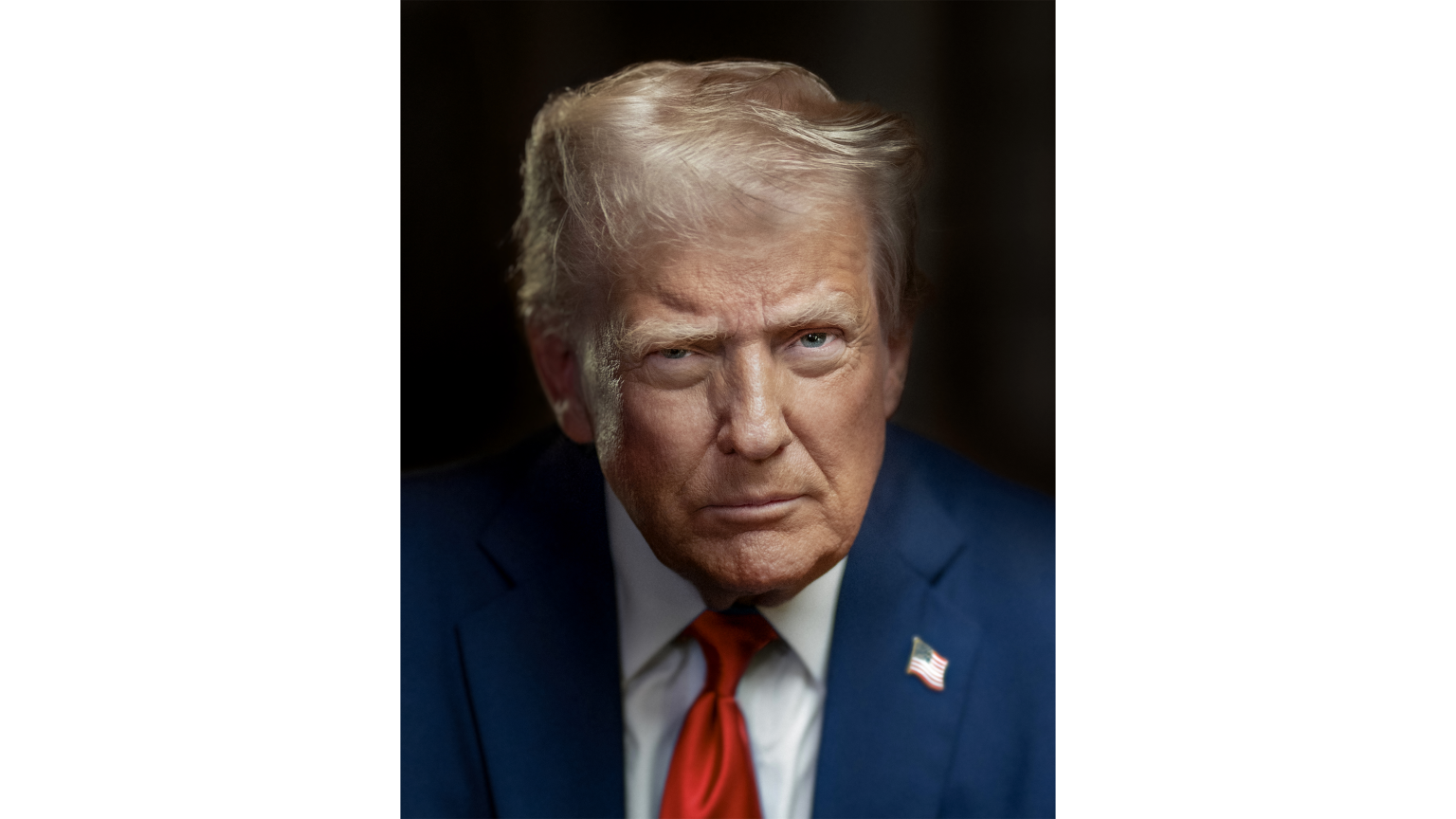

Donald J. Trump. Photo source: White House

Trump Orders US Exit from 66 Global Bodies, Tightens Grip

America Recasts Global Role Under Trump’s New Orders

Washington: President Donald Trump on January 7 ordered the United States to withdraw from 66 international organisations, a move that follows days of forceful U.S. action in Venezuela and marks a sharp turn in American foreign policy. The decisions represent one of the most significant reconfigurations of U.S. foreign policy architecture in recent decades.

Acting through a Presidential Memorandum and a series of Executive Orders issued on January 7, 2026, Trump moved to redraw the boundaries of America’s engagement with the international system while asserting a more forceful use of U.S. power in the Western Hemisphere.

The withdrawal order directed all executive departments and agencies to cease participation in and funding for 66 international organisations—35 outside the United Nations system and 31 UN entities—following a year-long review mandated by an earlier executive order in February 2025. That review, conducted by the Secretary of State in consultation with the U.S. Representative to the United Nations, examined whether continued U.S. membership, support or funding aligned with national interests. After receiving the findings and consulting his Cabinet, Trump concluded that continued engagement with the listed organisations was no longer in the interest of the United States and instructed agencies to implement the withdrawals as permitted by law, with further reviews continuing.

The directive came days after the administration publicly confirmed a U.S. operation that resulted in the apprehension of Nicolás Maduro and intensified enforcement actions against Venezuela’s oil sector, including the seizure of sanctioned, Russia-registered vessels. Defending the operation, Secretary of State Marco Rubio said U.S. forces were deployed briefly and described the action as part of a broader effort to curb drug trafficking, restrict Iranian and Hezbollah activity in the Western Hemisphere, and prevent sanctioned oil revenues from benefiting U.S. adversaries. The administration has presented both the withdrawals from international bodies and the Venezuela actions as elements of a wider recalibration of U.S. foreign policy under Trump’s second term.

The scope of the decision is unusually broad, cutting across sectors that have long formed the backbone of multilateral cooperation. On the non-UN side, the list ranges from climate- and energy-related bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the International Renewable Energy Agency and the International Solar Alliance, to governance, democracy and rule-of-law institutions, including the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe and the Freedom Online Coalition. It also encompasses specialised forums dealing with migration, biodiversity, mining, cultural preservation, environmental cooperation, counterterrorism, cyber expertise, maritime piracy, regional research networks and scientific and technological cooperation, including in Ukraine.

Equally striking is the withdrawal from 31 UN-linked entities. These include core components of the UN’s economic and social architecture, such as the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, all five regional economic commissions under the UN Economic and Social Council, the Peacebuilding Commission and Peacebuilding Fund, and the UN Conference on Trade and Development. The directive also ends U.S. participation in UN Women, the UN Population Fund, UN Habitat, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, UN Water, UN Oceans and the UN University, as well as offices addressing children in armed conflict and sexual violence. For UN bodies, withdrawal is defined as ceasing participation or funding to the extent permitted by law.

Reacting to the announcement, the United Nations said Secretary-General António Guterres today regretted the U.S. decision to withdraw from a number of UN entities. In a statement issued by his spokesperson, the Secretary-General underscored that assessed contributions to the UN’s regular and peacekeeping budgets, as approved by the General Assembly, constitute a legal obligation under the UN Charter for all Member States, including the United States. The statement added that all UN entities would continue implementing the mandates given to them by Member States, stressing that the organisation has a responsibility to deliver for those who depend on its work and would carry out its responsibilities with determination despite the U.S. decision.

In a fact sheet accompanying the memorandum, the White House argued that continued U.S. participation in many of these organisations no longer delivered commensurate benefits and often advanced agendas that conflicted with U.S. security, economic priorities or sovereignty. It said American taxpayers had spent billions of dollars on institutions that were inefficient, ineffective or openly critical of U.S. policies, and maintained that resources would be better redirected toward domestic priorities such as military readiness, infrastructure and border security. The administration framed the move as restoring sovereignty and reallocating taxpayer funds away from what it described as ineffective or hostile global agendas.

The withdrawals build on earlier decisions taken since Trump returned to office, including renewed exits from the World Health Organization and the Paris Climate Agreement, formal notification to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development that its global tax deal has no force in the United States, and orders ending U.S. participation in the UN Human Rights Council while prohibiting future funding for UNRWA. Taken together, these steps amount to a systematic narrowing of America’s role in multilateral institutions that have shaped global governance since World War II.

At the same time, Trump signed a far-reaching executive order reshaping defence contracting, aimed at what the administration describes as a long-standing imbalance between shareholder returns and military readiness. The order bars underperforming defence contractors from stock buybacks and dividends, empowers the newly renamed Department of War to amend contracts, invoke the Defense Production Act, cap executive compensation and link incentive pay to on-time delivery and production speed. The stated objective is to accelerate procurement, expand production capacity and ensure that the defence industrial base can meet U.S. and allied needs in what the administration characterises as a more dangerous global environment.

These domestic and international decisions intersect with the administration’s handling of Venezuela. Days earlier, Rubio publicly defended the U.S. operation that apprehended Maduro, whom the administration describes as an indicted narcoterrorist and illegitimate former Venezuelan leader. He emphasised that U.S. forces were on the ground only briefly, that the action did not amount to an invasion or extended military engagement, and that it did not require prior congressional approval. Rubio said the operation was conducted in the national interest to curb drug trafficking, expel Iranian and Hezbollah influence, and prevent Venezuela’s oil industry from enriching adversaries. He added that pressure would continue through what he termed an “oil quarantine,” including vessel seizures and restrictions on oil exports, until Washington sees tangible changes.

Taken together, these actions point to a foreign policy that places less emphasis on multilateral rule-making and greater reliance on unilateral leverage, selective partnerships and direct enforcement. The moves have drawn sharply divided reactions in Washington. Supporters argue that withdrawing from sprawling international bureaucracies frees resources, reduces constraints on U.S. policy, restores autonomy and allows the United States to act more decisively in defence of its interests, particularly in the Western Hemisphere, while tougher defence contracting rules and hemispheric enforcement enhance deterrence and readiness.

Critics counter that disengagement from institutions dealing with climate, development, population, trade and peacebuilding risks ceding influence to rival powers, weakening global coordination on transnational challenges and eroding norms the United States helped establish.

For allies and partners, the decisions signal a more selective and transactional U.S. approach to international cooperation. Countries that relied on UN platforms for funding, coordination or diplomatic leverage may need to seek alternatives, while others may adjust to a U.S. strategy that places greater emphasis on bilateral leverage and enforcement. In areas such as climate science and biodiversity, U.S. withdrawal from global bodies could shift leadership and agenda-setting to other major powers.

Inside the United States, the longer-term effects remain uncertain. While the administration emphasises sovereignty and efficiency, the simultaneous pullback from institutions designed to manage global risks and the expansion of unilateral enforcement may place greater demands on U.S. military, legal and economic tools. The defence contracting overhaul acknowledges existing production shortfalls even as it seeks to correct them through stricter oversight and incentives.

The implications for the United States are complex. Financially, ending funding to dozens of bodies could yield short-term savings and simplify budgetary choices. Politically, it reinforces a long-standing “America First” narrative that resonates with voters sceptical of global institutions. Strategically, however, disengagement from forums where standards, data and norms are set may reduce Washington’s ability to shape outcomes indirectly, even as it increases reliance on sanctions, seizures and executive authority.

For the wider world, the signal is equally stark. Allies accustomed to U.S. leadership within multilateral systems must adjust to a partner that is more selective and transactional. Developing countries that relied on UN platforms for funding, coordination or advocacy may face gaps that other powers could fill. In the Western Hemisphere, the Maduro operation underscores that the United States is prepared to act decisively within its perceived sphere of influence, potentially deterring some actors while heightening concerns about precedent and escalation.

Ultimately, Trump’s January 2026 decisions amount to a redefinition of how Washington balances sovereignty, cooperation and power projection. Whether this approach strengthens U.S. influence by concentrating resources and resolve, or weakens it by narrowing the arenas in which America leads, will depend on how allies respond, how rivals adapt, and whether unilateral action can substitute for institutions built to manage an increasingly interconnected world.

– global bihari bureau