43 Days on the Brink

How the Longest Shutdown in Modern History Nearly Broke American Air Travel

Washington: The 43-day federal government shutdown that ended on November 12, 2025 — the longest in modern U.S. history — exposed just how thin the margin has become between normalcy and chaos in the nation’s aviation system.

It began, as so many do, with a failure to pass spending bills by October 1. What made this one different was Speaker Mike Johnson’s decision to send the House of Representatives into a 54-day recess, insisting the Senate needed to “act first,” and the Senate’s refusal to accept fourteen consecutive Republican continuing resolutions unless they preserved Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace subsidies and reversed scheduled Medicaid cuts. Partisan messaging quickly spiralled: President Donald Trump repeatedly accused Democrats on Truth Social of “holding the government hostage” and “choosing illegals over Americans.” Independent fact-checks confirmed the Democratic demand concerned only legally enrolled ACA users, not undocumented immigrants, but the distortion fueled weeks of deadlock.

By the third week, the consequences were no longer theoretical.

Nearly 750,000 federal employees were furloughed or working without pay — including every Transportation Security Administration (TSA) screener, almost every Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) air-traffic controller, and thousands of Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated $16 billion in lost wages and an $18 billion hit to fourth-quarter gross domestic product (GDP) — roughly 0.1 per cent per week, with a persistent 0.02 per cent drag expected to linger — while more than 60,000 private-sector jobs vanished or were threatened. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) verifications stalled for roughly 40 million recipients; the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) paused in multiple states; the Small Business Administration (SBA) left more than $2 billion in loans in limbo. The University of Michigan consumer-sentiment index recorded its sharpest year-on-year November plunge in decades.

Aviation felt the pain fastest and hardest.

The FAA was already 3,000 controllers below authorised staffing. During the shutdown, retirements and resignations spiked from the normal 4 per day to 15–20. By early November, the agency was forced to impose phased flight caps at 40 major airports: 4 per cent starting November 7, rising to 6 per cent on November 11, with 8 percent and 10 per cent phases on standby, ready to activate if staffing triggers — the FAA’s key safety metric — exceeded emergency thresholds like the 81 events recorded nationwide on November 8. Internal memos reveal how close the system came to the next step: at one major hub, certified controller staffing fell from 81 on Friday, November 8, to just three by Sunday, November 13. The FAA openly discussed closing entire air corridors — a step never before taken domestically for staffing reasons alone.

Ground stops blanketed Newark Liberty, LaGuardia, Chicago O’Hare, Los Angeles International, and Atlanta Hartsfield–Jackson. Airlines for America (A4A), the industry’s largest trade association, later calculated that 71 per cent of all delays during the shutdown were directly attributable to air-traffic-control (ATC) shortages. More than 5.2 million passengers on its member carriers alone faced significant delays or cancellations; system-wide losses peaked between $285 million and $580 million per day. Had the shutdown lasted another week, it would have collided with the pre-Thanksgiving surge of 31 million travellers.

Then came November 4.

A United Parcel Service (UPS) McDonnell Douglas MD-11 freighter crashed on takeoff from Louisville Muhammad Ali International Airport, killing all three crew members and 11 people on the ground when the number-2 engine and pylon separated. Within 48 hours, the FAA issued an emergency airworthiness directive grounding the entire U.S. MD-11 fleet pending inspections — instantly removing roughly 300 daily UPS wide-body flights. Worldport in Louisville, the company’s global hub, went from processing 400,000 packages an hour to a fraction of capacity. Memphis, Dallas–Fort Worth, and Ontario felt the shockwave. Medical supplies, auto parts, and holiday e-commerce shipments backed up for weeks.

Furloughed National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigators and unpaid FAA engineers worked in what one internal report called “a finely balanced triage.” Safety was preserved, but efficiency collapsed. In the days that followed, the city of Louisville gathered at the Big Four Bridge — the iconic pedestrian span over the Ohio River — for a vigil lit in yellow, UPS’s corporate color, where hundreds stood in silence at 5:14 p.m., the exact moment of the crash, their candles flickering against the November chill as a reminder of lives lost amid the machinery of commerce.

The fallout rippled far beyond U.S. borders, turning a domestic political standoff into a global supply chain tremor. At major ports like Los Angeles and Long Beach, CBP officers — though deemed essential and funded by user fees — were stretched thin, leading to dwell times for imported containers that ballooned by 15 to 20 per cent. Asian manufacturers, reliant on just-in-time shipments to American factories, faced cascading shortages: automotive parts from Mexico under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) sat idle for days awaiting secondary approvals from furloughed agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). European exporters rerouted perishables through Canada, incurring 5 to 10 per cent higher freight costs, while Chinese suppliers reported a 10 per cent drop in U.S.-bound volumes, forcing them to pivot to alternative markets.

Logistics firms worldwide scrambled to buffer the chaos, with companies like Maersk and Expeditors issuing alerts for importers to front-load shipments and pad timelines by three to five days. Global trade models from Oxford Economics projected a 0.3 to 0.5 percentage point drag on world GDP if the shutdown had stretched another week. In a world still scarred by pandemic-era bottlenecks, this wasn’t just a hiccup — it was a stark reminder that when Washington pauses, the gears of global commerce grind slower, often for months after the lights flicker back on.

Many who lived through the 35-day shutdown of 2018–2019 thought they had already seen the worst. Both that episode and the one just ended unfolded during Donald Trump’s presidency — the first triggered by his demand for border-wall funding, the second by a Republican refusal to extend ACA subsidies without broader spending concessions — yet the parallels ended there. Back then, unpaid TSA screeners called in sick in droves, lines at airports stretched for hours, and the country watched in disbelief as Coast Guard families lined up at food banks. That episode cost the economy roughly $11 billion and left scars that took months to heal. Yet the 2025 shutdown proved far more punishing. It was not partial, as the earlier one had been, but total — every agency unfunded from day one. The damage to aviation was two to three times greater: formal flight caps instead of voluntary absences, a deadly cargo crash layered on top of the chaos, and a system pushed to the edge of outright failure rather than merely strained. Where 2019 had been a warning shot, 2025 felt like the bullet itself.

The difference lay in timing and exhaustion. The workforce that absorbed the blow in 2025 was the same one that had never fully recovered from 2019, still short thousands of controllers and still carrying the institutional memory of missed mortgage payments and maxed-out credit cards. Six years on, the margin for error had vanished. One senior FAA official put it bluntly in an internal briefing leaked after the crisis: “In 2019, we bent. In 2025, we almost broke.”

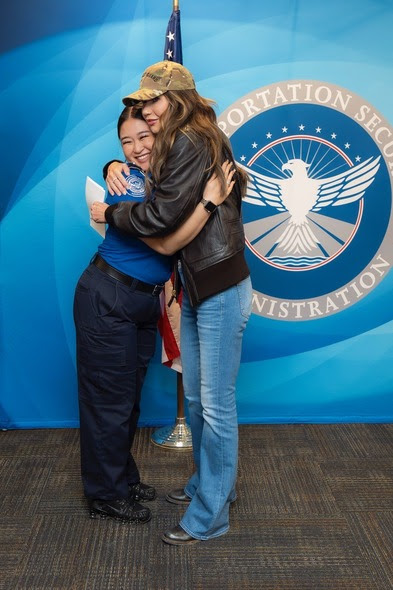

Amid the strain, one moment of grace: the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) awarded $10,000 perfect-attendance bonuses — funded from fiscal year 2025 carryover money — to more than 270 TSA officers at Boston Logan and, in a televised Houston ceremony on November 13, to officers like Reiko Walker and Ashley Richardson. President Trump proposed the same for air-traffic controllers. The gestures drew rare bipartisan praise even as ethics offices reviewed compliance with gift rules.

Resolution finally came when seven Senate Democrats and one independent (caucusing with Democrats) joined Republicans, while six House Democrats crossed the aisle. The bill, signed November 12, restored funding, guaranteed back pay, suspended reductions-in-force (RIFs) until January 2026 — after the Office of Personnel Management had slashed the usual 60-day notice period to 30 and federal unions won preliminary injunctions in the Northern District of California — and punted the ACA/Medicaid fight to December.

President Trump wasted no time declaring victory. Moments after the signing, the White House released a triumphant statement titled “THE DEMOCRAT SHUTDOWN IS OVER!” framing the 43-day impasse as a Democratic refusal to negotiate. The President’s first full week back in operation was a carefully choreographed celebration of normalcy restored: a dramatic flyover and surprise drop-in at the Washington Commanders–Detroit Lions game, where he joined the broadcast booth; an announcement of $2,000 payments to Americans funded by tariff revenue; a wreath-laying ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery on Veterans Day; interviews with Laura Ingraham, Bev Turner, and Pat McAfee; and the marking of the Marine Corps’ 250th birthday. On November 14 he signed, alongside First Lady Melania Trump, an executive order titled “Fostering the Future,” which she described as creating “a comprehensive network connecting federal departments and agencies, private sector businesses, higher-learning institutions, and charitable organisations” to support American youth. Vice President Vance, meanwhile, attended the Marine Corps birthday gala, visited wounded warriors at Walter Reed, and joined Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. at the Make America Healthy Again Summit.

For millions of travellers still stranded by cancelled flights and for the controllers and screeners who had worked six weeks without pay, the White House victory lap felt jarring. Yet the cameras captured the contrast perfectly: while the President tossed footballs from the owner’s box and signed ceremonial orders in the Oval Office surrounded by children, the FAA’s own internal logs showed the nation’s airspace only returned to full capacity on November 17 — five days after the government technically reopened — triggered by the bare-minimum staffing of six controllers on Friday, eight on Saturday, and one lone controller on Sunday at critical facilities.

NextGen modernisation, hiring pipelines, and deferred airport maintenance will take months to unwind. Analysts place cumulative airline and travel-industry losses in the tens of billions.

For the workers who kept the system from tipping over — the three controllers on that Sunday shift, the TSA officers who never missed a day without pay, the investigators who flew to Louisville on their own dime — the shutdown is over. For the rest of the country, the question lingers: how close did America come to a systemic aviation failure caused not by weather or terrorism, but by its own elected leaders?

On November 17, 2025, the answer feels uncomfortably close.

– global bihari bureau