By Mahadev Desai*

By Mahadev Desai*

(January 22, 1938)

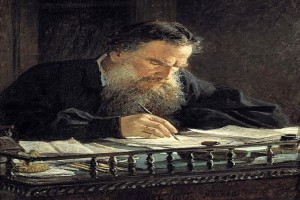

TOLSTOY’S RECOLLECTIONS AND ESSAYS

These have been published for the first time in the World’s Classics of the Oxford University Press. The book contains, among other things bearing the impress of Tolstoy’s “rocklike integrity and simplicity” whose effect is invariably tonic and invigorating, Tolstoy’s famous ‘Letter to a Hindu’ was published for the first time by Gandhiji in 1909. In his introduction Gandhiji described himself as “a humble follower of that great teacher whom I have long looked upon as one of my guides”, and described the method of non-violence as “the divine law of love” which admits of no exception.

Also read:

In this ‘Letter to a Hindu’ Tolstoy mercilessly exposes the three justifications of violence — the religious one based on the divine right of kings, the scientific one based on the theory of the survival of the fittest, and the political one based on the right of the majority to suppress some whom they consider undesirable. Therein, too, he analysed the causes of our slavery and said: “When the Indians complain that the English have enslaved them, it is as if drunkards complained that the spirit-dealers who have settled among them have enslaved them. You tell them that they might give up drinking, but they reply that they are so accustomed to it that they cannot abstain, and that they must have alcohol to keep up their own or other nations. If the people of India are enslaved by violence it is only because they themselves live and have lived by violence, and do not recognize the eternal law of love inherent in humanity.”

And then follows a passage reminiscent of his brother in spirit Thoreau: “As soon as men live en¬tirely in accord with the law of love, and hold aloof from all participation in violence — as soon as this happens, not only will hundreds be unable to enslave millions, but not even millions will be able to enslave a single individual. Do not resist the evil-door and take no part in doing so, either in the violent deeds of the administration, in the law courts, the collection of taxes, or above all in soldiering, and no one in the world will be able to enslave you.” A plea which sounds as fresh today as it was when it was made, and has yet to be lived by every pacifist. This is followed by a number of letters between Tolstoy and Gandhiji, in one of which Tolstoy describes the Satyagraha in South Africa as work which “seems to us to be at the end of the earth, is yet in the centre of our interest and supplies the most weighty practical proof” of the law of love.

The volume contains some of the fruits of Tolstoy’s mature thinking and ripe experience. “Why do men stupefy themselves?” must be read by every prohibitionist as also by every winebibber and tobacco-smoker. To this question Tolstoy gives the only true and spiritual reply, viz. “The cause of the world-wide consumption of hashish, opium, wine and tobacco, lies not in the taste, nor in any pleasure, recreation, or mirth they afford, but simply in man’s need to hide from himself the demands of conscience.” He exposes effectively the plea for “moderate” drinking and “moderate” smoking, and proves that “if the use of stupefiers in large occasional doses stifles man’s conscience, their regular use must have a like effect whether they are taken in large or small doses.” “If I do not smoke I cannot write, is what is usually said, and what Tolstoy him-self once used to say. “But,” asks Tolstoy, “what does it really mean? It means either that you have nothing to write, or that what you wish to write has not yet matured in your consciousness but is only beginning dimly to present itself to you, and the appraising critic within, when not stupefied with tobacco, tells you so. If you did not smoke you would either abandon what you have begun, or you would wait until your thought has cleared itself in your mind; you would try to penetrate into what presents itself dimly to you, would consider the objections that offer them- selves, and would turn all your attention to the elucidation of the thought. But you smoke, the critic within you is stupefied, and the hindrance to your work is removed.”

And here is a passage reminiscent of the 16th Chapter of the Bhagwadgita :

“When observing his own life, a man may often notice in himself two different beings — the one is blind and physical, the other sees and is spiritual. The blind animal being eats, drinks, rests, sleeps, propagates add moves, like a wound- up machine. The seeing, spiritual being that is bound up with the animal does nothing of itself but only appraises the activity of the animal being; coinciding with it when approving its activity, and diverging from it when disapproving.”

And then take this passage:

“People drink and smoke, not casually, not from dullness, not to cheer themselves up, not because it is pleasant, but in order to drown the voice of conscience in themselves. And in that case how terrible must be the consequences! Think that a building would be like erected by people who did not use a straight plumb-rule to get the walls perpendicular, nor right-angled squares to get the corners correct, but used a soft rule which would bend to suit all irregularities in the walls, and a square that expanded to fit any angle, acute or obstuse. Yet, thanks to stupefaction, that is just what is being done in life. Life does not accord with conscience, so conscience is being made to bend to life.”

In these days of reading all that is modem and latest in the world of art, it may not be unprofitable to turn every now and then to Tolstoy to get over the stupefaction which much of the things going by the name of “modern” creates in one’s life.

*Mahadev Desai was an eminent freedom fighter and Mahatma Gandhi’s personal secretary; article courtesy his grandson, Nachiketa Desai.