Geneva Sounds Alarm on Future of U.S.–Africa Trade

Geneva: Market access to the United States could soon become significantly costlier for many African exporters as the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) approaches its expiry on September 30, 2025. If AGOA lapses, African exporters will face Most-Favoured-Nation (MFN) tariffs under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, eroding the price advantages that have made them competitive.

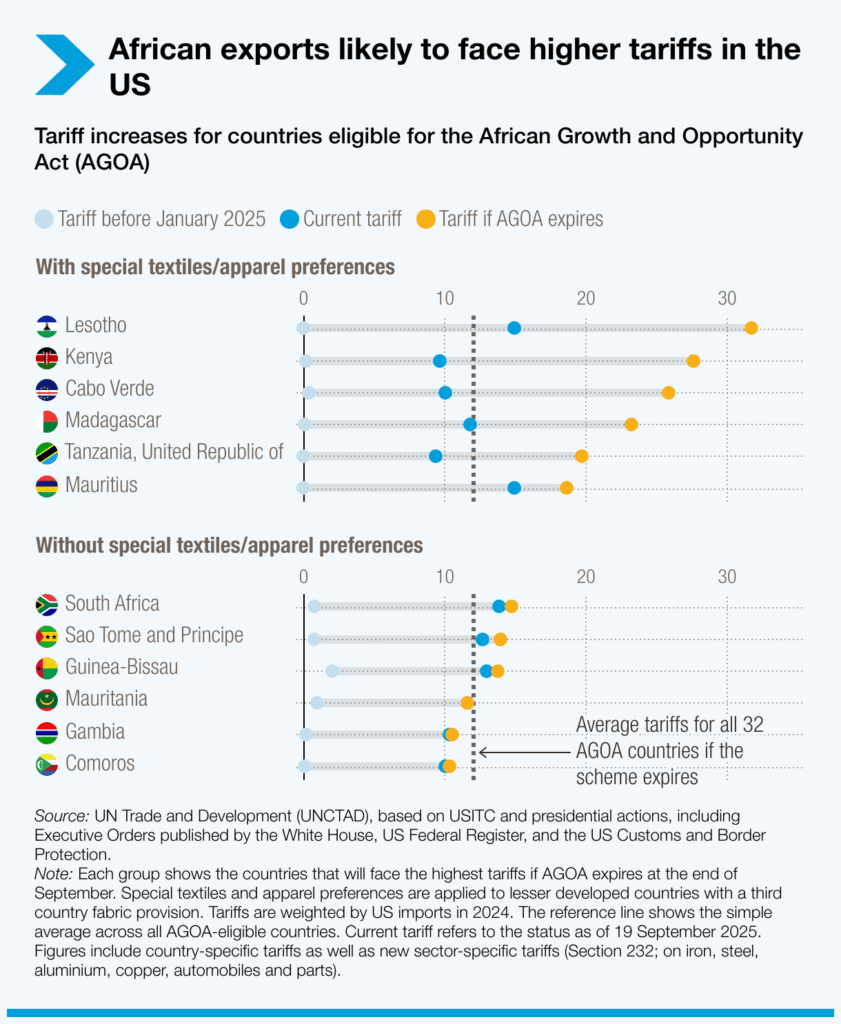

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) analysis highlights that textiles, apparel, and certain agricultural products are particularly vulnerable. For Kenya, the change would be dramatic: its trade-weighted average tariff would jump from roughly 10 per cent under AGOA to nearly 28 per cent without it, threatening apparel exports from hubs such as Athi River and Mombasa. Madagascar, another apparel-driven economy, would see average tariffs nearly double to about 23 per cent, undercutting a sector already competing with low-cost Asian suppliers. Lesotho’s garment industry, one of its largest private-sector employers, faces the risk of factory closures and job losses if U.S. buyers divert orders elsewhere due to higher costs. South Africa, the largest AGOA beneficiary, relies on the programme to keep automotive exports, wine, citrus fruit, and manufactured goods competitive in the U.S. market. Termination of AGOA would raise tariffs on vehicles and auto parts, threatening jobs in its industrial heartland. Ethiopia and Ghana, both of which have apparel industries built partly around AGOA access, could also see thousands of jobs at risk.

Economists warn that such tariff shocks could trigger a retreat of investors and unravel supply chains that took years to establish. UNCTAD reports that the sudden removal of preferential treatment could reduce African export revenues by as much as 15–20 per cent for some sectors.

Introduced in May 2000 as a non-reciprocal trade preference programme (where one side offers trade benefits without requiring equivalent concessions from the other), AGOA grants duty-free access (allowing products to enter the United States without paying import tariffs) for more than 1,800 products from eligible sub-Saharan African economies, including a special window for textiles and apparel benefiting 21 lesser-developed countries as defined by the United States.

In 2023, imports under AGOA reached nearly $10 billion – a small fraction of total U.S. merchandise imports but a lifeline for economies like Lesotho and Madagascar, where entire sectors have been built on preferential access to the American market. According to UNCTAD, AGOA has been instrumental in supporting these exports and sustaining industrial and employment growth in beneficiary countries. The programme has boosted African exporters’ competitiveness, particularly in apparel and manufacturing, and has helped attract United States foreign direct investment (FDI) that created jobs and built more resilient supply chains.

For American companies, AGOA has meant lower prices on fuels, metals, and intermediate goods, strengthening downstream competitiveness. Still, not all countries have harnessed AGOA fully, with many struggling to diversify exports away from primary commodities. Utilisation rates vary widely, leaving some economies more vulnerable than others as the programme’s future hangs in the balance. UNCTAD notes that uneven utilisation remains a challenge for trade policy planners across sub-Saharan Africa.

African leaders have responded with a flurry of diplomatic outreach.

Kenya’s President William Ruto has publicly urged Washington to renew AGOA for at least five years, describing it as “a platform that connects Africa and the U.S. in a very fundamental way, and it can go a long way in solving some of the trade deficits and challenges that exist at the moment.” He stressed that Kenya is seeking broader access for tea, coffee, avocados, and new sectors such as mining and fisheries. The Kenya Private Sector Alliance (KEPSA) has echoed this call, warning that without renewal, jobs and investor confidence will suffer.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa has gone further, using his appearance at a United States–South Africa Trade and Investment Dialogue during the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) to warn that letting AGOA lapse would “seriously damage South Africa’s economy and undermine decades of progress in U.S.–Africa trade.” He pointed out that AGOA has supported employment from auto assembly plants to wine farms and urged Washington to maintain predictable market access, saying that both sides rely on “a trade relationship that is mutually beneficial.” in this context, th U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau met with South Africa Foreign Minister Lamola on the margins of the United Nations General Assembly on September 24, 2025, to discuss topics of mutual interest in the bilateral relationship and identify areas requiring continued dialogue. Ramaphosa today stated in his weekly letter to South Africans that the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition of South Africa has been engaging with US trade representatives to agree to the reciprocal trade agreement designed to benefit both countries.

Lesotho’s Trade and Industry Minister Mokhethi Shelile has personally engaged with U.S. lawmakers, meeting officials from the House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee. According to him, members “all agreed that AGOA has to be extended and they promised us that by November or December … it will be extended by a year.” But he warned that a lapse would risk “losing more jobs,” underscoring that his country’s textile industry is almost entirely AGOA-driven.

The pressure on Washington is therefore coming not only from African governments but also from business associations, exporters, and trade unions that fear the social and economic fallout of higher tariffs. U.S. importers and retailers have also lobbied for renewal, arguing that African sourcing provides diversification benefits and cushions supply-chain risks away from over-reliance on Asia. UNCTAD underscores that the lapse of AGOA would have ripple effects beyond Africa, affecting global supply chains and U.S. importers relying on African raw materials and apparel.

Policy experts warn that time is running short. Negotiating a full renewal or a longer-term successor arrangement could take months, leaving exporters vulnerable to a disruptive gap. In the absence of AGOA, Africa’s efforts to expand manufacturing and climb global value chains could face a severe setback. Some see this as a wake-up call to accelerate implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) to boost intra-African commerce, but acknowledge that such structural changes cannot replace the U.S. market overnight.

For now, AGOA’s future remains in the hands of U.S. lawmakers. The next few days will determine whether 25 years of preferential trade relations are preserved or whether African exporters face a sudden tariff cliff that could reverberate across industries and labour markets from Nairobi to Maseru to Johannesburg. UNCTAD stated today that it continues to monitor the situation closely and has highlighted the urgency of coordinated action to prevent economic disruption.

– global bihari bureau