South American camelids are unique indigenous mammals from the continent. ©Giada Connestari /FOOD4 LaStampa

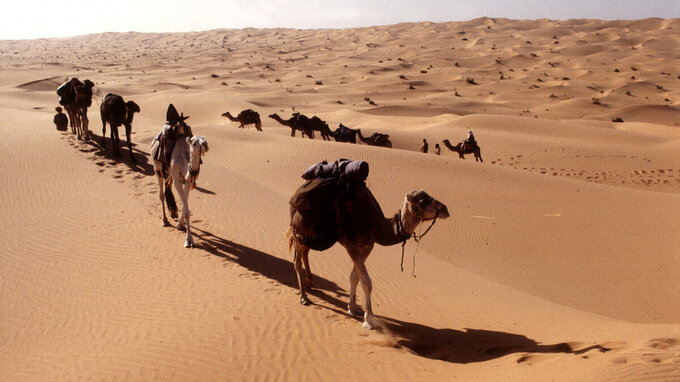

Camelids have been roaming the Earth since long before man arrived, and are referred to as the heroes of deserts and highlands for they can survive the toughest of climates. They live in over 90 countries and are crucial to the livelihoods of millions.

Camelids are a part of people’s cultures, livelihoods and identities. They are also working animals, supporting Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Their products contribute to nutrition, food security and economic growth all over the world.

Communities around the world depend on camelid products and services for their livelihoods. This is why recognition and support for camelids are crucial for community livelihoods and the environment, fostering sustainable jobs and equality.

In celebration of the International Year of Camelids 2024, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) is collaborating with partners to highlight the important role camelids play in community livelihoods and in building resilience to climate change – particularly in mountains and arid and semi-arid lands.

There are several different types of camelids and more of us in the world than one can count!

Here is an introduction to them!

The Bactrian camel

The Bactrian camel has two humps on its back. It is the largest living camelid, able to adapt to both climates of the desert and semi-desert regions.

Much like the dromedary camels, it can travel for long periods without food or water by using the fat stored in its humps and turning it into energy.

Do not confuse Bactrian camels with wild camels as the latter are a separate species only found in the remote desert areas between China and Mongolia.

Like all other camelids, a Bactrian camel is a sturdy and resilient creature, constantly serving people in times of need. Even in extreme climatic conditions, it continues to provide nutritious food and fibre. Like dromedaries, it is called a “ship of the desert” thanks to its ability to survive in challenging circumstances, which is why both Bractrian camels and dromedaries are crucial to nomadic and dryland communities.

The dromedary camel

It is the one-humped camel, and one can distinguish it by its long-curved neck and narrow chest. It has difficulty travelling through mountainous regions, which is why it is referred to as a camel of the plains. It exists in Africa and Asia and can travel vast distances like the Bactrian camels, surviving long periods without water. This may be why it makes the ideal companion through the vastness of deserts.

The llama

A tall, horse-shaped animal with a short tail is what it is. Its ears are rather long and slightly curved inward like bananas.

There are four million llamas today with half of them residing in Bolivia. Yarn made from their fibres is light but will keep one exceptionally warm.

Like other camelids, llama appeared in South America about 45 million years ago, and it is an integral part of the identity of many cultures and societies.

The alpaca

An alpaca has a long neck and legs and no top front teeth. Like other South American camelids, it has soft and padded feet, so it doesn’t damage the grasses that feed it.

It is a social creature and loves to be around other alpacas and other animals. It communicates with its body language so one can read its mood by just watching its movements and behaviour.

Spanning back to pre-Hispanic times, alpacas and their llama brethren, were the main working animals. They also provided fibre and meat to the communities. Alpacas and llamas are the only South American camelids to have been domesticated.

The guanaco

One of the largest terrestrial wild mammals in South America, one can identify it by its slender body and large pointed ears. Unlike a llama, its coat colour varies very little, from only a light to a dark shade of brown, with some white underneath.

Guanacos are speedy creatures, able to run from their predators. They can run about 35 miles an hour. That’s almost as fast as a tiger! Like other camelids, they are important to local communities for their fibre.

The vicuña

Vicuña is the national animal of Peru. It has a woolly brown coat on its back, while its chest hair is white. Many say that it provides some of the finest fibre in the world. It can live in cold temperatures regardless of its thin wool because its body traps the sun’s heat during the daytime keeping it warm throughout the night.

Vicuñas, like the other South American camelids – llamas, alpacas and guanacos- are also called New World camelids, and they are considered unique indigenous mammals from the continent. They are a spiritual and cultural part of Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ identities in the Andean highlands, much like how the Bactrian and dromedary camels are culturally and socially significant in the arid and semi-arid lands of Africa and Asia.

This is Camelids’ year! Now that one has gotten to know them, spread awareness of their untapped potential and see more of what they can do! Let the heroes of deserts and highlands help transform communities and cultures everywhere.

Source: the FAO News and Media office, Rome

– global bihari bureau