[the_ad_placement id=”adsense-in-feed”]

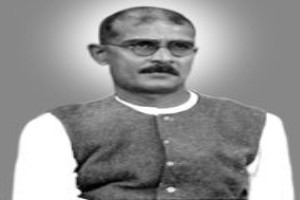

Mahadev Desai

First Person

Our educated people need to make journalism a serious and sacred profession

[the_ad_placement id=”content-placement-after-3rd-paragraph”]

By Nachiketa Desai*

By Nachiketa Desai*

Reproducing below Mahadev Desai’s speech at the journalism session of Gujarati Sahitya Parishad in 1936. The original speech was in Gujarati. Mahatma Gandhi was the president of the Parishad that year, while Mahadevbhai made this presentation on behalf of the Journalism Department of the Parishad.

When we say ‘newspaper’, we only think of a daily and I have practically no experience of running a daily except for having been the editor fifteen years ago of the newspaper, The Independent, for a limited number of days. I also know that that experience too was for a specific objective. It was a war then. The printing of the newspaper was stopped after Rs. 2,000 was demanded as a security deposit. Though a copy of my handwritten newspaper fetched as high a price as Rs. 30, I was yearning to go to jail. When I finally got the honour of going to jail after a couple of days of that crazy game of bringing out a handwritten newspaper, I did some introspection and said, “God has saved me from a doubtful situation in which it was difficult to judge if I was violating the principle of truth and non-violence. I express my gratitude to Him for saving me from this difficult predicament.” It is true that after this I have had the experience of managing weeklies under the guidance of Gandhiji and which I still continue to do. Considering the special nature of Gandhiji’s journalism, my right to stand here does not increase but, in fact, becomes limited. Gandhiji’s thoughts on journalism are not unknown and many might consider them as antiquated and anti-progressive. I believe that since you have made Gandhiji the president of the Sahitya Parishad, some of you might have thought it proper to honour his associates as well. That is why Kakasaheb (Kalelkar) and I are present here.

Also read:

To what extent is journalism literature?

However, this is not a conference of journalists but one of litterateurs who want to encourage journalists. This changes the position to some extent and makes my task easier. I have noticed that earlier conferences (of journalists) have been held independent of the Sahitya Parishad. This is the first instance of considering journalism a part of the Sahitya Parishad. This means that journalism has been considered as one of the many forms of literature. One English author has described journalism as ‘literature written in a hurry’. Many refuse to accept journalism as literature. I think it is wrong to fight over this issue because of the vague definition of literature. Let us consider Ruskin’s definition of immortal literature. Let us examine to what extent the writings in books, newspapers and weeklies fit this definition. This is Ruskin’s definition: “What I write with the consciousness that it is true, in the public interest and is beautiful is literature. The writer believes that no one else has said such a thing and that no one else can put it forth in a more beautiful way. This is his writing and is worth becoming a stone inscription in as much as whatever little he has received the vision from God. This is timeless literature.” I have used the word ‘literature’ in this quotation. Ruskin has used the words ‘timeless books’ while differentiating between ‘books’ and ‘newspapers’ and between transient and permanent literature. He has defined transient writing as that which is a readable description of an incident or of a coherent conversation between certain friends or a speech which we would like to read along with our morning cup of tea and which we must and should feel sorry if we do not read and make use of it. In no way is it eternal literature. How much newspaper writing would fit his description of eternal literature? How much writing in Indian languages and English dailies, weeklies and monthlies would qualify as eternal literature as defined by him? At the most a few quality articles would qualify as transient readable writing as defined by Ruskin. The rest of the writings do not even deserve to be mentioned as transient literature.

Yet Edison, Defoe, Hazlitt, Dickens, Edwin Arnold, Kipling, Goethe and Anatole France were journalists as well as litterateurs, or one can say they were litterateurs because they were journalists. I still remember the report in ‘Manchester Guardian’ I had read while in Agra jail in 1922 on Gandhiji’s trial in Ahmedabad. I don’t get tired of reading it again and again. I call it literature.

Back home, we cannot do without counting some of the articles by the late Manilal Nabhubhai, Navalram, Tilak Maharaj and Gandhiji as pure literature. The thoughts in these writings are read today and will be read in future. Today, Kakasaheb’s articles have been published in book form. All these articles were published earlier in newspapers and yet the value of some of them as literature does not diminish.

Double-edged sword

What should we do so that our journalism can be counted as literature? Only a few men have the authority to write immortal literature. Here I only want to discuss how we can bring our journalism into the category of what Ruskin described as transient but good reading material. To be considered good reading material, an important condition is that it should be instructive, entertaining and generally beneficial to society. Modern newspapers, like factories, are a product of the West. Like our factories are copying the factories in their initial phase, the Indian language newspapers are like the blotting paper of the western newspapers and our English dailies too are following them blindly. There is nothing objectionable if we follow the strong and good aspects of the western newspapers. Just as the use and misuse of machinery is possible, so it is with newspapers because like machinery the press is a super power. Lord Rosebery had compared newspapers with the Niagara Falls. And, without knowing about this comparison Gandhiji had independently said: “A newspaper is a super power. Just as uncontrolled flow of water submerges villages and destroys standing crops, an uncontrolled pen causes destruction. If the control comes from outside, it proves to be more poisonous than without control. Only self control can be beneficial. If this principle is right then how many newspapers in this world can survive? But who will close the useless? Who would decide who is useless? The useful and useless will continue side by side and it is up to the mankind to choose which one it wants.”

Thus a newspaper can be like a double-edged sword because it has two sides. Newspapers can be a business, a source of income and commerce and we know that they have so become. On the other hand, they can serve the people just as the municipality provides water through taps and the post offices deliver invaluable services. When they become only a source of income generation then they become destructive. When a journalist while earning his daily bread serves the people through his newspaper, he becomes an essential part of public life.

The sanctity of news

News is the life and blood of a newspaper. There is an art in the collection and dissemination of news. Whosoever perfects this art not only serves the people but serves his own self. Thus newspapers render important service by giving news. What if the news is not true but false? If they don’t do anything wrong they help the government earn good money from postage and telegrams. When some newspaperman published a rumour that Gandhiji was to pass through Bombay on the 27th, I had to write heaps of letters and telegrams! What if the news is given not as a service but to do disservice? What if they give news to provide a spark to the gunpowder when there is tension between communities? What if they give truthful or half-truth or suspicious news with a view to igniting a war at a time when peace or war is to be decided in a matter of minutes? What if the rumour of a massive general strike is given out as news when there is strife between the workers and mill owners? In such cases, a journalist ceases to serve people and becomes their enemy, one who instead of providing the elixir of truth gives poison of untruth. How many times do the newspapers ignore such a fundamental principle to boost their circulation by a few more copies? How by publishing the so-called letter said to have been written by Gandhiji to the viceroy while he was in jail, a newspaper had set off wild speculation among people. Recently another newspaper, by publishing a rumour as news about the so-called correspondence between Lord Halifax and Gandhiji, had harmed its own interest, its reputation and the interest of the country. Ever since the epidemic of communal hatred has beset us and is spreading like plague from time to time, several rag-like newspapers have come up, especially in the north, which spread poison through false news. How many people have been murdered because of such poisonous news? Recently an Urdu rag published a baseless report from its correspondent saying that a certain person met Gandhiji who, during their meeting, praised Islam, denounced the Hindu religion and recited verses from the Quran. We asked a friend to meet the editor of that Lucknow newspaper and inquire with him the purpose of publishing such a blatant lie. When the friend met him, the editor shamelessly replied, “We published the news because we received it; we are ready to publish your denial. But, if we publish the denial it would only mean that Gandhiji has no respect for Islam!” This is not the place to criticize this nor is it necessary. This only shows the limit to which our ill-fated country has declined. A journalist reflects as well as creates public opinion but in our state of slavery and in the process of the country’s development, it becomes his bounden duty to mould public opinion and strengthen it with truthful news. The blatant lie reported by that Urdu newspaper was lifted by several other Urdu newspapers following which I received dozens of letters asking me, “What is the truth about Gandhiji’s conversion to Islam?”

Commitment to truth is the prime responsibility of journalists and their newspapers than anyone else’s. Baldwin had quoted the words of England’s venerated journalist C P Scott before a gathering of journalists which should be put up on a large sign board in every office of newspapers:

“Fundamentally it implies honesty, cleanness, courage, fairness, a sense of duty to the reader and the community. A newspaper is of necessity something of a monopoly, and its first duty is to shun the temptations of monopoly. Its primary office is the gathering of news. At the peril of its soul it must see that the supply is not tainted. Neither in what it gives, nor in what it does not give, nor in the mode of presentation must the unclouded face of truth suffer wrong. Comment is free, but facts are sacred. The voice of opponents no less than that of friends has a right to be heard. Comment also is justly subject to a self-imposed restraint. It is well to be frank; it is even better to be fair.”

Truthfulness is the prime duty

Some newspapers think it fashionable to exaggerate or use ornamental language. To the American newspaper a style bereft of such ornamental language might be thought as uncivilized. One American reporter asked me: “Does Gandhiji like cats?” I said: “He also likes dogs, cows and also you, why just cats?” He laughed and said: “I want to give a word sketch of the atmosphere around Gandhiji. It would become colourful if I can place a cat somewhere in it.” He made it colourful by describing a cat drinking milk sitting next to Gandhiji. The journalist thought it was only possible to describe Gandhiji as a humble saint by citing an imaginary scene. So he wrote: “When the Prince of Wales came here Gandhiji prostrated before him.” Scolding him, Gandhiji said: “This lie of yours puts even your imagination to shame. I would prostrate before a scavenger and kiss the dust of his feet because I have participated in the sin of making him work in the dust. But, I would never prostrate before even the Emperor, leave alone the Prince of Wales because he is the representative of an oppressive regime.” Why just talk about foreign journalists, our own journalists have now surpassed them.

We feel proud in publishing useless and frivolous news reports, not to speak of false news. Should we publish all the news that is received? It would be useful to know the policy of the famous American newspaper, Christian Science Monitor, in this regard. I had met its London correspondent in London. Whenever misleading news about India would appear in the London newspapers, he would come to me to verify such news and only then send his reports to America. The newspaper is well-known for its commitment to public interest.

The honour of individual members of society rests with newspapers and the law of civilization is more applicable to newspapers than individuals. But how many newspapers follow this rule of modesty? Some newspapers in Punjab are said to be surviving on blackmailing people by threatening to publish slanderous news about them. There is also the possibility of indulging in uncivilized behaviour and insulting someone by revealing truth. When news is received about an individual’s personal life, one should not accept it without proof and without verifying minutely if the proof is true. And, before deciding to publish the report one should think if doing so would be in the interest of the society or not. Is it a difficult policy to follow?

Filth in newspapers

We have not risen above our petty squabbles and several weeklies – especially those in Marathi – have made mudslinging and contemptuous writing their business. Assured that Congressmen would not drag them to court or if they do so, there is nothing to lose, they are least ashamed of defaming eminent leaders and their institutions. They take pride in twisting facts and cite obscene but popular metaphors from Marathi folklore. I shall place here only a recent example which a Marathi reader has sent me of how these weeklies depict a distorted version of a straightforward case to convey the exactly opposite meaning. I had written in ‘Harijan’, “Segaon is five-and-a-half miles from Wardha hence everyone gets a compulsory exercise of walking 11 miles.” The weekly has distorted this information to say, “While Gandhi happily sits in the village, he shamelessly makes others walk.”

Why should we find fault with only Marathi newspapers? There are so many in Gujarat that can beat them in the game. The only difference is that while the Marathis have brains, our newspapers have nothing other than mischievous mind. It is disgusting to give instances from them. To put them on paper is like blackening the paper. It would be sufficient to show a few samples from their deviously mischievous reports: “Gandhiji had described temples as brothels, now his own ashram has turned into one. Boys and girls are indulging in acts of pleasure because of co-education. Gandhiji was compelled to fast. The ashram inmates have become cowards. It is like handing over the Satyagraha Ashram to the government….Finally today only the chamars are staying and they are tanning hide and making shoes in the Ashram.” “Gandhiji has much malice against the Hindu religion. It is said that mainly Muslims had supported his struggle in Africa and very few intellectual Hindus had supported him and so he is taking revenge on Hindus. Only God knows if this is true or false but it is a fact that even the Muslims have not tried the kind of efforts that Gandhiji has made to destroy the Hindu religion.”

The weekly ‘Manchester Guardian’ is worth copying on several counts. It contains a lot of well-chosen news reports, views of present leaders on social, political and economic issues, a balanced description of the world affairs, reviews of selected books and a few articles on pure literature. It is true that at times it carries thoughtless criticism and misleading news reports but it also has the honesty to carry out the necessary corrections as soon as these are brought to its notice.

I would like to conclude my views on news with a quotation from Ruskin: “If a newspaper, daily or weekly, is satisfied by giving selected truthful news and views, after verifying their truthfulness, and decides to give from out of all that is received by it only that which is worth knowing and enriching the soul in pure language, I cannot then say if it will make profit or not but it will definitely profit the reader.”

But are the newspapers bothered about the readers’ profit?

News from broad perspective

Let us now leave the topic of news and move ahead, though reports of speeches and interviews too broadly fall under the category of news. In this field, we can still be considered to be in infancy. There is only one English newspaper which can be described as performing its role satisfactorily in this field. This is the Madras-based The Hindu. It has correspondents in every mofussil town who know shorthand. The Amrita Bazar Patrika of Bengal too is trying to come up to the level of The Hindu. All other newspapers fail to meet expectations in this regard. Our English and Gujarati newspapers do not have the capability to report the gist of an interview or speech without the help of notes. The famous journalist Blovitz had gone to Versailles with Delane, the editor of The Times, in 1872. Both heard the speech of French Premier Thieres and returned. While seeing off Blovitz, Delane said, “Such speeches should be reported verbatim. It would have been good if tomorrow’s paper could carry this. But how can this be possible?” Delane returned to London. From the railway station, Blovitz went straight to the telegraph office, procured paper and started writing. He would close his eyes, recall the image of the meeting and Thieres’ facial expression and words. In a while the entire speech was ready and reached London by telegram. The next day, Delane was amazed to find Thieres’ full speech of Versailles in two and a half columns of The Times. I am not aware of any Blovitz amongst us. I hope I am wrong. In today’s time, it is not impossible to get such reporters. The real need is for the study of various subjects and concentration.

Here too the moot issue is that of truthfulness and sense of justice. Let me give a recent example. A meeting was organized in London to start “Activities of a new era in India”. The Archbishop of Canterbury presided over the meeting. Look at the two reports on the meeting and observe how both create entirely different impressions. Here is the Reuter’s report:

“A meeting to begin ‘Activities of a new era in India’ was held in London which was presided over by the Archbishop of Canterbury. In his presidential address, he heartily acclaimed Mr. Gandhi’s efforts for raising the standard of living of India’s village folks. The meeting was organized by several Christian missionary associations working in India and among the speakers was Lucknow’s Bishop Picket.

“The Archbishop of Canterbury especially emphasized that he would never give his consent to the misuse of activities for the uplift of the untouchables for political gains.”

Now see the same day’s report by the London correspondent of The Hindu:

“There was a big meeting held at the Central Hall of Westminster last night. At the meeting, reports of various Christian missionary associations’ programmes aimed at converting untouchables to Christianity were presented which aroused people’s interest in the future of India’s untouchables.

“The Archbishop of Canterbury, while praising highly Mr Gandhi’s work, made it amply clear that notwithstanding the utterance by ignorant political critics about Mr. Gandhi, neither he nor Christian missionaries have any doubt about the moral influence he has wielded and continues to wield. The Archbishop said everyone, especially the leaders of public opinion in India, should be told in clear terms that no association working among the untouchable would misuse any political movement for the propagation of Christianity and that they are not interested in taking part in any move by political parties aimed at auctioning people’s souls. He also clarified that there would not be any mass conversion if crowds of people approach them for reasons of social or economic compulsions and that only those would be accepted into the fold of Christianity who have properly understood the Christian religion and its responsibilities.”

Now which report is true, Reuter’s or The Hindu’s? By deleting the words ‘for the propagation of Christianity’, the first has given a totally different meaning to the complete speech, praising Gandhiji’s work on village reconstruction instead of his work for the abolition of untouchability.

Thus many a time, summarizing a speech can grossly distort its meaning. Gandhiji would have lost his life because of the summaries of his Indian articles published in South Africa. When the full text of the same articles was published there, the residents of Africa repented for having attacked him.

If we are weak in this aspect of reporting, we are weaker in giving credible descriptions of a situation based on its in-depth study. I must say that some of our monthly magazines have begun covering up this deficiency. The monthly ‘Prasthan’ and the new monthly ‘Sarvodaya’ started by labour union workers do carry well-researched articles on various economic issues. However, there is a famine of such material in dailies. In this regard, we need to learn a lot from newspapers of Maharashtra. One would find many well-researched articles on different subjects in the files of the daily ‘Kesari’ of the time of Tilak Maharaj or Kelkar’s. Never was the need for such well-researched articles so urgent as today. The scope of our politics and economics has become wider. We have begun to realize in the last 15 years that the real India is in villages, among farmers and among the working class. Yet, our newspapers are published from cities and whose reporters follow some leaders on their visits to villages and report their speeches. There are very few journalists who study the problems of villages, economic conditions of farmers and their hardship by living amidst them. We find such journalists fewer in number among the various journalist associations. I have heard from Tilak Maharaj that he used to make it compulsory for journalists working under him to choose a topic related to economic affairs, study it for five years and then take his test by making him write on it. I have already referred to C P Scott about who I am going to speak in some detail. It was said about his newspaper, Manchester Guardian, that it was a university in which bright graduates from Oxford and Cambridge used to take up jobs as journalists but their real education began under Mr. Scott.

We should request specialist writers to contribute analytical articles on some important events. In a shocking case, which became popular as Khord-Govindpur case tried by the Calcutta High Court, the Amrita Bazar Patrika criticized the court’s judgement, quoting the law, which was so hard-hitting that the judge was annoyed but could not take any action against the newspaper. It became a matter of widespread discussion in the whole of Bengal. A few poor tribal villagers of Bardoli taluka suffered greatly at the hands of the government. They were first jailed for not having paid fine and even after their release from jail their household goods were attached. The High Court gave them justice after a long trial and passed strict stricture against the government. Yet, the case was not discussed as widely as it should have been. There are innumerable such cases of injustice in our province.

Promoting good taste

Not a single newspaper gives importance to features that seek to promote good taste, encourage aesthetics and delight the mind. While we publish obscene photographs, why can’t we carry cartoons on the current political and social situation? The art of cartooning has developed well in the West. Shankar’s cartoons in The Hindustan Times are of excellent quality. If newspapers start promoting them, there would be plenty of cartoonists. There is also a need to develop the art of writing short pieces which excite the mind of readers and nourishes their sense of humour. Joseph, the then editor of The Hindustan Times, was superb in this art. I am reminded of one paragraph by this writer which makes a mockery of the sanctions announced against Italy for atrocities against the people of Abyssinia which, though much talked about, no one had the intention of implementing: “Now that sanctions have been announced, just see how strictly they are going to be implemented! There will be boycott of macaroni and spaghetti at dinners in New Delhi. No one will touch Italian wine and since brave France is going to be the first to implement the sanctions everyone will demand French Champagne. Newspaper employees should get long leave because everything is written in roman type or in Italics. And, because most of the words in English are derived from Latin, the language of the aggressors, Italians, it should be boycotted, boycotted, boycotted!”

Gaganvihari Mehta is known for writing long satirical articles with a social message. His language full of sarcasm is quite enchanting. I can’t give here the full text of his articles. But his satire on our cowardice, our tendency to blame our own defects of lack of sacrifice and industry on others would make us introspect and have fun. I will give here only some glimpses from this long article:

“Every morning while doing the great patriotic act of reading a newspaper, innumerable people feel that if only an adequate number of people had courted jail, faced blows of the cane and taken the pledge of swadeshi we would have got at least some element of independence if not complete independence. Many patriots have assured me that if only one lakh men were ready to lay their life for the mother land, India would have definitely won independence….

“Why is it that though leaders of both Hindu and Muslim communities are unanimous about the need for unity, unity is not achieved? Who creates all these misunderstandings and quarrels? Surely, members of some other community. This is why the leaders constantly appeal for unity to other people and other leaders……

In the same way, but of a different type and flair, are the satires by ‘Swairvihari’ Ramnarayan Pathak. Look at his column on our tendency of collecting garbage:

“People unnecessarily complain against garbage. What can garbage do but increase? Bombay’s civic officials install large cans for the collection of garbage. Our village too has created a demarcated place for collecting waste. But the garbage is bound to spill over. Ocean will not cross its boundary, but garbage will. Those who complain against it have no sense. They will not complain if they understand the reason. Garbage is where waste is collected. Now, clean people like us cannot go near such a dirty place. So, we throw the waste from a distance. In the process, some of it would fall near the person who throws it. When a player throws the tennis ball it does not always pitch in the intended place of its fall. Now, garbage is not a single tennis ball. It contains many elements smaller and bigger than the ball. The garbage collection drum is not of the size of a tennis court. Therefore, while throwing the garbage, a part of it is bound to spill up to the person throwing it. Thus, the boundary of the garbage expands. When the next person comes to throw the garbage, he takes up position from the new ‘boundary’ and aims at the drum, spilling some of it up to where he is standing. Now, what can the poor people do if in such a way the extent of garbage keeps on expanding?”

Why should such interesting writing remain confined to monthlies and the readers of dailies and weeklies denied the pleasure? However, the idea of providing interesting reading material to their readers seems not to have appealed to dailies and weeklies.

The editor

We now come to the editor and the journalists who create a wholesome lively newspaper by collecting all these elements. Much depends on the objective of this creation. 1. Some editors believe in only reflecting the public opinion without going into its merits or demerits. 2. Some editors, after sensing public opinion, believe in influencing it and if occasion demands, carry out powerful campaigns even at the risk of going against public opinion and inviting the wrath of the people. 3. Some editors perform the role of public educators who bring about revolutionary changes in the society. Editors of the first category are found aplenty. There are only a handful of the second and third categories.

Call it God’s grace that we have editors like C Y Chintamani, Ramanand Chatterjee, Motilal Ghosh, Natrajan and Kalinath Roy. People like Gandhiji and Tilak Maharaj, who can overcome the toughest of challenging situations and obstacles, are rare. There are other journalists who have made their newspapers financially successful, who have adopted a policy of not to provoke either the government or the people and chosen to flow with the tide. We have such successful newspapers not only in English but also in Gujarati. I do not want to discuss about such ‘successful’ newspapers. My eyes are trained only on the newspaper committed to educating the people and serving the country. Therefore I will only talk in detail about the second and third types of editors.

Famous foreign journalists

It is better to talk about foreign journalists from who we need to learn as much as possible because journalism is not an indigenous but a foreign art.

Words fail me when I think about Lloyd Garrison. No satyagrahi can ever forget this brave crusader who fought against abject and cruel slavery without bothering about its dangerous consequences. Once, he had unwittingly said slavery should end in phases. But he soon realized his mistake and did not hesitate in accepting it publicly and felt it his bounden duty to express remorse. His utterances on that occasion have become famous in history: “In Park-street Church, on the Fourth of July, 1829, in an address on slavery, I unreflectingly assented to the popular but pernicious doctrine of gradual abolition. I seize this opportunity to make a full and unequivocal recantation, and thus publicly to ask pardon of my God, of my country, and of my brethren the poor slaves, for having uttered a sentiment so full of timidity, injustice and absurdity. I am aware, that many object to the severity of my language; but is there no cause for severity? I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject, I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! no! Tell a man whose house is on fire, to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hand of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen; — but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest — I will not equivocate — I will not excuse — I will not retreat a single inch — AND I WILL BE HEARD.”

Every journalist has many a thing to learn from the life and work of these two eminent journalists of England. The biography of C P Scott in particular is the biography of a saint reading which would make one pious and elevated.

When he retired after 57 years of editorship even the Emperor thanked him for his unparalleled services. The Prime Minister had said that as a result of Scott’s services the world had become more liveable and General Smutts had said that his life and work had strengthened the foundation of civilized and moral life of countless people.

The mere thought of such a man is blissful. He has made journalism an honourable profession and his life and work will continue to inspire future journalists. The conditions of his country would surely have made his work a bit easy. Will ever the Emperor thank Gandhiji and Tilak Maharaj? They can only be the welcome guests in the Emperor’s prison. The pursuit of journalism using ethical means, commitment to truth and with fearlessness is as difficult as pursuing a career in law as an advocate honestly. Scott had perfected this art. The ideals of Gandhiji, Tilak Maharaj or Garrison might be impossible or difficult to follow, but the ideals of Scott are comparatively easier to emulate.

A serious and sacred profession

Our educated people need to make journalism a serious and sacred profession. Today, newspapers and journals are sprouting like mushrooms and vanishing like bubbles. Our newspapers can attain the desired reputation if only a few of our competent writers start contributing their mite to this noble profession. Those who are in the profession have made it a means to earn money and those who have talent are pursuing some other profession. If talented and progressive writers and poets start writing for newspapers, it would enrich the content with variety and beauty. The present condition would vastly improve if the doyens of Gujarati literature start encouraging and training budding writers. I don’t have any idea what the Gujarati Sahitya Parishad can do for this. We all need to put our thoughts to this urgent need. The task of removing the filth of advertisement and other such unwarranted features is daunting as many newspapers are trapped in this murky business. It is like fighting a fire spread across the ocean. Does the Sahitya Parishad have the power to fight such a fire?

*Nachiketa Desai is a senior journalist and grandson of eminent freedom fighter and Mahatma Gandhi’s personal secretary Mahadev Desai.

[the_ad_placement id=”sidebar-feed”]