Geneva: The resurgence of global economic activity in the first half of 2021 lifted merchandise trade above its pre-pandemic peak, leading WTO economists to upgrade their forecasts for trade in 2021 and 2022.

The WTO is now predicting global merchandise trade volume growth of 10.8% in 2021—up from 8.0% forecasted in March—followed by a 4.7% rise in 2022 (Table 1). Growth should moderate as merchandise trade approaches its pre-pandemic long-run trend. Supply-side issues such as semiconductor scarcity and port backlogs may strain supply chains and weigh on trade in particular areas, but they are unlikely to have large impacts on global aggregates. The biggest downside risks come from the pandemic itself.

Behind the strong overall trade increase, however, there is significant divergence across countries, with some developing regions falling well short of the global average.

“Trade has been a critical tool in combatting the pandemic, and this strong growth underscores how important trade will be in underpinning the global economic recovery,” Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala said. “But inequitable access to vaccines is exacerbating economic divergence across regions. The longer vaccine inequity is allowed to persist, the greater the chance that even more dangerous variants of COVID-19 will emerge, setting back the health and economic progress we have made to date.”

“As we approach the 12th Ministerial Conference, members must come together and agree on a strong WTO response to the pandemic, which would provide a foundation for more rapid vaccine production and equitable distribution. This is necessary to sustain the global economic recovery. Vaccine policy is economic policy – and trade policy,” she said.

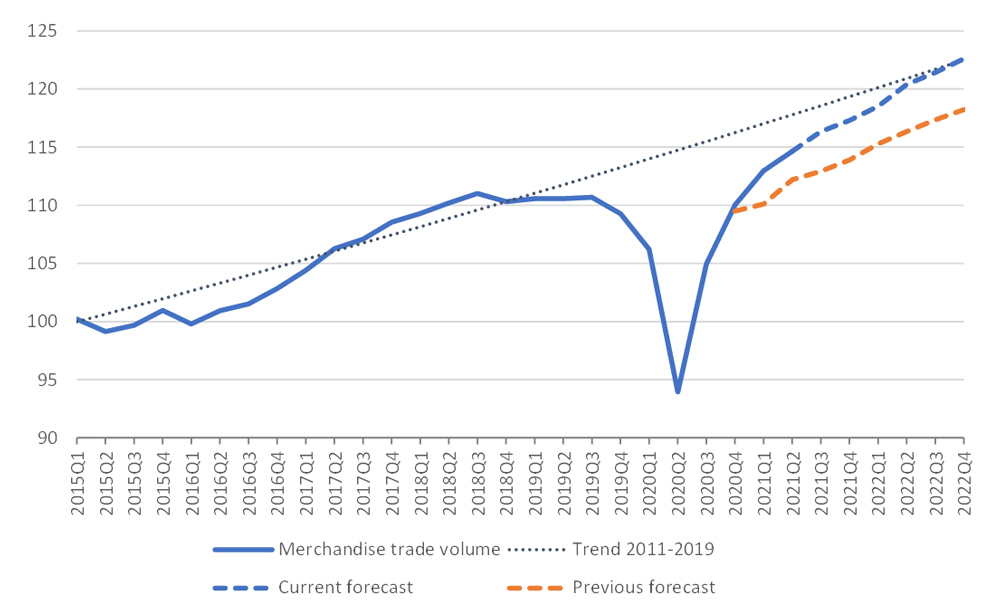

The large annual growth rate for merchandise trade volume in 2021 is mostly a reflection of the previous year’s slump, which bottomed out in the second quarter of 2020. Due to a lower base, year-on-year growth in the second quarter of 2021 was 22.0%, but the figure is projected to fall to 10.9% in the third quarter and 6.6% in the fourth quarter, in part because of the rapid recovery in trade in the last two quarters of 2020 (Chart 1). Reaching the forecast for 2021 only requires quarter-on-quarter growth to average 0.8% per quarter in the second half of this year, equivalent to an annualized rate of 3.1%.

Chart 1: World merchandise trade volume, 2015Q1-2022Q4

Index, 2015=100

The trajectory of the current merchandise trade forecast in Chart 1 is close to the upside scenario discussed in the WTO’s most recent forecast of 31 March. That scenario depended on a number of assumptions, including an acceleration in the production and dissemination of COVID-19 vaccines. More than 6 billion doses have been produced and administered worldwide. This is a remarkable achievement, but unfortunately still insufficient, because of sharp differences in access across countries. To date, only 2.2% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Failure to vaccinate in all countries against COVID-19 has led to a two- track recovery, with slower growth in countries with limited access to vaccines, which are frequently those that had the least fiscal space to support businesses and households. This divergence creates space for the emergence and spread of new, potentially vaccine-evading forms of the virus, which could result in the reimposition of health-related controls that reduce economic activity.

Trade volume growth is set to be accompanied by market-weighted GDP growth of 5.3% in 2021 and 4.1% in 2022 (revised up from 5.1% and 3.8% previously). GDP growth has been spurred on by strong monetary and fiscal policy support, and by the resumption of economic activity in countries that have been able to deploy COVID-19 vaccines at scale.

In the years before the global financial crisis (1990-2007), world merchandise trade grew around twice as fast as world GDP at market exchange rates, but subsequently slowed to about the same rate on average. The current trade projections imply that the ratio of trade growth to GDP growth will rise to 2.0:1 in 2021 before falling back to 1.1:1 in 2022. If the forecast is realized, this would indicate that the pandemic will not have had a fundamental structural impact on the relationship between world trade and income.

Risks to the forecast remain on the downside, but the relative importance of those risks is difficult to gauge. They include spikes in inflation, longer port delays, higher shipping rates, and extended shortages of semiconductors, with supply side disruptions being exacerbated by the rapid and unexpectedly strong recovery of demand in advanced and many emerging economies. The pandemic itself presents potentially even bigger risks to world trade and output, particularly if more deadly variants were to emerge. The highly contagious Delta variant has already prompted governments to reinstate some containment measures.

The recent upticks in inflation are probably temporary, driven by supply-side shocks affecting certain sectors in specific economies balanced against the unexpectedly strong recovery in demand. However, if inflationary expectations do become entrenched, central banks may feel the need to tighten policy early. This could create negative spill-overs, which would eventually hit trade flows. The period after the pandemic may see some periods of volatility as monetary policy normalizes and as governments shift to more sustainable fiscal policies.

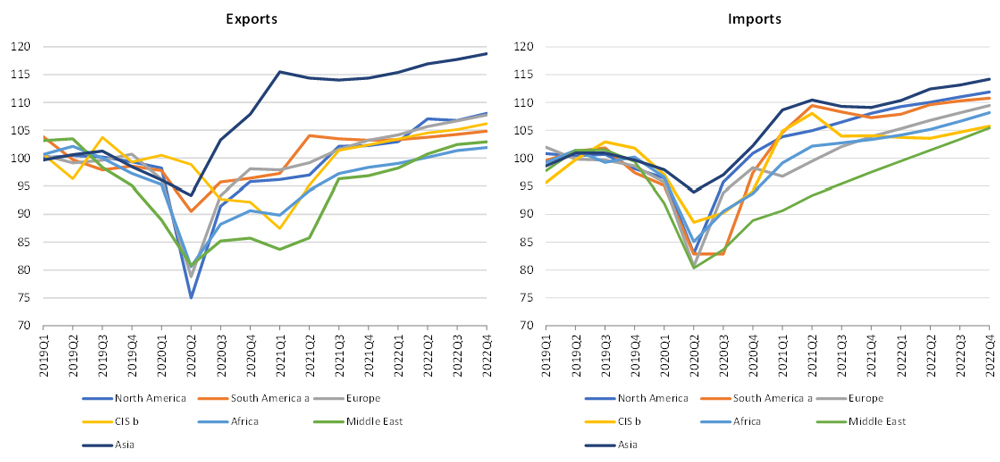

Overall, the trade recovery continues to diverge by region. In particular, the Middle East, South America and Africa look set to have the weakest recoveries on the export side, while the Middle East, the Commonwealth of Independent States, and Africa will have the slowest recoveries on the import side.

Chart 2 shows quarterly growth in the volume of merchandise trade by region since 2019, the last full year before the COVID-19 pandemic. Because the depth of the recession in 2020 differed from one region to the next, 12-month year-on-year growth rates do not illustrate the crisis’s impact on each region’s trajectory as effectively as cumulative projected trade growth over the three years between 2019 and the end of 2022, visible in the divergence between the lines for each region.

If the current forecast is realized, by the final quarter of 2022 Asia’s merchandise imports will be 14.2% higher than they were in 2019. Over the same period, imports will have risen by 11.9% in North America, 10.8% in South and Central America, 9.4% in Europe, 8.2% in Africa, 5.7% in the Commonwealth of Independent States and 5.4% in the Middle East. Asia’s exports will have grown 18.8% over that period, while all other regions will have recorded more modest increases: North America (8.0%), Europe (7.8%), CIS (6.2%), South America (4.8%), the Middle East (2.9%) and Africa (1.9%).

It appears that regions with oil-reliant export bases suffered large declines in both merchandise exports and imports during the 2020 recession, and that these losses have since been only partly recovered. South America’s relatively strong import recovery also reflects base effects from recessions in some of the region’s key economies in 2019.

Chart 2: Merchandise exports and imports by region, 2019Q1-2022Q4

Volume index, 2019=100

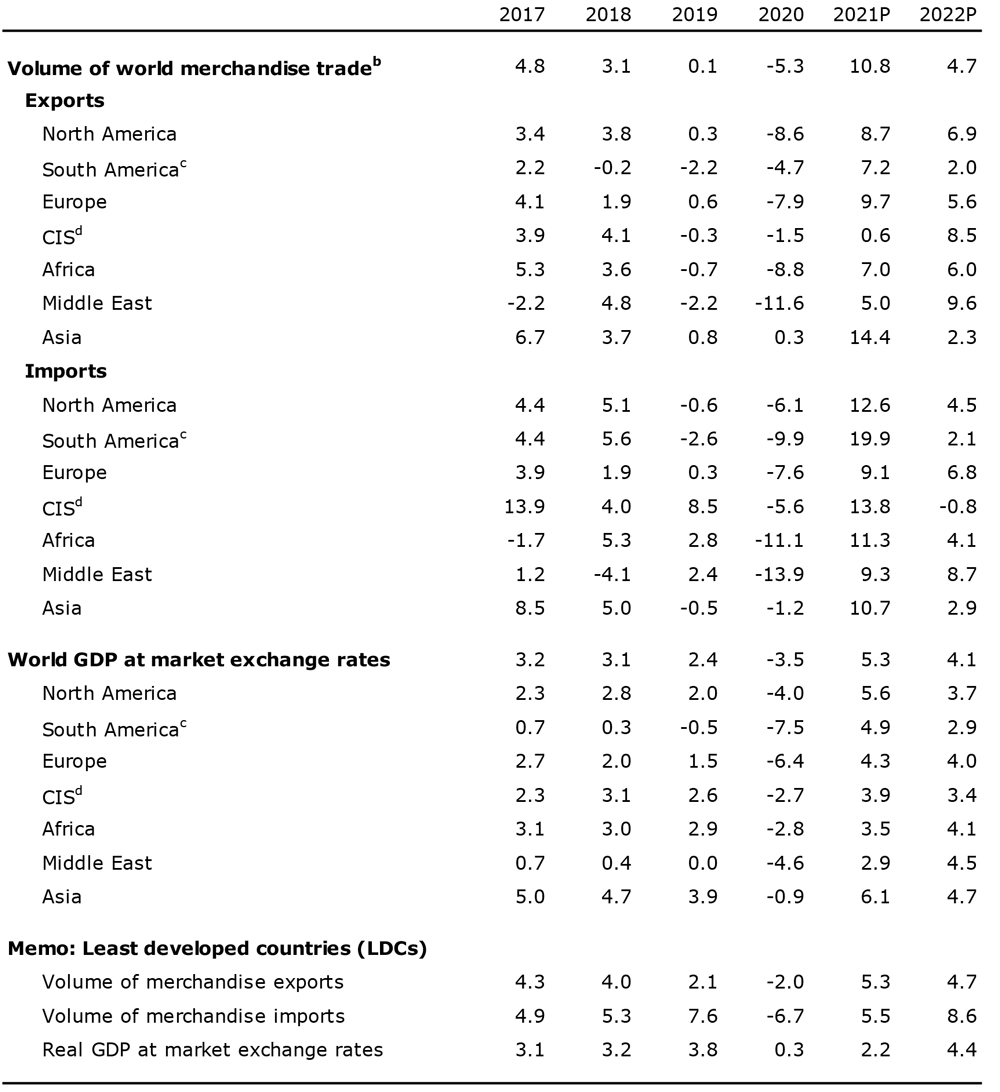

Table 1 summarizes the WTO’s annual forecasts for merchandise trade volume and real GDP at market exchange rates from 2017 through 2022. The annual figures differ slightly from the quarterly numbers for reasons of statistical methodology, but they tell a similar story of regional divergences. In addition to the five WTO regions, the table also includes estimates for Least-Developed Countries (LDCs). The numbers show that the poorest countries saw their merchandise exports decline less than the global average in 2020, while their imports declined more.

The forecast projects export volume growth in 2021 will be 8.7% in North America, 7.2% in South America, 9.7% in Europe, 0.6% in the CIS, 7.0% in Africa, 5.0% in the Middle East and 14.4% for Asia. Imports in the same year are set to grow by 12.6% in North America, 19.9% in South America, 9.1% in Europe, 13.1% in CIS, 11.3% in Africa, 9.3% in the Middle East and 10.7% in Asia. Exports and imports of LDCs will increase by an estimated 5.3% and 5.5%, respectively, in 2021.

As with the quarterly figures above, annual trade growth figures for 2021 are to a considerable extent a function of the decline suffered by each region in 2020. The pandemic’s impact on trade is better illustrated by looking at cumulative growth over the two years from 2019 to 2021. If the second half of this year turns out as expected, world merchandise trade will be up 4.9% compared to 2019. Over that period, export growth will be -0.6% in North America, 2.2% in South America, 1.0% in Europe, -1.0% in the CIS, -2.4% in Africa, -7.2% in the Middle East and 14.7% in Asia. Meanwhile, import growth between 2019 and 2021 will be 5.7% in North America, 8.1% in South America, 0.8% in Europe, 7.5% in the CIS, -1.0% in Africa, -5.9% in the Middle East and 9.4% in Asia. For LDCs, the volume of merchandise exports will increase by 3.2% between 2019 and 2021, while their imports are set to decrease by 1.6% over the same interval. This divergence continues into the projections for 2022.

Table 1: Merchandise trade volume and real GDP, 2017-2022a

Annual % change

Nominal trade developments

The WTO’s latest statistics on merchandise trade in nominal US dollar terms are released in conjunction with the trade forecast. These and other statistics can be downloaded from the WTO’s online database.

Chart 3 shows estimated year-on-year growth rates for several categories of manufactured goods trade through the