesn’t stop her from laughing or playing with her parrot.

Also read: Photo Essay: Including the Excluded – Part 4

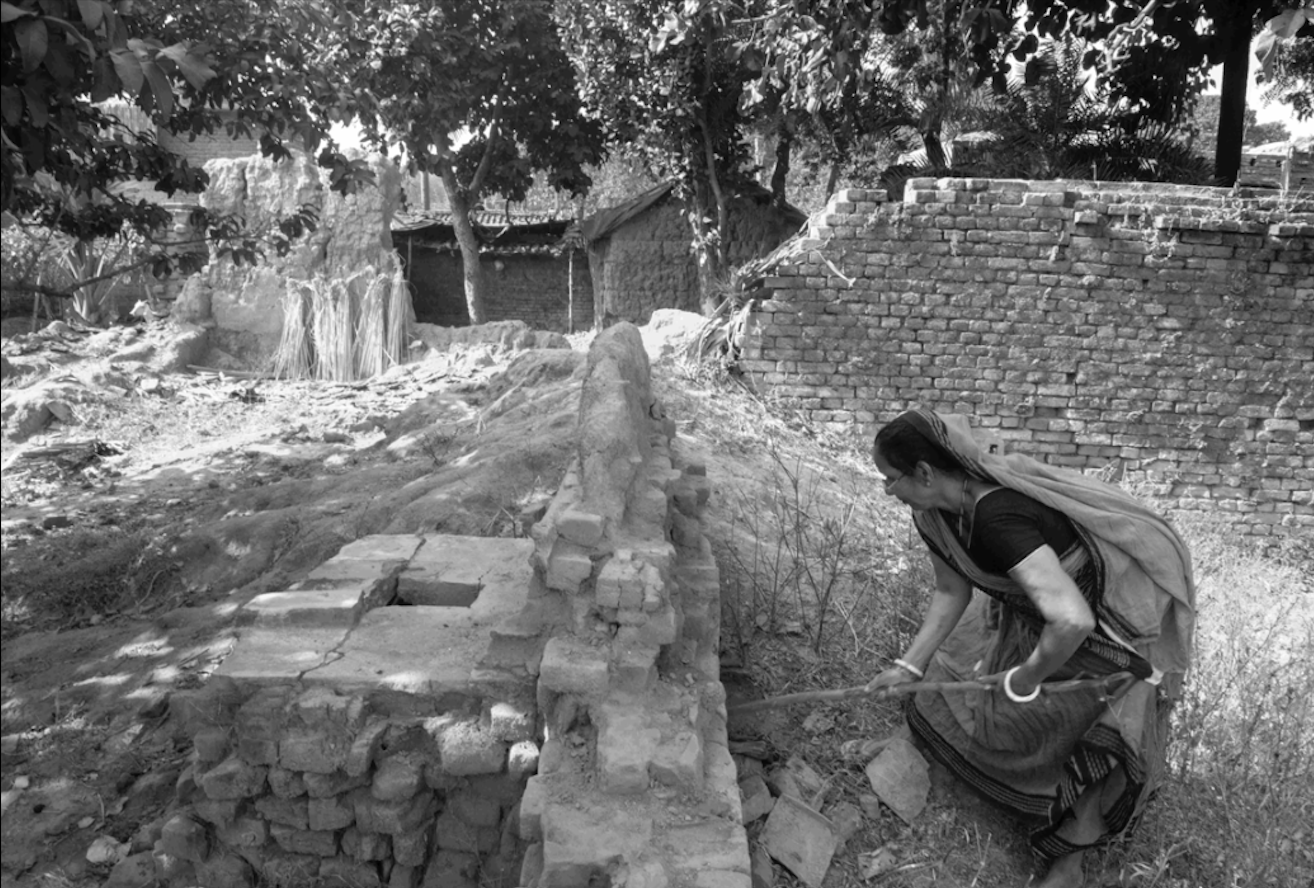

It’s one thing to empathise with and another to actually live a caged life of manual scavenger. When you see a 58-year-old Meenadevi cleaning one of the last few dry latrines present in Ghusia Kalan village in Vikramganj Tehsil of Bihar’s Rohtas district, you can’t help but feel angered and helpless over her pathetic situation. “Initially, I used to feel nauseated. I wasn’t ready and felt ashamed to work because of the stigma attached to it. But now I’m used to the foul smells. Poverty leaves you with no option… With the amount of discrimination we face, what else can we do to feed our stomach? Give us another job and we will leave this one immediately,” she says.

In a slightly torn and worn-out saree, Meenadevi walks about 2 kms from her house into the village where most of the Muslim families still demand manual scavengers for cleaning their dry latrines. Apart from a few Muslim households, she has been working with the local hospital since 2012. However, she hasn’t been paid since because the Hospital authorities keep telling her that “they are operating at a loss.” Meanwhile, she is hoping that someday, she would be paid the whole amount. The locality she takes us has several mud and semi-pucca houses lining the path and an open ground which was now turned into a small dump yard. She enters the Khatun household where she has been working for over 25 years and takes us to the spot where dry latrine is situated. “I’m thinking of quitting now. There are hardly any dry latrines left and since people have begun building flush toilets, they no longer need us. Besides, I’m getting old to invest in this kind of hard labour,” Meenadevi says while we accompany her to the fields.

Under the blazing sun, she walks for about four kms back and forth making her way through the fields to throw the waste in a manure pit.

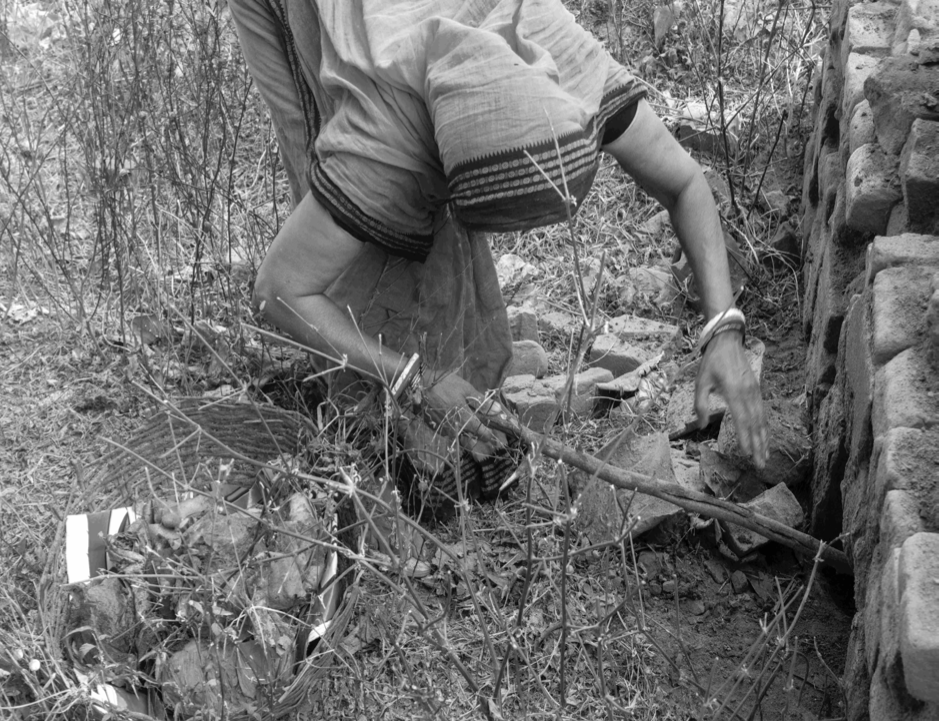

Quite swiftly, she breaks a long dry branch of the tree lying on the ground and uses it to collect the waste lying from behind the open vent near the drop hole of the latrine.

Once that’s done, she picks up the now dried waste and human excreta using cardboard pads, shoves it in the partly broken bamboo basket and heads to dispose it off to a nearby field. Munni Khatun, the owner of the house, then pours water from a distance so that Meenadevi can wash her hands.

From earning Rs 2 per house when she began with her mother-in-law almost 25 years ago, she now gets Rs 50. Meenadevi and her mother-in-law, both from the Dom community, used to work for majority of the houses in the same neighbourhood, when almost all them had dry latrines. “My mother-in-law died doing this job. She used to carry the excreta and sewage in tin cans. I did the same. Now, we don’t use tin cans. Nonetheless, the same fate awaits me,” Meenadevi said with a melancholic voice revealing years of pain and suffering.

*Sudharak Olwe is an Indian Social Documentary Photographer. In 2016, he was conferred the Padma Shri, India’s 4th Highest Civilian Award by the President of India, in recognition of his valuable and tireless work.