[the_ad_placement id=”adsense-in-feed”]

Entertainment is fine, but message and content do matter

By Rathin Das*

By Rathin Das*

The internal Emergency imposed in June 1975 became a period of hibernation for theatre activists as freedom of expression and civil liberties remained suspended, thus impairing all creative vocations.

[the_ad_placement id=”content-placement-after-3rd-paragraph”]

End of Emergency in 1977 was a liberating moment for many types of people, especially those who remained ‘prisoners’ of their conscience during the 18 months of ruthless authoritarianism. The re-opening of democracy in the country was an opportunity for academics, journalists, civil right activists and theatre enthusiasts to rejuvenate themselves in full form. The writers, however, were using their pen and paper to create prose and poetry during Emergency too but started making them public only after Indira Gandhi was dethroned in the elections of 1977.

Civil liberties had returned, but the ground reality had changed for the theatre groups. Suddenly, auditorium rentals went very high, sponsors for big shows were not forthcoming and not many new plays were written during the hibernation period.

Also read: Beyond sight and sounds : Relevance of theatre in modern times (Part 1)

It is said that necessity is the mother of invention. As if to prove this old saying correct, street theatre looked like the only option to fill up this void. Street theatre’s philosophy was very simple: “If the common man cannot come to theatre, then the theatre goes to him”. And the early protagonists of street theatre did exactly that.

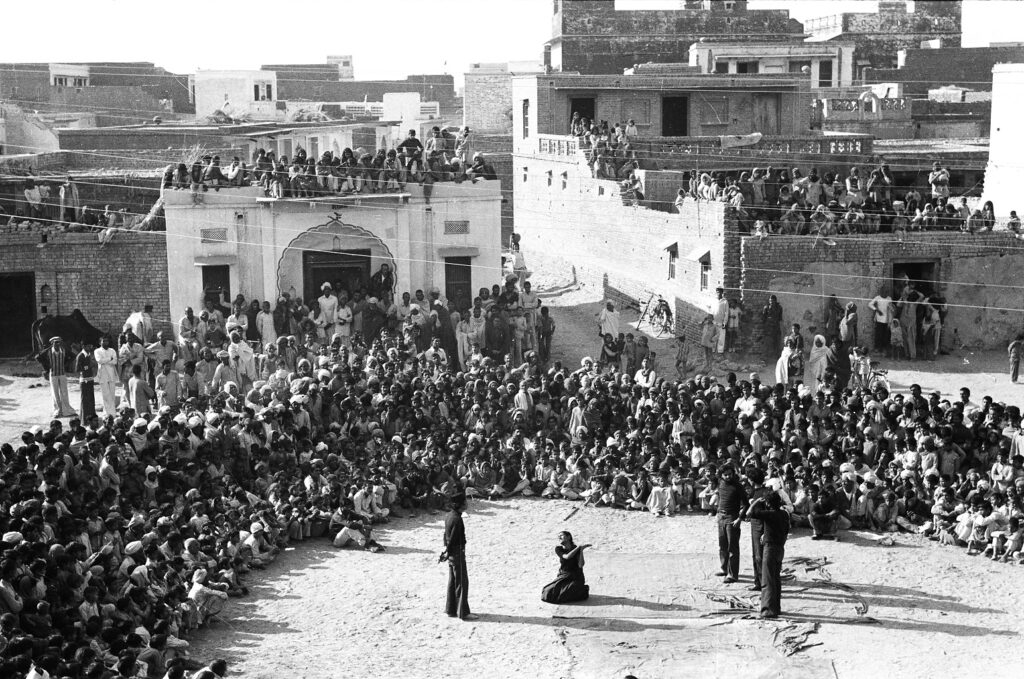

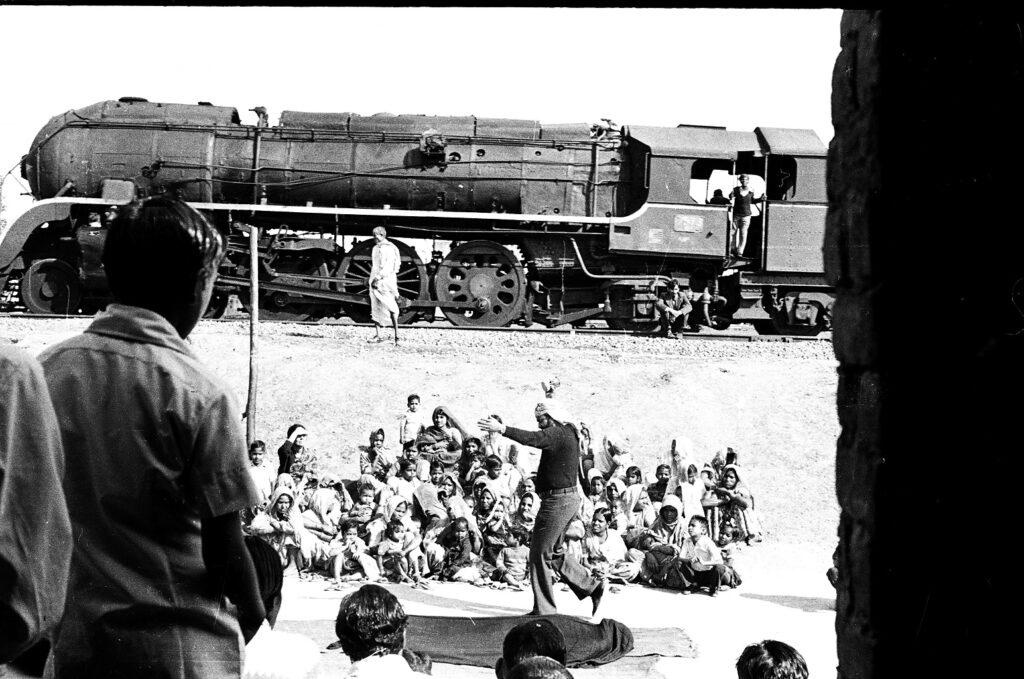

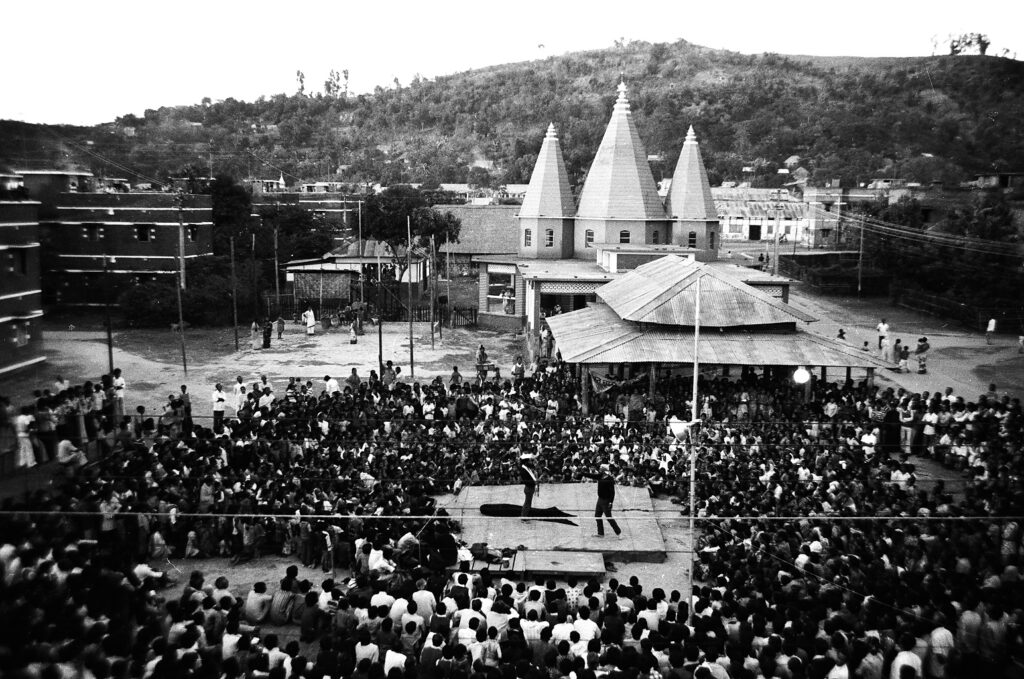

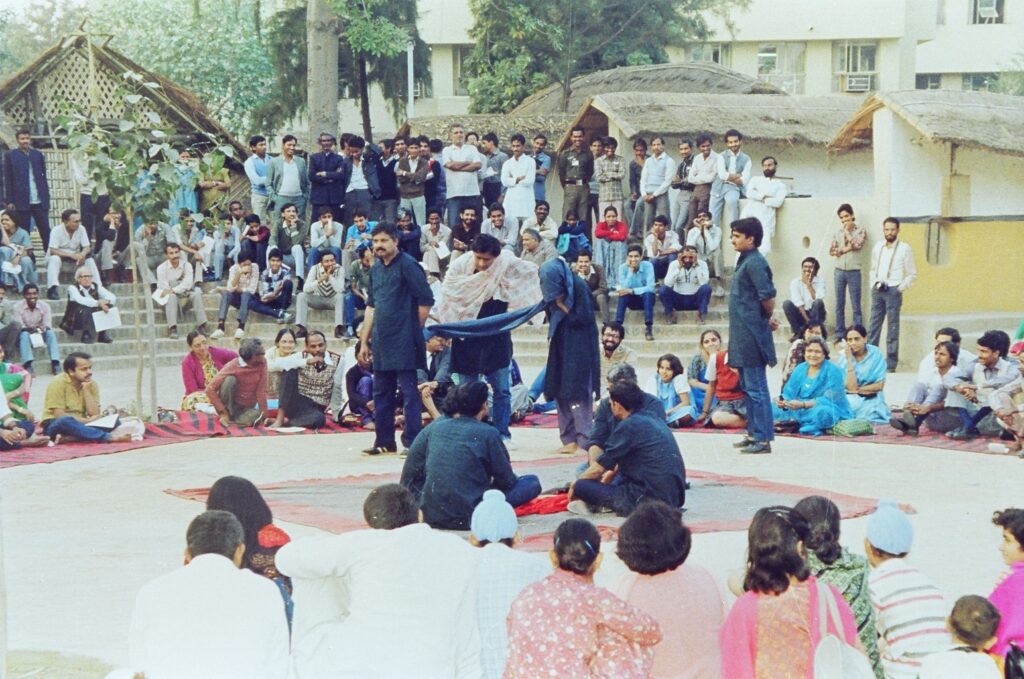

Thus, a group of less than a dozen people roamed the streets — literally, went to factory gates, their shanty colonies, its lanes and by-lanes, college grounds, city squares, bus stops, shopping areas or just about anywhere and performed small plays with instant engagements with the instantly gathered audiences.

Physical transportation of the theatre persons from the air-conditioned auditoria to the streets could be easy, but the form and content too of the plays required to be transformed to suit the situation of their new audience and their socio-economic mind-set.

This was a real challenge for the initial practitioners of street theatre which nevertheless became an instant hit as the new theatre movement coincided also with the people regaining their lost freedom of expression and civil liberties when the Emergency came to an end after Indira Gandhi was voted out in 1977.

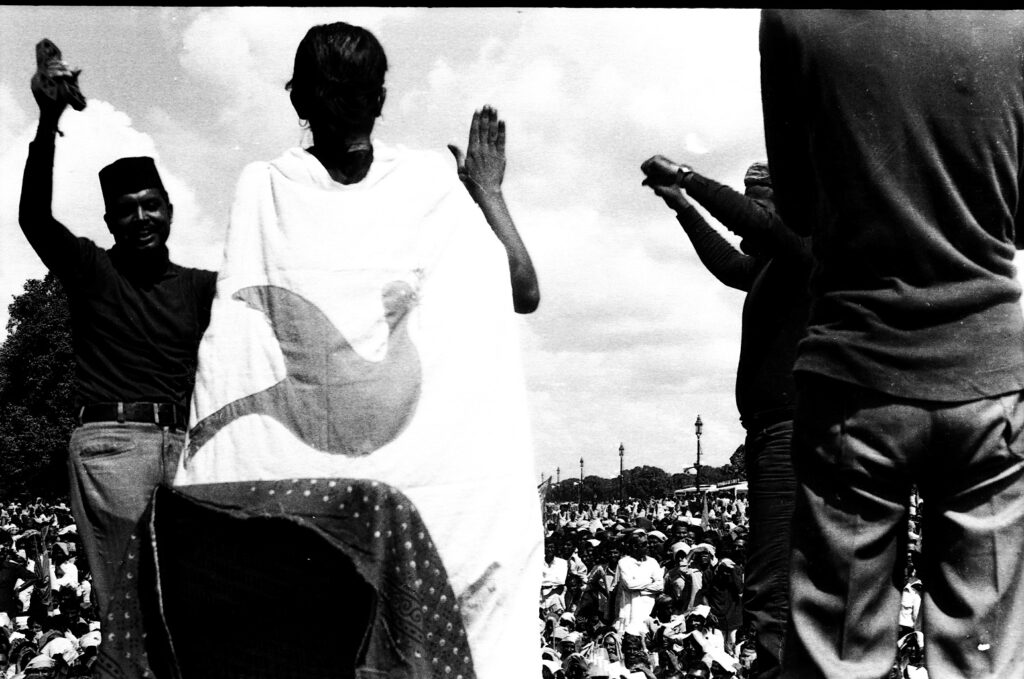

In the process of venting and reflecting the plight and aspirations of the people, this form of theatre ceased to be entertainment alone and became much more meaningful in terms of content riding piggy back on form in the theme’s journey to the mind.

As theatre moved to the streets, literally, it had to be in live contact with audience instantly and in real time with minimal scope for mistakes or misunderstanding. This is a tough task as the street theatre performers are surrounded from all sides and deprived of all advantages of the proscenium paraphernalia. Contrary to the earlier mistaken belief of many, street theatre is NOT any proscenium theatre performed on a makeshift stage in the absence of a proper auditorium.

Compulsion of being in live contact with the audience on all sides gave street theatre the responsibility to speak the ordinary people’s language without indulging in any academic jargons or un-necessary theorisations beyond the comprehension of the man on the street.

This responsibility of street theatre includes that the spectators should not carry the wrong message home. For example, if a scene dramatizes torture or harassment of woman by husband or employer, then the play should be structured in manner that the end message should NEVER be that such treatment is the norm. Condemnation of such behaviour should be inbuilt within the play’s storyline, as part of street theatre’s essential responsibility.

Probably as part of its social responsibility, the street theatre form has derived heavily from all traditional indigenous forms like the ‘Nautanki’, the ‘Madaari –Jambura’ (street magicians) or the acrobats or simply jokers.

In a multi-linguistic and multi-ethnic society like India where such open-air entertainment forms have existed for ages, no one can claim to have invented street theatre.

Several of the techniques of these ancient forms were imbibed into street theatre for long, but with the definite purpose to deliver a message to the select group of people gathered around.

Though the first priority of street theatre groups is to get the attraction of an impromptu audience by creating curious or unfamiliar sights or sounds or both, the immediate next job is to retain the attention of the gathering and deliver the message quickly.

Thus, if creating visual spectacles and attractive sound bytes are necessary for the form of street theatre, the next stage is more important as it is the content that would carry the message forward even before the audience decide to disperse.

Without relevant contents close to the people’s mind, merely creating visual spectacles with human bodies do not make any purposeful street theatre. So, by nature, street theatre has to relate itself, in form as well as content, to the burning problems facing the people.

The balance between form and content relating to contemporary issues are the keys to the success of street theatre as means of communication, but not without entertainment.

By its very nature, street theatre is devoid of any glamour usually associated with other performing arts but no spectator of this form can ever say that they were not entertained. The ability to deliver the message succinctly, in common people’s language, at his door-step, on subjects close to his heart and finding a solution within the limits of his thought process, has sustained the street theatre movement so long despite the communication revolution in the modern age.

That is why there is a lot of commonality among IPTA’s plays in 1940’s on freedom struggle and land rights, Jana Natya Manch’s street plays on workers’ rights and women’s issues in late 1970s, Samudaya’s (Karnataka) plays on social evils, Kerala Sashtra Sahitya Parishad’s plays on scientific attitude during the same period, Praja Natya Mandali’s (Andhra) plays on peasants’ struggles and the present-day plays by a Maharashtra group against superstitions.

Even in this age of digital technology and social media creating havoc in society, a group of tribal women in Gujarat regularly performs a street play to stop the practice of ‘witch-hunting’ in the state’s eastern tribal belt. The play is very effective in creating awareness against witch-hunting, but the tribal women who are performing this play for years remain illiterate themselves.

(Concluded)

*Rathin Das is a senior journalist. He was actively associated with late Safdar Hashmi and his street theatre group Jana Natya Manch

[the_ad_placement id=”sidebar-feed”]

Like!! Great article post.Really thank you! Really Cool.