©FAO/Paola Ortolani

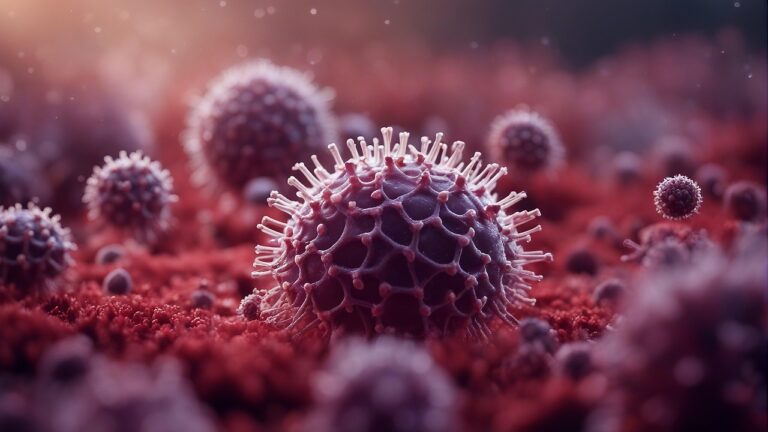

Sea urchins play a critical role in marine biodiversity, and their survival is intertwined with the health of the seas. The population of sea urchins in the Mediterranean region has garnered attention. While the species’ status and impacts can differ based on local factors and harvesting practices, conservation efforts are required in certain areas.

As one of the organisms that defines the ecological system in the region, it has also been used as a model in developmental biology and as a means for assessing environmental quality. Sea urchins are sensitive to environmental conditions, and this species has been affected by climate change and pollution. The sea urchin is also considered a culinary delicacy in many countries and faces the additional threat of overfishing in some areas.

However, while some sites are lacking in the species, other areas are experiencing excessive sea urchin populations that can lead to the depletion of algae and other marine vegetation, so-called sea urchin barrens. These two contrasting situations call for individualized solutions.

In the azure waters surrounding the Italian island of Procida in the Gulf of Naples lies a rich and dynamic marine environment. This is the home of the stony, purple sea urchin (Paracentrotus lividus), an important herbivore, as well as prey for a number of fish, starfish and molluscs. This small and spiky creature regulates the volume of algae and is therefore a key species in keeping intact the dynamics of ecosystems close to the seashore.

In Procida, where sea urchins face overfishing, the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) engaged with local producers and researchers to perform underwater sampling, collecting valuable information on sea urchin farming and restocking. This is helping to boost farming of sea urchins, valued for its prized roe while providing vital scientific guidance for restoring local sea urchin populations.

The GFCM is helping countries and farmers on one hand, by creating specific guidelines for restorative aquaculture, concentrating on key species like sea urchins, algae and shellfish, and on the other, by helping with the removal of urchins and their sale in culinary markets, helping to restore algae populations while enhancing the value of these species.

The GFCM conducted a series of technical consultations with Echinoidea, a small-scale aquaculture facility which was established in Procida in 2016. Echinoidea, in collaboration with the research institute, Anton Dohrn Zoology Centre (Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn), has produced more than 20,000 sea urchin larvae through artificial fertilization at the Procida farm. Once the adults are ready, they are released back into their natural environment to continue growing in an area specifically intended for aquaculture, helping to alleviate the pressures of sea urchin fishing of wild populations.

The GFCM’s Maissa Gharbi says, “Sea urchin aquaculture is a very promising field, yet it is challenging due to the very high mortality rates recorded during early stages of life. Production of sea urchins requires extensive monitoring and attention during the reproduction process.”

Although the Procida initiative still requires further development, it has the potential to become a model for sea urchin farming that could be expanded across the Mediterranean Sea.

“Sea urchin farming is a new activity that combines innovation with the restoration of ecosystems. It must be studied well so that the right models can be proposed for the Mediterranean and Black Sea region,” says Ibrahim Al Hawi, Chairperson of the GFCM Scientific Advisory Committee on Aquaculture.

“Restorative aquaculture leads to improved environmental sustainability and ecosystem services alongside supplying aquatic foods and opportunities for livelihoods,” says Al Hawi.

The GFCM recently produced a booklet with guidelines for sustainable replenishment and called for more intense monitoring of vulnerable species, including sea urchins.

“The main purpose of these guidelines is to support Mediterranean and Black Sea countries in restocking and stock enhancement while preventing harm to biodiversity, natural habitats, ecosystems and related ecosystem services, based on good practices and the best available knowledge,” says Al Hawi.

Restoring balance

In a separate project in Spain, the GFCM is collaborating with Urchinomics, the Department of Climate Action, Food and Rural Agenda (DACC) in Catalonia and the Institute of Agrifood Research and Technology (IRTA), on the restoration of macroalgal forests and seagrass meadows. Sea urchins overgraze these types of marine vegetation. With an overpopulation of sea urchins, which can be caused by organic pollution, overfishing of their predators and phytoplankton productivity, some of these areas have become barren, putting stress on the ecosystem and other species that depend on algae. The GFCM has supported their removal, so that seaweed and seagrasses may regrow. These sea urchins are then sold in markets that value them for their roe.

Mediterranean-wide practices

The GFCM is also working with DACC to develop the Mediterranean Restorative Aquaculture Centre, a unique site for subregional innovation and capacity building for countries from the western Mediterranean.

The Centre aims to develop knowledge and capacities for restorative aquaculture (including that of sea urchins), promote innovation and share best practices, such as the research and restocking activities of the Procida pilot project.

Through the GFCM, FAO said it is committed to supporting their role in nature while securing their commercial viability for the sake of fishing livelihoods.

Source: the FAO News and Media office, Rome

– global bihari bureau