After 19 Years, Nipah Tests Bengal’s Preparedness

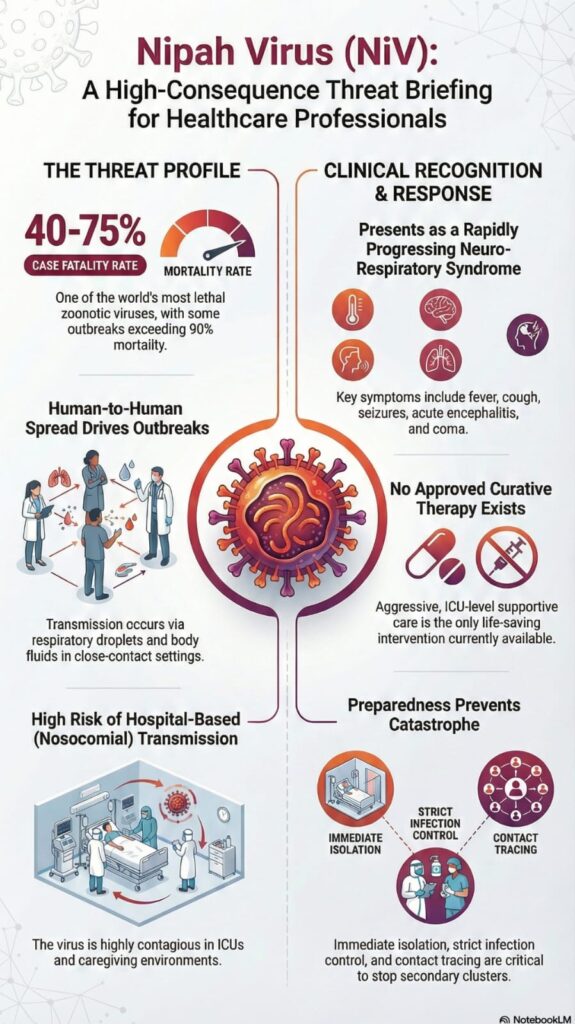

Kolkata: Nearly nineteen years after it last struck West Bengal, the Nipah virus, among the deadliest known zoonotic pathogens with a fatality rate reaching up to 75 per cent, has resurfaced, triggering a swift, multi-layered public health response shaped by lessons from India’s earlier encounters with the virus.

The warning signs emerged quietly but ominously at a private hospital in Barasat, North 24 Parganas, on the fringes of Kolkata. Two young healthcare workers—a male and a female nurse in their mid-twenties—suddenly developed severe illness. What began as high-grade fever and intense headaches rapidly progressed to seizures, altered sensorium, and acute respiratory distress. Both deteriorated with alarming speed and were placed on ventilatory support in isolation wards.

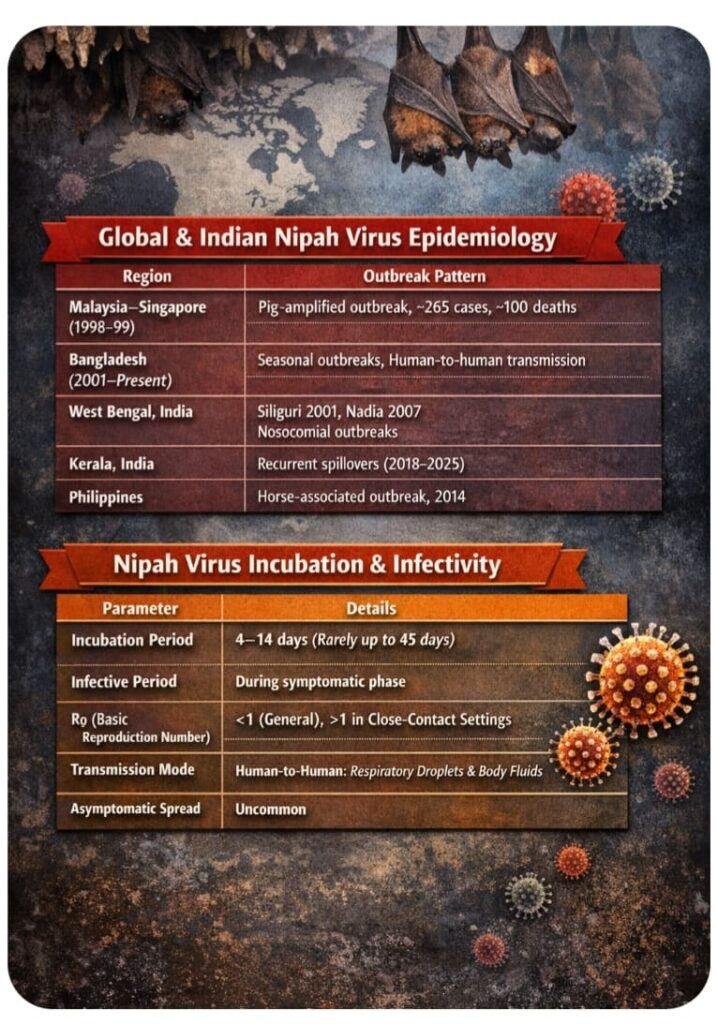

For experienced clinicians, the pattern was unmistakable: a cluster of encephalitis among hospital staff. In outbreak epidemiology, the near-simultaneous illness of unrelated healthcare workers is a red flag, suggesting intense exposure, possible early hospital-acquired (nosocomial) transmission, and the risk of amplification within a clinical setting. In the Indian context, such clustering immediately raises the spectre of Nipah virus—a pathogen notorious for turning caregivers into patients and spreading through close contact.

At that point, protocols kicked in like clockwork, shaped by Kerala’s hard-won experience with repeated Nipah outbreaks. The hospital’s infection control team isolated the patients, sealed affected areas, and initiated strict barrier nursing. Blood and throat swab samples were collected under enhanced biosafety precautions and rushed to the Virus Research and Diagnostic Laboratory of the Indian Council of Medical Research at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani (ICMR-VRDL, AIIMS Kalyani), a frontline sentinel in India’s infectious disease surveillance network.

On January 11, preliminary reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) results detected Nipah virus ribonucleic acid (RNA), triggering an immediate escalation across the state’s disease surveillance system. The samples were sealed and escorted under high-security protocols to India’s apex laboratory for such threats, the National Institute of Virology (NIV), Pune—mandated not only for confirmatory diagnosis but also for genome sequencing and viral lineage tracing, crucial to determining whether the strain represents a known Indian lineage, a cross-border linkage, or a fresh evolutionary spillover.

But Nipah waits for no one. Even before confirmatory results were available, escalation was lightning-fast. Outbreak mode was activated at the state level. Contact tracing expanded aggressively, with every hospital colleague, patient attendant, and family member exposed to the nurses identified and placed under active monitoring. Isolation wards were fortified across districts, and encephalitis alerts were issued to hospitals in North 24 Parganas, Nadia, and Purba Bardhaman, sharpening clinical vigilance and early referral pathways.

At the national level, there was no hesitation. Union Health Minister Jagat Prakash Nadda personally assured Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee of full central support. A National Joint Outbreak Response Team was deployed, bringing together experts from NIV Pune, AIIMS Kalyani, and wildlife and zoonoses specialists tasked with identifying the source—potentially fruit bats or contaminated date palm sap, both well-documented reservoirs of the Nipah virus.

As the two nurses remain critically ill on ventilators, the nation holds its breath. The source of infection remains uncertain. Did the virus spill over directly from bats? Was there an undetected human case? One nurse had recently travelled near the Bangladesh border, while the other came from distant districts, complicating epidemiological reconstruction. Investigators are racing against time to close these gaps before secondary transmission can take hold.

West Bengal has faced Nipah before—in Siliguri in 2001 and again in 2007, with deadly consequences. This time, authorities point to the speed of bedside clinical suspicion, laboratory escalation, and coordinated response as evidence that institutional memory is functioning as intended.

The threat remains real. Nipah spreads through close physical contact, respiratory droplets, and contaminated food, and even a single lapse can ignite secondary clusters. Yet across hospitals, laboratories, and surveillance units, the system remains on high alert.

The threat remains real. Nipah spreads through close physical contact, respiratory droplets, and contaminated food, and even a single lapse can ignite secondary clusters. Yet across hospitals, laboratories, and surveillance units, the system remains on high alert.

India is confronting the virus once again—armed not with a vaccine or a specific cure, but with preparedness, precision, and experience forged in earlier battles.

By

By