Green industrial policies are key if developing countries are to adapt to the stresses of a changing climate, says UNCTAD

Geneva: The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has warned that the push to liberalize trade in environmental goods and services will benefit mainly exporters in developed countries and constrain fiscal space in developing countries.

Geneva: The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has warned that the push to liberalize trade in environmental goods and services will benefit mainly exporters in developed countries and constrain fiscal space in developing countries.

The second part of the Trade and Development Report of UNCTAD, which was launched ahead of the upcoming United Nations Conference of the Parties 26 (COP26) on October 28, 2021, estimates that developing and least developed countries will lose $15 billion per annum in tariff revenue if this approach is pursued. It cautions against a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) that would only compound the damage from climate change in many developing countries by undermining their export capacities and making structural transformation more challenging. (The first part of the Trade and Development Report 2021 report was released in September)

Estimates indicate that annual climate adaptation costs in developing countries could reach $300 billion in 2030 and, if mitigation targets are breached, as much as $500 billion by 2050. But current funding is less than a quarter of the 2030 figure and the report warned that relying on private finance will not deliver on scale or to the countries most in need.

According to the report, what is needed is a transformative approach to climate adaptation, with advanced economies ensuring that multilateral institutions can support developing countries to manage the pressures from a changing climate without compromising their development goals.

Outlining reforms of the international financial system to get more climate adaptation funds flowing to developing countries, the report recommends that reforms should focus on the following:

- Official Development Assistance (ODA) commitments need to be met and exceeded, to increase the proportion of additive finance designated for climate change adaptation and resilience building. If the G7 countries had met the 0.7% ODA target in 2020, an additional $155 billion would have been available to meet development goals.

- Debt relief and restructuring for developing countries should be put firmly on the climate agenda. An obvious place to start would be the debt of the V20 group of climate-vulnerable countries but the link between the climate and debt crises highlights the need for more systemic reforms to the international debt architecture.

- The multilateral development banks need additional capital to fund climate adaptation through grants and extremely concessional loans. These could be financed by a green bond and a tax à la Tobin, or through the repurposing of fossil fuel subsidies.

- Green bond markets are one way to help raise long-term financing. Yet regulatory standards lag the growth of these market and greenwashing is rife. Given the scale of the challenge, the regulatory framework for the green bond market needs to be supported by corresponding levels of financing and staffing, at national and international levels.

UNCTAD Secretary-General Rebeca Grynspan said: “Fulfilling the $100bn a year pledge for the Green Climate Fund is a must at Glasgow. But aligning ambition and action will require a concerted reform effort at the multilateral level to ensure adequate funding for developing countries to adapt to the worsening impacts of ever-increasing climate change. Climate change has no borders, so our strategy to adapt to it must be globally coordinated.”

The report worries that many of the reform initiatives gaining momentum in the international trading system continue to downplay the deep divisions and asymmetries that structure the contemporary global economy.

It suggests that national trade policy can at best play a complementary role in achieving climate goals while poorly designed international trading rules will hinder a green transformation. It stated that expanded policy space with legal tools such as waivers and peace clauses at the World Trade Organization (WTO) can better help developing countries to develop capacities to move towards climate goals.

Asserting that green industrial policies are key if developing countries are to adapt to the stresses of a changing climate, the report points out that developing countries were already suffering relative economic losses three times greater than high-income countries due to climate-related disasters.

It reveals that 2021 has been another year of extreme climate events; more intense heatwaves, increasingly powerful tropical cyclones, prolonged droughts and higher sea levels are unavoidable, with rising global temperatures bringing with them ever greater economic damage and human suffering.

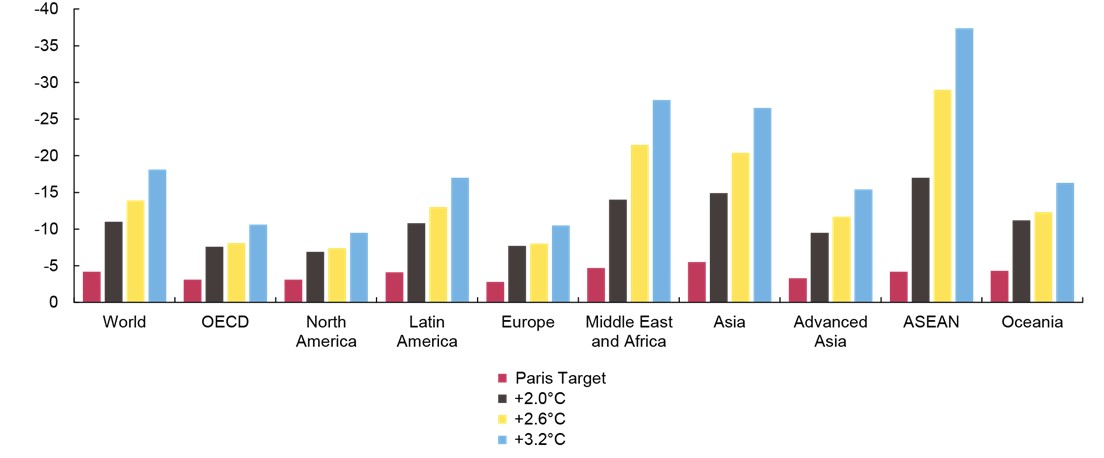

In many developing countries vulnerability to economic and climate shocks are compounding each other, locking countries into an eco-development trap of permanent disruption, economic precarity and slow productivity growth. The greater the rise in global temperatures, the greater the damage to countries in the South (see Figure).

Mid-century GDP losses by region generated by global warming

The report calls for a transformative approach to climate adaptation, with large-scale public investment programmes to adapt to future as well as current threats, and green industrial policies to drive growth and job creation.

UNCTAD said critical green technologies should be classified as public goods and their access made affordable for all. The international community could support initiatives to transform rules governing intellectual property rights, expanding flexibilities in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) for developing countries in relation to climate-related goods and services, such as through a WTO ministerial declaration on TRIPS and climate change.

This could provide a basis for innovative mechanisms for promoting access to patent-protected critical green technologies to support adaptation and mitigation efforts, it stated.

– global bihari