Asia-Pacific partnership creates news ‘centre of gravity’ for global trade: UNCTAD

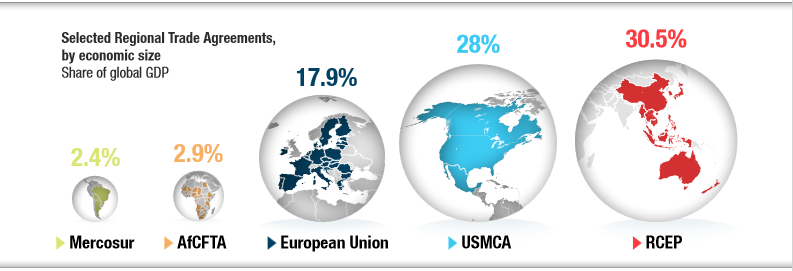

Geneva: A new Asia-Pacific free trade agreement set to enter into force on January 1, 2022 will create the world’s largest trading bloc by economic size, according to a United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) study published today.

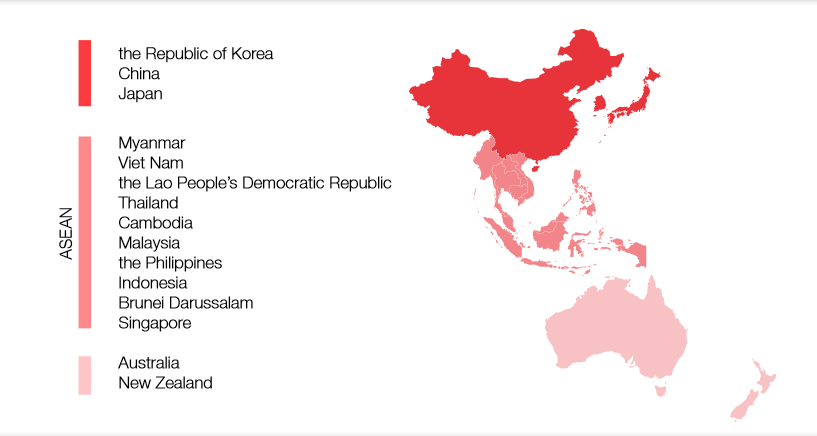

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) includes 15 East Asian and Pacific nations of different economic sizes and stages of development, representing around 30 per cent of world GDP. This makes it the largest trade agreement in the world as measured by the GDP of its members – almost one third of the world’s GDP. It was signed on November 15, 2020, and following ratification by at least six ASEAN member States and three non-ASEAN economies, will enter into force on January 1, 2022.

UNCTAD’s analysis shows that the RCEP’s impact on international trade will be significant. The agreement encompasses several areas of cooperation, with tariff concessions a central principle, which will eliminate 90 per cent of tariffs within the bloc. The concessions are key in understanding the initial impacts of RCEP on trade, both inside and outside of the bloc.

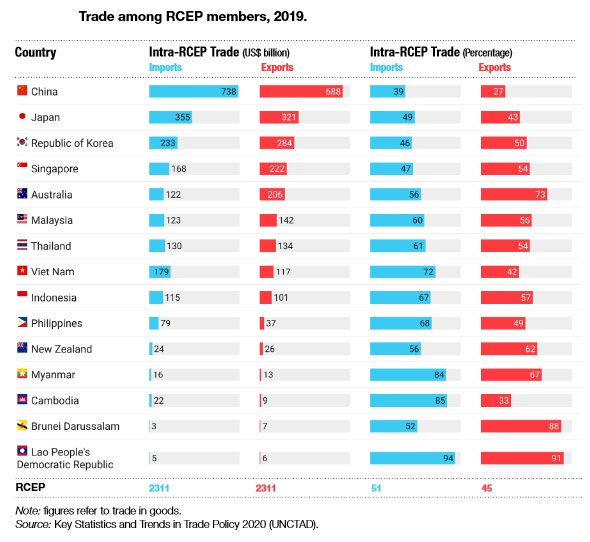

Intra RCEP-trade was already worth about US$ 2.3 trillion (2019) and this analysis shows that RCEP’s tariff concessions would further boost the intraregional exports of the newly formed alliance by nearly 2 per cent, approximately US$42 billion. This is the result of two forces: trade creation, as lower tariffs would stimulate trade between members, by nearly US$17 billion; and trade diversion, as lower tariffs within RCEP would redirect trade away from non-members to members, equivalent to nearly US$25 billion.

A key aspect of the RCEP is tariff concessions. The agreement is expected to ultimately eliminate tariffs on more than 90 per cent of goods traded within the bloc. In addition, it allows for significant discretion in the form of postponements. The implementation period is 20 years, it allows for exemptions for sensitive and strategic sectors, and some distinctions among members. The agreement goes beyond tariff concessions and encompasses other areas of cooperation to foster regional integration among its members. For instance, by setting up a time limit for the release of goods at customs, and by harmonizing rules of origins so as facilitate businesses to take advantage

A key aspect of the RCEP is tariff concessions. The agreement is expected to ultimately eliminate tariffs on more than 90 per cent of goods traded within the bloc. In addition, it allows for significant discretion in the form of postponements. The implementation period is 20 years, it allows for exemptions for sensitive and strategic sectors, and some distinctions among members. The agreement goes beyond tariff concessions and encompasses other areas of cooperation to foster regional integration among its members. For instance, by setting up a time limit for the release of goods at customs, and by harmonizing rules of origins so as facilitate businesses to take advantage

of the preferential terms of the agreement.

Most RCEP economies are already relatively open to trade, both because of their low WTO Most Favoured Nation tariffs and because of their participation in other regional trade agreements. In fact, prior to the RCEP, most of its member countries already had trade agreements in place, such as ASEAN.

Nevertheless, significant differences still exist among RCEP members. Australia, Brunei Darussalam, New Zealand and Singapore have already liberalized all, or almost all, trade originating from other RCEP members. In contrast, tariffs on imports from RCEP members are relatively higher for the Republic of Korea, Cambodia, and China. They are also substantial for Japan and Thailand.

There is wide heterogeneity in terms of trade flows within the RCEP members. For instance, while the top 3 exporters, China, Japan and the Republic of Korea account for nearly 60 per cent of intra-RCEP trade, Cambodia, Brunei Darussalam and Lao People’s Democratic Republic, only account for 1 per cent of these flows. However, the smaller members’ trade is relatively more dependent on RCEP. For Brunei Darussalam, Myanmar, and the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, more than 70 per cent of their total trade is intra-RCEP. In contrast, intra RCEP trade is more modest in the cases of China, Japan and the Republic of Korea.

In terms of economic sectors, the existing level of protection between RCEP members is higher in agriculture and lower for natural resources. Tariffs are also relatively important in the manufacturing sectors especially for Cambodia, China and the Republic of Korea.

Under the RCEP framework, trade liberalization will be achieved through gradual tariff reductions. Many tariffs will be abolished immediately, while others will be reduced gradually during a 20-year period. Remaining tariffs will be largely limited to strategic sectors, such as agriculture and the automotive sector, in which many of the RCEP members have opted out from any liberalization commitments.

Overall, since import tariffs between many RCEP members were already low, the agreement will mostly reduce these tariffs on imports from China, Japan and the Republic of Korea. For ASEAN members, along with Australia and New Zealand, the share of products with zero tariffs was already above 90 per cent, thus the main areas of opportunity for tariff reductions were with the other RCEP members. This general pattern is detailed by three main features of the concessions.

As in any other trade agreement, RCEP’s members are expected to gain to a varying extents from the agreement. Tariff concessions are expected to produce higher trade effects for the largest economies of the bloc, not because of negotiations asymmetries, but largely due to the already low tariffs between many of the other RCEP members. Indeed, the patterns of tariff concessions in RCEP show a degree of cooperation in the negotiation process, the report states.

– global bihari bureau

This blog is not just about the content, but also the community it fosters I’ve connected with so many like-minded individuals here