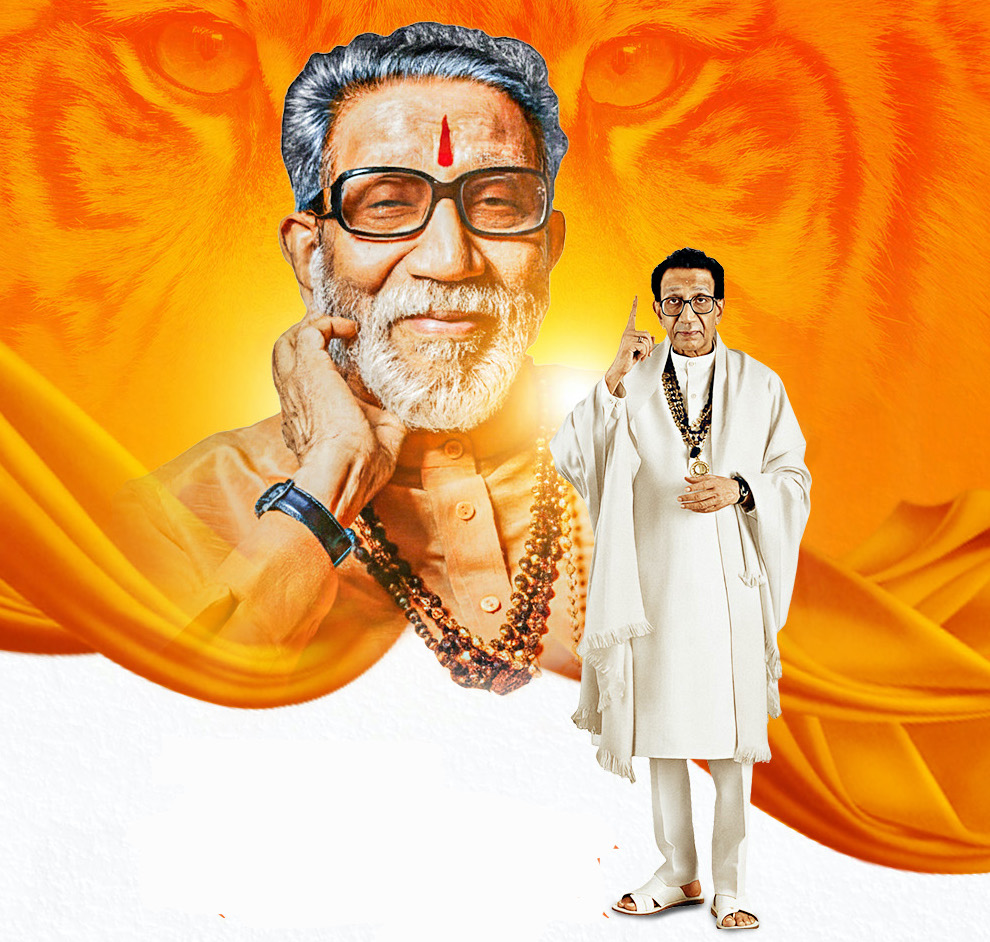

Bal Thackeray (23.1.1926 - 17.11.2012) Photo source: Facebook

By Vidyadhar Date*

By Vidyadhar Date*

Revisiting the Thackeray Paradox

I was present at a meeting in Prabhadevi, Mumbai, in 1989 during the launch of the Shiv Sena daily Saamna. On that occasion, Mr Bal Thackeray made a statement that revealed much about his political outlook. Addressing his followers, he openly urged them to engage in corruption. He said that the Congress had made money through the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation for years and that now the Shiv Sena would do the same.

There were many such troubling aspects of his thinking and actions. For this reason, one must approach his legacy with caution during the centenary of his birth, even as he is being projected by many as a heroic figure.

There is also a serious problem with sections of the upper class that openly supported his most undemocratic methods. At heart, these sections have often been uneasy with democracy itself and more comfortable with personality cults. I recall the foreword written by senior journalist Vir Sanghvi for Sujata Anandan’s book on the Shiv Sena, in which he compared Mr Thackeray to a superstar, specifically mentioning Amitabh Bachchan and Rajesh Khanna.

Sanghvi’s own record as a journalist was mixed. For months, he ran a column devoted almost entirely to praising food in five-star hotels, without addressing the immense food-related problems faced by ordinary people.

Mr Thackeray maintained an open alliance with capitalists and admired what he called five-star culture, which he consistently glorified. His trade unions were known to indulge in corruption, a fact confirmed by many personnel managers. These unions also worked to undermine democratic institutions and left-wing politics. That culture of luxury continues even today. Ironically, the rival Shiv Sena faction led by Eknath Shinde recently lodged its newly elected corporators at the five-star Taj Lands End hotel in Bandra.

The Shiv Sena was instrumental in introducing five-star culture into mainstream politics. Party meetings were frequently held in luxury hotels—something no political party had done before. By contrast, Congress Party deliberations were often conducted in modest venues such as the New Zealand Hostel in Aarey Colony. There was also widespread discussion years ago that Mr Thackeray had wanted to purchase the Sea Rock Hotel in Bandra after it was shut down following the bomb blasts.

On one occasion, Mr Thackeray urged Marathi people to become entrepreneurs and open five-star hotels. Turning to Mr Manohar Joshi, he remarked that Joshi’s establishment was only a four-star one and that what was really needed were five-star hotels. He expressed admiration for the Oberoi chain. It did not occur to him to propose low-cost accommodation for the Marathi manoos visiting Mumbai.

More damaging than the culture of violence directed against democratic forces was the lowering of political discourse to alarming depths—through abusive language, ethical degradation, and contempt for democratic values and serious debate.

I myself was a victim of Shiv Sena violence in the 1970s. I was assaulted, and my spectacles were broken. However, in other cases, the consequences were far more serious.

Last week, senior Marathi journalist Sandeep Acharya recalled an incident from the period before the 2004 elections. He had written in the widely circulated daily Loksatta, criticising the Shiv Sena for failing to fulfil its election promises. In response, Saamna carried Mr Thackeray’s photograph on its front page along with an extraordinary call: “Disembowel this man, take out his intestines.”

The threat was taken seriously. Acharya was deeply worried, as were many others. Gopinath Munde, then a Bharatiya Janata Party leader allied with the Shiv Sena, cautioned Uddhav Thackeray against allowing such an incident to occur on the eve of elections.

It is worth noting that Acharya himself belongs to the ideological right. His father, Ashok Acharya of Maharashtra Times, was a staunch Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh supporter. Even today, Sandeep Acharya remains a Shiv Sena admirer.

Like most political personalities, Mr Thackeray had certain positive qualities. He was a capable cartoonist and possessed a sense of humour. He gave Marathi people a sense of identity and raised his voice against discrimination in employment faced by the Marathi manoos. That discrimination did exist, and I witnessed it during the 1960s.

Linguistic identity remains important today, especially in an era when misleading ideas are promoted in the name of nationalism. However, Mr Thackeray pursued this agenda in a profoundly undemocratic manner.

He was undoubtedly a popular orator. Yet, when compared with an earlier great speaker, such as S.A. Dange, the Communist leader, the contrast is stark. Dange could appeal to both ordinary workers and serious intellectuals. He had a deep understanding of international politics, culture, and literature—an intellectual range far beyond that of Mr Thackeray.

Regional politics elsewhere, particularly in Tamil Nadu, evolved in a more progressive direction. In April 2025, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin announced that a statue of communist ideologue Karl Marx would be installed in Chennai to honour his contribution to labour rights and socialist philosophy. The statue is planned at the entrance of the Connemara Public Library, recognising Chennai’s history as a centre of labour movements.

As Mr Bal Thackeray’s centenary is commemorated, it is necessary to look beyond the personality cult and examine the political culture he fostered—one marked by luxury, intimidation, and a sharp decline in democratic ethics, alongside a limited but undeniable appeal rooted in linguistic identity.

*Senior journalist. Views are personal.