Our planet on fire – Part 10

Future wildfire risk

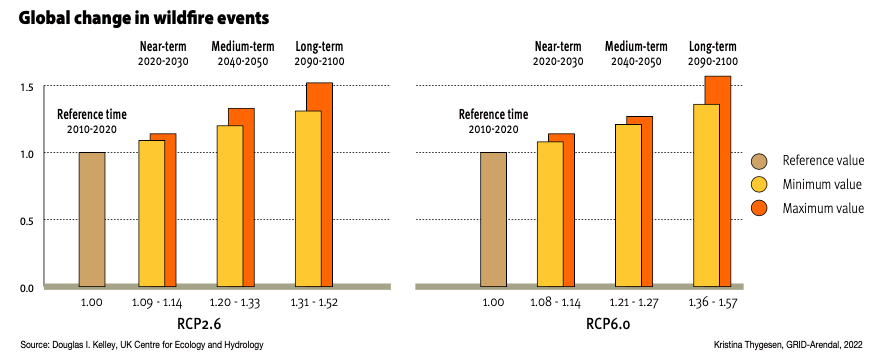

Human-induced climate change is increasing the incidence of wildfires around the globe. But how bad is it likely to get? It is hard to say exactly because even though the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report confidently predicts an increase in extreme fire weather (IPCC 2021), other complex interacting processes influence wildfire risk. However, despite the limitations of current global wildfire models to capture all these interactions, the available information illustrates an increasing risk in many locations. For example, an upward trend in the burnt area (despite large interannual variability) is evident in the forests of eastern Australia, Siberia, Canada, and the western United States. Similarly, the figure below illustrates a predicted increase in extreme fire events between now and the end of the century under different future climate scenarios.

It is well established that exposure to wildfire smoke causes adverse human health impacts. A recent study examined the relationship between mortality and wildfire-related PM2.5 in 749 cities across 43 countries from 2000 to 2016. The authors found that 0.62 per cent of deaths were attributable to acute exposure to wildfire smoke (10 μg/m3 increase in the 3-day moving average of PM2.5). This equates to an estimated annual death toll of 33,510 people across the 749 cities. Wildfire smoke can also make people more susceptible to other respiratory illnesses, including COVID-19. A recent study from the western United States found that over 19,700 cases of COVID-19 and 748 deaths were attributable to increased PM2.5 from wildfire smoke.

In recent years, wildfires have been responsible for up to 50 per cent of the PM2.5 air pollution in the western United States – a substantial increase over the last decade. A related study estimated that 82 million people in this region would be affected by “smoke waves” (two or more days of unsafe PM2.5 levels related to wildfires) by the middle of the 21st century. Without increased fuel management, exposure to wildfire smoke will continue to increase, especially as more and more people move into areas adjacent to wildland (estimated at one million new homes every three years across the USA). Livestock is also increasingly affected by smoke. A survey of farmers carried out after the 2020 wildfire season in the western USA indicated that on top of direct losses to fire, sheep, cows, and goats experienced a range of impacts. These included poor weight gain, reduced conception, decreased milk production, and cases of pneumonia.

Even with the most ambitious efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions, the planet will still experience a dramatic increase in the frequency of extreme fire conditions (see the above figure). This means that by the end of the century, the probability of wildfire events similar to Australia’s 2019–2020 Black Summer or the huge Arctic fires in 2020 occurring in a given year is likely to increase by 31–57 per cent. Wildfires are already affecting the health of millions of people and animals, straining national and local economies, and increasing economic inequality. As wildfires become more frequent, the impacts will increase.

Excerpts from Spreading like Wildfire – The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires. A UNEP Rapid Response Assessment. Nairobi. United Nations Environment Programme (2022).

– global bihari bureau