Photo courtesy Press Council of India's official website

By Nava Thakuria*

By Nava Thakuria*

Guwahati: Even though the Indian media fraternity observes National Press Day on November 16, commemorating the day when the Press Council of India (PCI) started functioning, the quasi-judicial body still has no authority over news channels and digital media outlets. For long PCI has been dubbed as “toothless”, and it should be an occasion for the practising media persons to introspect seriously over their noble profession, where it has actually been heading to in the post-Covid-19 era.

Despite its many limitations, since its inception and functioning, the PCI to its credit still continues to symbolize a free and responsible press in the largest democracy in the world. Among all press or media councils, functioning in various countries, the PCI is recognized as a unique entity that exercises authority over the media and also safeguards the independence of the press.

Under the Press Council Act 1965, various relevant functions such as helping newspapers to maintain their independence and building up a code of conduct for newspapers and journalists in accordance with high professional standards are being authorized for the PCI. Undoubtedly, the sole aim of journalism should be the service to humanity.

Lately, newspapers have witnessed a drastic fall in their circulation. The newspaper industry is actually struggling for survival after the invasion of satellite television channels and digital outlets.

However, till the last century, newspapers dominated the media scenario. In northeast India, since the days of Arunodoi (1846), there were publication of a good number of morning dailies in various languages. Prior to the pandemic, Guwahati supported the publication of around 30 dailies with hundreds of periodicals. But the endless corruption among many editors and a visibly low space for the valued readers/audience/viewers to make their official points even in need have steadily ruined the sacred profession. Once the quality internet became available to the common people, a large number of social media users started questioning professional journalists and the professional media persons were seemingly not ready for that. With a number of print editors rejecting social media by terming it a nuisance helped deteriorate the situation.

In the recent past, altogether three Guwahati-based television journalists (who started careers as print journalists) were named and shamed in social media as being beneficiaries of the National Register of Citizens updation scam in Assam. At least one prominent filmmaker identified a television talk show host in his Facebook post that the scribe had grabbed a huge amount of money which was due for the temporary workers (data entry operators) in the process. The accused television journalist aggressively supported the draft NRC in various official appearances (reasons best known to him), even though it still faces many pertinent questions ranging from its cut-off year (1971) to the inclusion of millions of illegal Bangladeshi migrants. In a public comment, the scribe in question even compared those who support 1951 as the cut-off year to identify the infiltrators in Assam (as it is done across the country) as “idiots”. Recently, a senior print journalist in his post claimed that the accused scribe even spent money in the local press club election to get an executive committee of his choice. Need not mention that the concerned electoral exercise was a visible expensive affair to the common city residents as well. A large number of leading print journalists were denied their membership, so they could not participate in the election, either as candidates or voters. Rumours were spread that a powerful politician was behind their mission, which turned false later. In both cases, when thousands of alternate media users accused the journalist and press club authority of corruption and mismanagement, they remained silent.

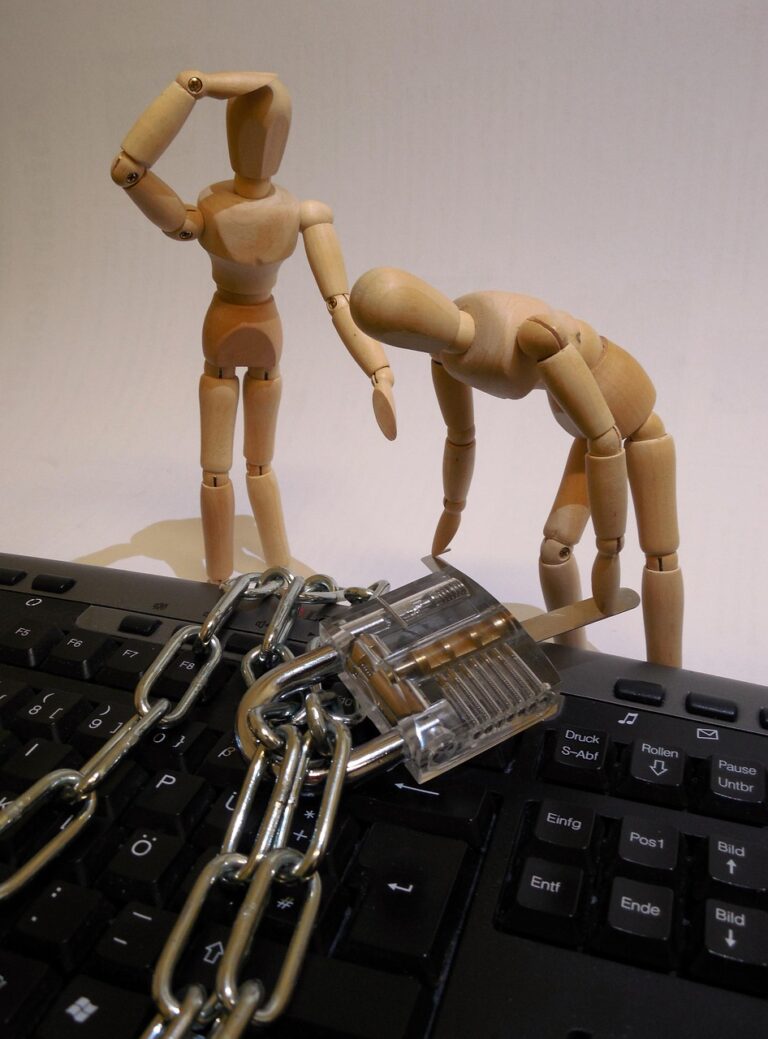

Months back, a list of beneficiaries from the coal mafia went viral on social media where some journalists and press associations were named. Amazingly, they did not make a response. PCI should have intervened in all those matters for the sake of India’s media fraternity, but it has limited authority. Thus, the existence of the statutory body has been denied by dishonest media persons. What more we are waiting for?

*Senior Journalist. The views expressed are personal.

Sadly, even the PCI has little power as it has no penal powers and its orders largely remain unimplimented.

The TV news channels also have a regulatory body but it’s recommendations are forwarded to the I & B Ministry which may or may not implement them.

Thus, the social media has a free run unless it runs foul to the Government