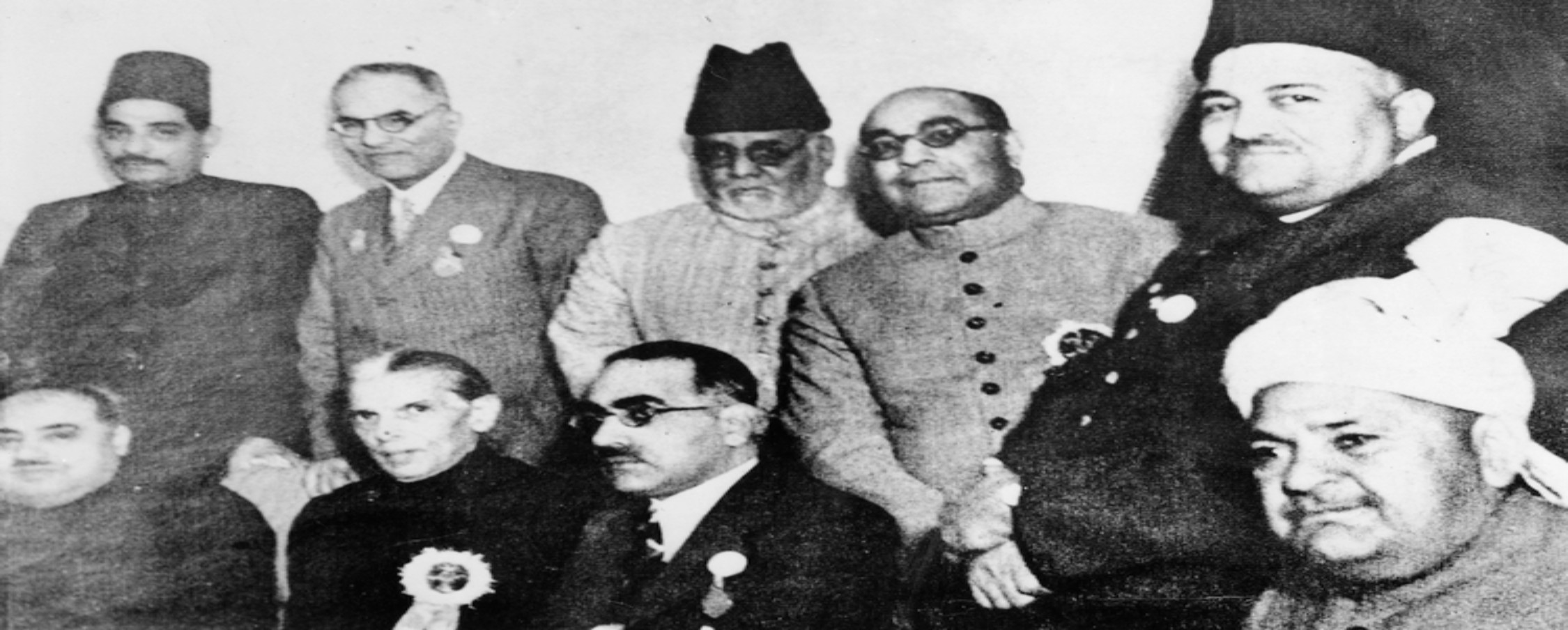

Jinnah (front, left) with the Working Committee of the Muslim League after a meeting in Lucknow, October 1937

(This file has been provided by the British Library from its digital collections.Catalogue entry: Photo 429/(4), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25625979)

[the_ad_placement id=”adsense-in-feed”]

First Person

Jinnah’s main charge against the Congress was that it was a Hindu organisation

By Nachiketa Desai*

By Nachiketa Desai*

(From my father Narayan Desai’s book on the Partition and Gandhi ji. Translated from Gujarati to English by Nachiketa Desai)

[the_ad_placement id=”content-placement-after-3rd-paragraph”]

Muslim League’s contribution to the country’s partition was no less. Many believe that partition happened only because of Muslim League. Some also believe that Mohammed Ali Jinnah was primarily responsible for leading Muslim League towards partition.

There is some truth in both these beliefs, but not the whole truth. It is true that League’s contribution to partition was significant. But we can’t say that it was solely responsible. It is also true that Jinnah was successful in leading the League till the end. But there were also other elements supporting it.

All India Muslim League was formed in Dhaka in 1906. As we have already mentioned earlier, at the Coconada Congress session, Maulana Mohammed Ali had described it as the result of Britishers’ desire. It was said that when the British rulers realized that the demand for self-rule raised by the Congress within 21 years of its formation was gaining momentum they inspired certain Muslim leaders to come together as a counter force.

The first decade of Muslim League was marked by the leadership of some prominent rich people. That was when some Nawabs, some big landlords and a few rich Muslims used to meet once a year and pass resolutions expressing their loyalty to the British Raj and to put forward some demands of the Muslims. Nothing more than that. Yet, the British government gave the Muslims a separate electorate status. In the later part of that decade a certain amount of political awareness had come among the educated class of Muslims. For several years, the annual conferences of both Congress and the Muslim League were held in one town and mutually convenient dates so that leaders of both the parties were able to address both the conventions.

At the Lucknow Congress session in 1916 Lokmanya Tilak along with some others and on the other side Mohammed Ali Jinnah and others signed a memorandum of understanding in support of the demand for giving some special rights in the Indian constitution. At the time, the constitution of the Congress allowed members to join more than one political organizations. Therefore, leaders like Jinnah (tenure 1947-48) were members of both the Congress and the League while leaders like Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya enjoyed membership of both Congress and the Hindu Mahasabha. After the Lucknow session of the Congress, the cracks between Congress and the League became more visible.

By this time, the influence of Congress had become visible in most cities and towns of the country. The educated class looked upon it as the only party working for the country’s independence. The influence of Muslim League was restricted to its leadership which comprised mainly of Nawabs, landlords and a handful of rich Muslims. There were a few exceptions like Jinnah. His nationalism was undisputable. Gokhale had described him as the apostle of Hindu-Muslim unity. An anecdote about him is well-known. He once asked a Muslim youth, “Who are you first, a Muslim or an Indian?” When the youth tried to say, “I am a Muslim first”, Jinnah cut him short saying, “No, you are an Indian first and a Muslim next.” Barring exceptions like Jinnah, the leadership of League was confined only to the princely and feudal class. Though the leadership of the Congress too was confined to the educated intellectual class, but its influence was far wider than that of the feudal Muslim League.

It can be said that India’s leadership started paying attention to the Hindu-Muslim question after the 1916 Lucknow Congress session. However, their focus was not concerning the vast population of Muslims. It was confined to the issue of Muslim representation at the Centre and in states. But the Muslim leadership woke up after the 1937 elections. The election results were an eye-opener particularly for the Muslim League. In the North-West and North-East states, having a Muslim majority population, the Muslim League fared very poorly. However, in states like United Provinces, Bihar and Bombay, where Muslims were in minority, the Muslim League won a good number of seats. However, there were less number of Muslim seats in these states proportionate to the total population. In Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan and the Northwest Frontier province, where the Muslim population was high, the Muslim League did not perform well. Muslim League leadership described the 1937 election results as due to ‘lack of unity among Muslims’.

Since then, Muslim League, under the competent leadership of Jinnah, adopted the policy of strengthening and widening the organization in provinces where Muslims were in minority and wooing leaders in the Muslim majority provinces. In the eight provinces (United Provinces, Bombay, Madras, Bihar, Central Provinces and Berar, Orissa, Assam and Northwestern Frontier Province) where the Congress had got majority seats, the Congress got busy in managing the administration. It neither paid much attention to other states nor attempted to garner the support of Muslims. Two features of Jinnah’s strategy were obvious: Muslim League started spewing venom against the Congress-ruled states based on exaggerated accounts of ‘injustice’ and ‘atrocities’ on Muslims. In states where non-Congress Muslim ministries were in power, Jinnah’s general stand was, “We will support your demands in the state and in turn you support us at the centre.” Jinnah was more interested in central politics. He was less interested in greater autonomy for states. He had twin ambitions: To have effective presence of the League at the centre and to become supreme leader of Muslims of the entire country. For this he was willing to compromise with the leaders of Punjab, Sindh and Bengal. The leaders of these provinces needed the backing of a national leader with whose support they can get their regional demands fulfilled. That is why after the elections of 1937, Bengal’s leader Suhrawardy and Punjab’s Iqbal requested Jinnah to hold the most important session of the League in their respective province. It was not that both had special affection for him but both considered Jinnah as the only leader who could do something at the centre.

League’s 25th session, held in Lucknow from October 13 to 18, 1937 was perhaps the most important one in its entire history. The feeling of frustration on account of the drubbing in the 1937 elections coupled with the desire to show the real strength of Muslims before the Britishers and Hindus by raising a unified cry found expression in frenzy. Describing the session, Punjab chief minister Sikander Hyatkhan said, “There many speakers outdid even Jinnah in their fiery speeches and had Congress leaders been present there people would have sent them to the gallows caring two hoots for the law.” After this session of the League, Punjab’s Sikander Hyatkhan, Bengal’s Fazlul Haq and Assam’s chief minister formally joined the Muslim League. This was Jinnah’s major achievement. He got a good opportunity to enter Muslim-majority states.

On reading reports of the fiery speeches made by leaders after leaders at the Lucknow session, Gandhiji remarked all this seems like declaration of war. In defence, Jinnah told newspapermen that the war was for self-defence.

After the Lucknow session, Jinnah visited many cities and towns of Bihar and Bengal. His speeches became fiercer. At a public meeting in Gaya, for the first time Jinnah appealed in the name of Islam. Till then, League hardly had any direct contact with the common Muslims. In fact, it was only the Congress which had constructive programmes that provided employment to the poor Muslim artisans.

The thought that Muslims had lost the elections only at the hands of Muslims was instrumental in bringing together many of their leaders while the appeal in the name of Islam made their talk more acceptable among the common Muslims. After the Lucknow session, the League workers embarked on a systematic campaign in their respective areas. About the nature of speeches of leaders like Fazlul Haq, even the leaders like Sikander Hyatkhan admitted that these were so fanatical that it was difficult to predict when these would cross the limits of law.

The League held thousands of public meetings in the next one year. It set up 174 branches throughout the country of which 90 were in United Provinces, 40 in Punjab and the remaining in the rest of the states. During the same period, there were communal riots in United Provinces, Bihar, Central Provinces and Berar and Bombay. In the by-elections held that year in United Provinces, CP and Berar and Bihar, League emerged the winner.

In the 1937 elections, the Congress had become victorious in all the states where the Muslims were in a minority. According to some observers, the policy adopted at the time by the Congress in forming the ministries resulted in the first major crack that ultimately caused the partition of the country.

The elections in the United Provinces and the steps taken by the Congress thereafter are an obvious example. Before the elections, neither the Congress nor the League had any idea of the number of seats each party would win. So though they had not entered into a written agreement, in practice both contested the elections with a tacit understanding. It was the claim of the Congress that it represented the entire country while the League claimed it represented the interest of all the Muslims. However, both wanted freedom from the Britishers. Generally, rich Muslims dominated in the League while the influence of the Congress was not limited to any particular class. According the tacit understanding, both the parties would support each other in constituencies where only one of them put up their candidate. However, in constituencies where both parties would put up candidates there would be campaign against one another. There was mutual understanding between the two parties till the elections got over. Though there was no written agreement, both expected that in case both together managed to garner a majority they would share power. It so happened that the Congress got more seats than its expectations and commanded a clear majority on its own strength. At the time of formation of the ministry, the League expected that some of its victorious candidates would be accommodated in the new ministry. However, having won a clear majority the Congress did not need any outside support to form the government. So, it decided to constitute the ministry with its own elected representatives. The president of the Muslim League of United Provinces Khalifuzzama was in the Congress just a little before the elections. His relationship with the Congress was also very cordial. However, legally Congress did not require support from any outside party. The League hoped that it would be able to convince the Congress to make some kind of adjustment. As it is the Congress policy was to include at least one Muslim member in its ministry. It had entrusted the responsibility of electioneering in United Provinces and Bihar to (Maulana) Abul Kalam Azad (1888-1958). Khalifuzzama had also held discussions with him. But Jawaharlal (Nehru)(1889-1964), who was negotiating on behalf of the Congress, was very obstinate. His stand was legally correct. But the frenzy of victory defeated the wisdom in reaching a compromise. After much haggling, Jawaharlal (tenure 1947-1964) finally agreed to induct one member of the League into the ministry while Khalifuzzama wanted two. It appears that Maulana Azad (tenure 1947-1958) was ready for such a compromise. Khalifuzzama had gone to the extent of having given an assurance that since the League was not very powerful in the United Provinces one can convince it to merge itself with the Congress after a few months. The question had narrowed down to the issue of accommodating two or one League member into the ministry. But in the United Provinces, the Congress did not agree to give up its stubborn stand. The talks broke down. Maulana himself opined that the Congress missed one opportunity of preventing the split. According to Maulana if two members of the League would have been accommodated in a cabinet of nine, the League would have agreed to accept wholeheartedly the programme of the Congress and cooperated in its execution. But, Jawaharlal insisted to include only one member, not two, in the cabinet and thus the talks failed. In both United Province and Bombay Province, the League had won quite a sizeable number of seats reserved for the Muslims. In Mumbai, Sardar Patel (1875-1950) insisted that all the ministers must sign on the pledge of loyalty to the Congress.

As it is the League had got less number of seats in the whole of the country. It had got somewhat more seats in provinces where the Muslims were in minority and where the Congress had got either an absolute majority or was the largest single party. The League’s calculation that it would get some share of the power if it stayed with the Congress failed completely in all the states. Congress did not pay attention to the League’s demands as it got engrossed in ensuring the smooth running of the ministry, efficient implementation of its programmes, tackling the problems of the administration as it was the party’s first time experience of running the government, and in resolving disputes and bickering amongst its own party men. On the other hand, a feeling gained ground among the League and particularly in the mind of its leader Jinnah that if this is how things are going to be, Muslims would never be able to come to power in this country where they are in a minority. Before the British Raj, there was Muslim rule in India. This also gave rise to another thought that Muslims can never come back to power through democratic means as also the thought that democracy does not suit this country.

The membership of Muslim League increased leaps and bounds in India between 1937 and 1946. How could Muslim League, which had virtually no following in Muslim-majority states and had presence in only one or two states where Muslims were in a minority, claim to be the only representative organisation of all the Muslims of the country within a span of ten years? To find the answer, let us focus only on the main points without going into the minute details of the history.

In every country and in every era the psychology of the minority community is to establish its own separate identity. It is their natural tendency to protect, promote and glorify their identity. They take pride in their entity. They constantly try to prove their unity. Many Muslim leaders had held disunity in the community as responsible for Muslim League’s defeat in the 1937 elections. Though they themselves would not be remembering the fact that Muslims ruled over many parts of the country including in Delhi and Agra before the establishment of the British Raj, they harped on this history time and again before the common Muslim people.

After the formation of the Congress ministry in as many as eight states, not a single member of the Muslim League found place in them. This gave rise to the fear among their leaders that the minority community would never ever see power. This fear started reaching the common Muslims through the slogan of ‘Islam is in danger’. Whenever fear is nurtured, it leads to cowardice and cowardice is the mother of cruelty.

The phenomenon of communal riots which appeared after the arrival of the Britishers in India started recurring in the Congress-ruled states. For the Congress ministry this became troublesome and for the League a powerful reason to blame the Congress.

At this stage, Muslim League found in Mohammed Ali Jinnah an unrivaled leader. Thinking he would not succeed in politics in India, Jinnah had migrated to England and had a thriving legal practice to support a comfortable life there. An ambitious young man Liakat Ali Khan (1895-1951) succeeding in persuading Jinnah to return to India by convincing him that if not of the whole of India, he had all the qualities to lead India’s Muslims and that the top leadership of the community were eagerly waiting to welcome him there. Immediately on his return to India, the All India Muslim League made him life-long president of the party and thus assuring him that there would not be any challenge to his leadership from within the party.

A man with sharp brain and gift of the gab, barrister Jinnah had all the qualities of a leader who could sustain a long-lasting politics of opposition. He was a master strategist with a long-term vision, who never let others know what was in his mind, knew how to extricate himself adroitly from a tricky argumentative tangle, maintained a distance from the common man and yet understood his mindset, a self-possessed, proud and ambitious leader. In his personal life he fulfilled all his obligations towards his wife and daughter and yet lived a somewhat secluded life. Though he hardly ever followed the rules of an orthodox Muslim, he espoused their cause in politics. He would keep his intentions so secret that many a times people would doubt if he himself was clear about them. For example even after his death learned researchers are unable to resolve the controversy if Jinnah really wanted the creation of Pakistan till the end or presented its case as the demand of the opposite camp so as to have his maximum say in India’s central government. However, we can say for sure that he was successful to a great extent at every stage of his life by changing his tactics with the changing conditions.

After its failure to get a place in the Congress ministries in 1937, the League openly declared war against the Congress. Their main issues for this war were injustice and atrocities by the Congress.

Jinnah’s main charge against the Congress was that it was a Hindu organisation that nationalism was its ruse to establish a Hindu nation. The Hindu Mahasabha is better than the Congress because at least it says what it wants. Jinnah himself had begun his public life as a strong nationalist and had devoted most of his attention to the national affairs than the issues of the states between 1937 and 1946. However, by that time he had begun to think more about the interests of the Muslims than that of the whole country. Just to prove that the Congress wanted to establish a Hindu nation, he and his other colleagues in the League would make wild allegations without providing supportive evidence.

One of the League’s charge was that the Congress ended all its meetings with the singing of the song ‘Vande Mataram’. This song of Bankimchandra had first become popular in Bengal during the mass movement against the partition of Bengal and then throughout the country. Only the first stanza of this long song used to be sung. The controversy arose because it was pointed out that Muslims cannot pay obeisance to anyone else other than Allah. In the song, the country is referred to as ‘Mother India’ and is worshipped as the mother. This offends the sensitivity of Muslims. At the time when this song had become popular, thousands of Hindus and Muslims fought against the partition of Bengal, shoulder-to-shoulder and as a war cry used to sing this very song. Apparently, this mischievous thought was the brainchild of a British officer who planted it in the minds of some Muslims and soon the thought spread far and wide. Jinnah himself was not a fool who would not understand this devious game of the Britisher. However, at the time his brain worked like a clever lawyer who not only grabbed any argument that can be used against the opponent but would also further it.

One of the League’s charge was that the Congress ended all its meetings with the singing of the song ‘Vande Mataram’. This song of Bankimchandra had first become popular in Bengal during the mass movement against the partition of Bengal and then throughout the country. Only the first stanza of this long song used to be sung. The controversy arose because it was pointed out that Muslims cannot pay obeisance to anyone else other than Allah. In the song, the country is referred to as ‘Mother India’ and is worshipped as the mother. This offends the sensitivity of Muslims. At the time when this song had become popular, thousands of Hindus and Muslims fought against the partition of Bengal, shoulder-to-shoulder and as a war cry used to sing this very song. Apparently, this mischievous thought was the brainchild of a British officer who planted it in the minds of some Muslims and soon the thought spread far and wide. Jinnah himself was not a fool who would not understand this devious game of the Britisher. However, at the time his brain worked like a clever lawyer who not only grabbed any argument that can be used against the opponent but would also further it.

Among the alleged atrocities of the Congress included refusal of job to someone, sacking of someone else or a disciplinary action having been taken against a minister. It appears that the League was more interested in defaming the Congress and spreading calumny against it in public instead of legal action against it. Once, the League had set up an inquiry committee headed by the Nawab of Mirpur. In response to its findings, the Congress had refuted certain charges and given explanation for some other. But it was apparent that the League was more interested that these became talk of the town rather than resolution of the complaints. It should be noted here that even the governors who were sympathetic to the League and interested in finding fault with the Congress did not find much substance in these complaints. In fact more than one governor had praised the Congressmen for whom this was their first experience in governance.

For the League one major handle with which to beat the Congress was the latter’s language policy. Years ago, the Congress had adopted the spread of Rashtra Bhasha (Hindi) as one of its constructive programmes. The work of conducting Hindi training courses, started since then in South India through the Hindi Prachar Sabha, has been continuing peacefully till today. Every year, thousands of students in South India have been appearing for Hindi examinations. The propagation of Hindi was considered opposition to Urdu. Gandhiji had used the word ‘Hindustani’ in place of Hindi and encouraged the use of both Devnagari and Persian scripts for its writing. Jinnah was not proficient in either Hindi or Urdu. He had better command of English than his own mother tongue Gujarati. There were both Hindus and Muslims who spoke or wrote Urdu. But an impression was created that Urdu was the language of Muslims. In creating this impression, both the supporters and opponents of Urdu may have played equal role. In north India, most people used Hindi and Urdu words in their natural course. Experts of Urdu started picking and throwing out Hindi words from their daily use and the experts of Hindi did the same to the Urdu words. As a result, both the language suffered. That the Congress did not support Urdu is an impression that has remained embedded in the minds of even those Muslim intellectuals who did not believe in the politics of League. The language dispute became the prime instrument for spreading hatred between the two communities.

Another issue that was used by the League to spread canard against the Congress was the propagation of ‘Nai Taleem’ (New education system) by Gandhiji after 1937. Most educationists the world over had given favourable opinion on Gandhiji’s idea of imparting education through real life experience. However, Jinnah smelled in it an element of Hindu Raj. The teachers’ training college in Central Provinces named as ‘Vidyamandir’ became an excuse for this interpretation. Jinnah might not have even taken note of the fact that the president of the Hindustani Talimi Sangh was leading educationist Zakir Hussain and its secretary was a gentleman from Sri Lanka Arian William Aryanayakam.

The main factor responsible for the phenomenal expansion of the League, perhaps, was the support it got from the British government. The British government had supported the League, directly or indirectly, openly or secretly. The best instrument for an imperialist rule to sustain its system is the policy of ‘divide and rule’. Ever since the British government took the reign of power from the East India Company, this principle has constantly come in handy. They stuck to this principle unwaveringly for 90 years. They continued their game of two cats and one monkey for nine decades. They employed this policy most effectively to their advantage in the fourth and fifth decade of the twentieth century. The files in the offices of the British government are replete with such correspondence in which one of its officials has written to another advising him not be contemptuous towards Jinnah no matter to whatever extent he may be rude because he is our man.

The Congress was like a sore thumb to the British from viceroy Linlithgow (1887-1952) to Wavel (1883-1950) and from India secretary Zetland (1876-1961) to Amery (1873-1955) and if they had any excuse left to delay granting freedom to India it was the plea, ‘we cannot neglect such a large minority community.’ Though Britain was in a shambles due to the Second World War and the Liberals had come to power there, there were many among the rulers who had not shed their imperialist arrogance and deceit.

During the period 1937-1945, the relation between the Government of India and Jinnah was largely that between a patron and his protégé. Linlithgow (tenure 1936-43) had opined about Jinnah that he was representative of a minority community which could not survive without the support of the British government. From 1946 to mid 1947 the relation assumed the nature of a partnership. During the previous ten years Jinnah, with the support of the British rulers and by carrying out a mindless slander campaign against the Congress, increased League’s strength and his own reputation of being a clever politician. He knew at that time that he can survive only with the support of the British rulers and also the British rule can extend its span only with the support of the League. So by spitting venom at the Congress he could achieve three goals – challenge the reputation of the Congress, increase his own reputation and help the British rule’s longevity. Hence Jinnah was in a position to tell the Britishers that if they neglect the Muslims they would tilt towards the Congress; tell the Muslim majority states that if they support the League, the League would support them; and bluntly tell the Congress that it had no right to represent the whole country or that its president Maulana Azad is a lackey of the Congress. Let us examine what was Britishers’ dependence on Jinnah as the representative of Muslims in the last one and a half to two years in the Indian politics. Jinnah could assert that the Muslim representatives in the viceroy’s council must be from the Muslim League, Muslim ministers in the interim government can never be from any other party, or wherever the Congress ministries have resigned the charge of the government should be handed over to the Muslim League. Once he had gone to the extent of asserting the League’s equal right with the Britishers to administer the whole country!

When in 1935 the British government floated the idea of a federal government at the centre, Jinnah and other leaders of the League said repeatedly that a democratic system of governance was against the basic nature of India. Jinnah was interested only in central rule. He also said that no changes in the constitution should be suggested without the consent of the League.

When during the Second World War the government announced that the elections to the central assembly would be deferred, the League supported the move and even recommended that the elections should be cancelled.

Viceroy Linlithgow has noted in his diary dated October 5, 1939 that Jinnah met and thanked him for supporting his party!

Those smaller groups of minorities, seeing the government support to the League, started believing that it was in their interest to be with the League.

Even though rabid communal Muslim elements could not see Islam in Jinnah’s personal life, they ignored it and joined happily in his politics of communal hatred. They saw the same disdain, hatred and vengeance in their small and narrow drain as in the broader river. Thus the once hardcore nationalist Jinnah became one with communal elements and started giving them the benefit of all his Machiavellian intellectual faculties.

The British government needed a party to pit against the Congress. For this they cultivated the League. They also knew that the League cannot survive without their support. Jinnah too knew that the British government needs the League. Therefore, Jinnah continued to increase his demands. Sometimes both loathed the activities of each other. Yet since both understood each other’s utility they continued to support the other.

The last viceroy Mountbatten (1900-1979) had expressed the view that when the League was totally convinced that it would not get anything more then did Jinnah showed some sense and began practical negotiations regarding partition. To make him come to the sense, Mountbatten (tenure February 1947 – August 1947) showed Jinnah Churchill’s (1874-1965) message in which Churchill had reminded Jinnah not to forget the fact that the League’s existence was only because of the support of the British government. Churchill (tenure: 1940-1945, 1951-1955) had said: “Tell Jinnah that this is a life and death proposal worth grabbing with both the hands. I can say this by the oath of God that he should very well understand that he is a person who cannot exist without Britain’s support.”

Jinnah knew how to use his sharp brain in many ways. On May 1, 1947, two representatives of the American government, the head of the South Asian desk, Ronald A Hare, and the second secretary of the American embassy in India, Thomas V Will, came to meet Jinnah. The report of this meeting was sent by American secretary of state Marshall to American Charge-de-admin. According to this report, Jinnah flatly refused to live in a unified, undivided India under any circumstances. Jinnah’s argument was: “The formation of Pakistan is in the interest of America. Pakistan will be a Muslim nation. In case of an aggression by Russia, all the Muslim countries will meet the challenge unitedly. In this, all of them will expect America’s help. Jinnah further argued that Congress is a known enemy of Enemy and so will not come to the assistance of middle-east and Gulf countries. Pakistan would also need America’s help in combating ‘Hindu imperialism’.

In this entire process the Congress too was playing a supportive role wittingly or unwittingly. One of the reasons of this was that a party which had been waging a war against the government all these years was entrusted with the responsibility of running provincial governments. It carried out this responsibility fairly well. However, much of its energy got expended in this. This also exposed some of its members’ lust for power. The Congress had set up a parliamentary committee comprising Rajendra Prasad (1884-1963), Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel (tenure: 1947-1950) to help the party deal with the problems of governance in all the eight states where the party was in power. Ultimately, it was Sardar Patel who had to bear the main responsibility of this committee. Sardar’s sharp brain, administrative efficiency and his iron will contributed tremendously to strengthen the Congress party during this decade. At the same time, it was during this decade that Sardar’s image as ‘Iron Man’ also spread in the country. This great powerful personality was to strengthen not just the Congress party but the whole country in the next decade and even during the two and a half years after the independence. But unlike League, whose only programme was to oppose the Congress, to meet the challenge of the League was not the only agenda of the Congress. The Congress tried not just once but several times to understand and resolve the problems with the League. As the Congress president, Rajendra Prasad, Subhash Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru have had talks with the League. But every time these talks met with failure. The behind the scene activities of the League, of getting its demands met by the British government in instalments while keeping its cards close to the chest and demand more than what the opposition was expected to give, continued till the very last.

In the entire process, the ego clash between Jinnah and Nehru also played a substantial role. The rivalry and ego clash between political leaders tend to play a negative role in the history of nations.

As it is, the Congress did not pay as much attention to its constructive programmes as it paid to its political programmes of non-cooperation, civil disobedience movement, boycott and formation of ministries. As a result Congressmen missed the opportunity of establishing contacts with thousands of poor Muslim artisans which they could have done in the natural course through the work of khadi and village industries. As it is the Muslim leadership was restricted to representatives of the miniscule rich class and it had very few programmes for the common Muslim masses. So, if only the Congress had earnestly welcomed the constructive programmes and paid attention to promoting communal harmony, it would have true representative of the common Muslim masses. However, Congress leaders like Rajendra Prasad, Vallabhbhai and Kripalani did not pay as much attention to the problems of the common Muslim masses as they did on the work of Khadi. This is an important factor why the Muslim masses got alienated from the Congress.

It is true that nationalist Muslims were mostly with the Congress. But they too came from the upper middle class. Their activities too were only political and not constructive work. Gandhiji had repeatedly emphasised the need for the nationalist Muslim leaders to mix with the poor masses. But it is a fact that his appeal did not prove effective enough to make them give up their class characteristics and mix with the common masses. In addition to this, there was another turn of events that made divisive propaganda more effective. At the national level there were only a handful of nationalist Muslim leaders of which some died during the decade. The death of Hakim Ajmal Khan and Dr. Ansari put severe constraint to Gandhiji’s constructive efforts. Ali brothers, Saukat Ali and Mohammed Ali, may not perhaps be known as nationalist Muslims but they were surely national leaders. It was after their stars set on the national horizon that Jinnah’s star could rise and shine. Albeit both the Ali brothers had moved away from Gandhiji after the riots in Kohat (September 1924) in the Northwest Frontier Province. Thus among nationalist Muslim leaders only Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (1890-1988) had remained. Both of them were opposed to the partition till the end. However, Maulana’s reach could not extend to the Muslim masses. That leaves Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan. However, his activities were restricted to the Northwest Frontier Province where his influence was terrific. Both the Congress ministry and the British government had betrayed him at the end. The League took full advantage of this.

There were also some people in the Congress, who though remained with the majority view of the party, were sympathetic to the Hindus. They leaned more towards the Hindus following the Congress-League polarisation. Such groups used to become more active during tussle between Hindi and Urdu language, at times of communal riots and on the issue of cow slaughter. All this helped in widening the chasm. Jinnah used to cite the utterance of such Congressmen as the true face of the Congress party and say, “At least Hindu Mahasabha is honest enough that it does not attempt to hide its intention of establishing a Hindu nation; but the hypocritical Congress wants to achieve the same in the name of nationalism.”

Last but not the least strong reason was the upfront organization of communal Hindus and its blatant communal propaganda. Hindu elements had started forming a systematic organization since 1925 and begun their communal ideology. In his book “Hindutva”, V D Savarkar had propagated that there were two nations in this country – a Hindu nation and a Muslim nation. He said this more than once in his presidential addresses after becoming the president of the Hindu Mahasabha. The Muslim League said the same thing but in its Lahore session in 1940. One wonders if they were inspired by Savarkar to look at their own self in this fashion. Communal ideology, whether it belongs to one community or the other, is narrow, vengeful and rabid. Why not use the same arguments in one’s support even though these are being used by another community to propagate their ideology? More than the spread of ideology and philosophy it is the spread of venom in the society that has been more effective. It is the communal hatred that resulted in the partition of this country.

(*Nachiketa Desai is a senior journalist and grandson of eminent freedom fighter and Mahatma Gandhi’s personal secretary Mahadev Desai).

[the_ad_placement id=”sidebar-feed”]

You have made some decent points there. I looked on the web to find out more about the issue and found most people will go along with your views on this web site.