9th August

International Day of

the World’s Indigenous People

Food habits of indigenous people – 6

The Bhotia and Anwal are two native Hindu tribes co-inhabiting the Namik Valley of Uttarakhand, a state in northern India crossed by the Himalayas. The Bhotia are greater in number and are distributed over the Trans-Himalayan belt, whilst the Anwal are solely found in the hilly forested and remote area of Uttarakhand.

Traditionally, the Anwal are mobile migrating shepherds, whilst the Bhotia were primarily involved in the Indo- Tibet trading route. Currently, the two groups collaborate through an integrated agro-pastoral food system in which the Anwal continue being migrating shepherds amongst Bhotia cultivators.

Conventionally, the Bhotia and Anwal have always practised hunting and gathering of wild game and edibles. However, conservation policies have prohibited hunting activities and progressively restricted their access to forests, thus reducing their access to wild edibles species.

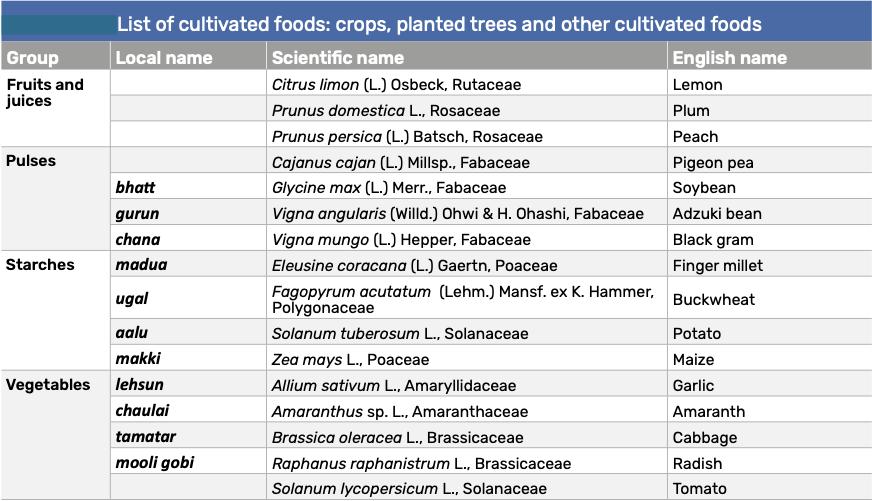

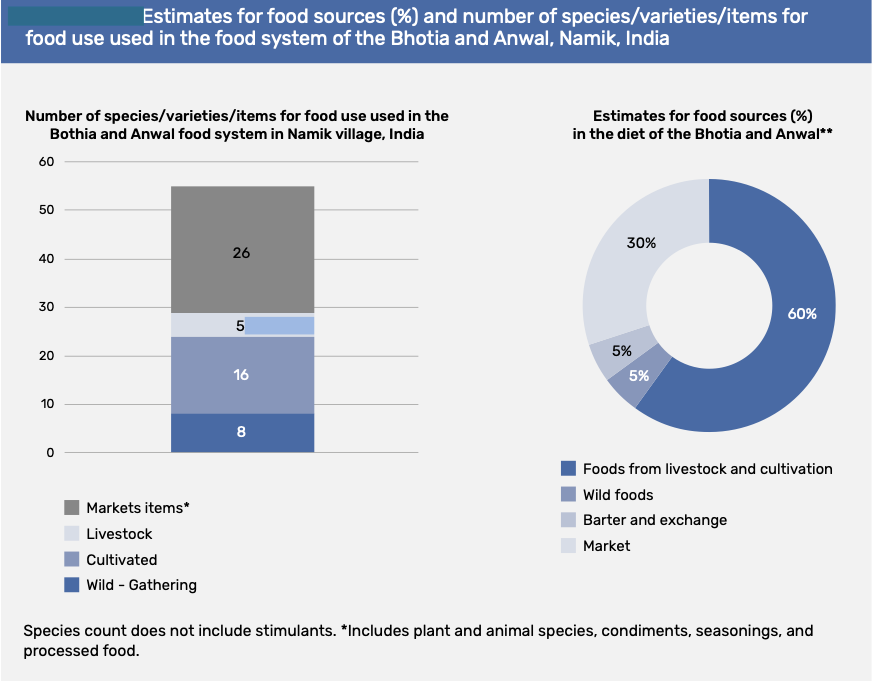

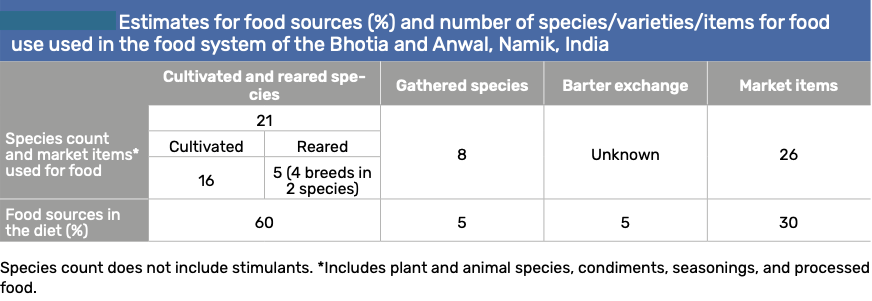

In total, the food system relies on 29 species used for food. An additional 20 species are dedicated to non-food uses for fodder, construction and materials, and medicine. Today, the market covers an estimated 30 percent of the food needs.

Pulses, in association with maize and potato, are the major staples cultivated by the Bhotia, who also keep bees, poultry, cattle and buffalo. The Anwal take care of sheep and goat herds. Whereas fishing and hunting have always remained marginal activities, the inhabitants of Namik still devote great importance to the gathering of wild plants used as foods, medicines and raw materials for craft.

Women are the main actors in the food system, as they carry most of the farming and gathering activities. The natural ecosystems provide fodder and grazing lands for livestock whose dejections serve as manure for the traditional cropping system. In this diverse system based on complementarity, barter is a relevant mode of exchange for the resilient circulation of goods.Yet the market remains necessary for enabling access to food items not generated within the system, especially rice, wheat, salt, sugar and cooking oils.

Activities are paced along five distinct seasons, including the monsoon, which heavily affects the activities during the annual cycle. Road construction, protection of wildlife and access to markets have been the major drivers of change. The abandonment of foraging in the wild has accompanied a greater demand for marketed goods and a slow dismissal of lesser-used crops, reducing the diversity of the local dietary regime. As high-altitude ecosystems are more exposed to climate change, remote villages are increasingly sensitive to more occurring natural calamities, which now bring about stress and uncertainty.

The community rears a variety of livestock, such as badri cow (an indigenous cow breed of Uttarakhand), buffalos, mules, sheep and Changthangi goats (pashmina goats introduced from Tibet). They keep these herds either in the meadows or in the forest areas near the village. Two to three community members live with these herds to look after them, and particularly men from different families take turns looking after the herds. Cows and buffaloes provide milk and milk products such as cream, which is used to prepare butter, clarified butter called ghee, buttermilk and yoghurt. The women are responsible for milking and the production of dairy products.

The community rears sheep and goats for meat and wool. The men shear the livestock and, thereafter, spin the animal hair to make thread. Women primarily weave and make jackets and carpets, whilst men knit sweaters. In contrast to cows and buffaloes, sheep and goats are taken to the meadows or the forest for free grazing. Regarding fodder, cows and buffaloes mainly feed on green leaves of oak species, ringal, and burash, which are collected from the adjoining forests. Celtis australis L., Cannabaceae, phar patti and Horse chestnut are also collected in lesser quantities. Some families have started growing napier grass around their farmland and home gardens. The community also uses chata (a mixture of flour, rice, salt and barn) as fodder to provide extra nutrients. Further, women collect dry leaves for cowshed bedding and manuring.

Beekeeping is also part of the community’s food system. Approximately 20 percent of the families have traditional log beehives made of oak or toon trees that are kept near a shade in the house. The nectar is mainly collected from wild and farm flora. Once the hive is mature and has produced honey, families extract it manually and collect it in jars and plastic bottles. However, the extraction is somewhat harmful as the manual method kills larvae in the process. The honey serves mainly as medicine to treat sore throats, coughs and colds. During religious ceremonies, households also offer honey to local deities.

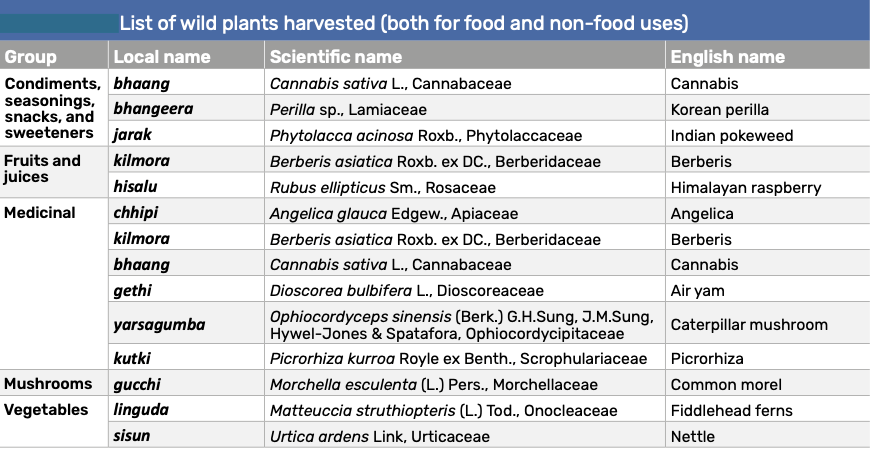

The community has in-depth knowledge of wild edible plants. The women primarily collect these plants and use them as food sources as well as for medicinal purposes for their households.

Wild edible and medicinal plants are collected from nearby forests and high-altitude meadows. They use jarak (Phytolacca acinosa, Indian pokeweed) for snacks and vegetables, and bhangeera (Perilla sp., Korean perilla) as a spice and dip to serve as chutney. Bhaang (Cannabis sativa, cannabis) is used for many purposes. The seeds are added to cuisine and chutney as a spice, whilst hemp is used to make ropes. The fluids extracted from the leaves are used to cure wounds. Sisun (Urtica ardens, nettle) can be consumed as a green vegetable, whilst the hemp is used to make ropes as well. Gethi (Dioscorea bulbifera, air yam) is eaten roasted or boiled and can relieve gastric pains. Kutki (Picrorhiza kurroa, picrorhiza) is a painkiller that can also be ingested to treat fevers. Chhipi (Angelica glauca, angelica) is consumed as an energy drink. Hisalu (Rubus ellipticus, golden Hymalayan raspberry) is eaten as fruit, as well as kilmora (Berberis asiatica, Asian barberry), which can also be used to treat asthma and coughs. Linguda (Matteuccia struthiopteris, fiddlehead ferns) is consumed as a green vegetable. After snowfall, the community harvests gucchi (Morchella esculenta, common morel), a rare mushroom in the area, for consumption. Certain orchids are used as plaster applied to bone injuries of cattle.

Traditional healers in the village have a deft understanding of the power of medicinal plants. They collect the rare and recently discovered yarsagumba (Ophiocordyceps sinensis, a caterpillar infected by fungi) and the locals sell it at a high price due to its medicinal value. Trading the fungi is illegal, but it is smuggled into China through the Nepalese border. The fungi are high in protein. China uses the plant to produce various energy drinks, and due to this utility, purchasing the plant in China is quite expensive. Several people also believe that they can produce impotency medicine from this plant. Despite the plant’s high demand, the only manufacturing done by the community is cleaning the mushroom before selling it to local traders.

(Source of the article, tables and photo: Indigenous Peoples’ food systems: Insights on sustainability and resilience from the front line of climate change (Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations)

– global bihari bureau