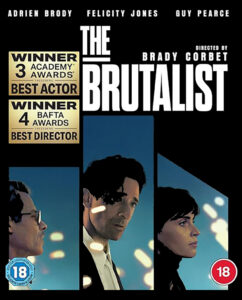

Film Review: The Brutalist (2024)

Director And Producer: Brady Corbet

Brady Corbet’s multiple Oscar-winning epic is exquisitely constructed, but ultimately empty. The Brutalist arrives with all the solemnity of a memorial unveiling. Shot in resplendent VistaVision, running close to four hours, and adorned with a level of period detail that borders on obsessive, it is a film that invites admiration. And yet, by the end of its meticulously composed journey, what remains is less an emotional impact than a kind of intellectual fatigue. For all its visual splendour, The Brutalist is a curiously vacant experience.

Brady Corbet’s multiple Oscar-winning epic is exquisitely constructed, but ultimately empty. The Brutalist arrives with all the solemnity of a memorial unveiling. Shot in resplendent VistaVision, running close to four hours, and adorned with a level of period detail that borders on obsessive, it is a film that invites admiration. And yet, by the end of its meticulously composed journey, what remains is less an emotional impact than a kind of intellectual fatigue. For all its visual splendour, The Brutalist is a curiously vacant experience.

The story centres on László Tóth (Adrien Brody), a Jewish-Hungarian architect and Holocaust survivor who migrates to post-war America in search of renewal. It is, on paper, a deeply resonant premise. But Corbet treats Tóth less as a man than a symbol—stoic, silent, emotionally impenetrable.

Brody, talented though he is, plays Tóth with a mannered detachment: the squint, the cigarette, the clenched jaw—all hallmarks of a tired cliché that’s bound to please his fanbase, just as Clint Eastwood’s nameless cowboy, with his ever-present spiff and impassive stare in movie after movie, once thrilled fans of the spaghetti western. It’s a performance rooted more in repetition than revelation, one that suggests gravity without uncovering anything new beneath the surface.

That same sense of studied artificiality permeates the film. There is clearly no shortage of care here: actors underwent extensive language coaching in Hungarian; AI was employed to refine accents to a degree that might impress native speakers. The art direction is exquisite, the costumes peerlessly curated, and the architecture—well, the architecture is practically the co-star. Yet what becomes increasingly clear is that this is a film built from the outside in. For all its polish, it lacks a beating heart.

But unlike filmmakers wrestling with period material and backed by a handsome budget—say, Coppola, who in The Godfather used surface detail in service of a scathing, coherent critique of American capitalism—Corbet offers no such unifying thesis. The Brutalist flirts with weighty themes: displacement, memory, and cultural erasure. But only at the level of what’s already common knowledge, and with a banality that borders on the predictable. The familiar Horatio Alger blueprint has been done to death, and here it returns without irony or reinvention. The narrative lurches forward, sometimes aimlessly, sometimes grandiosely, but never with purpose.

By the end, the film’s most laboured aspects—its costuming, its design flourishes, its fetishistic attention to detail—feel not only hollow for their failure to serve any deeper intellectual or emotional idea, but occasionally verge on the vulgar. It plays like a lavish counterpoint to the miserly budgets of neorealist masters—De Sica, Satyajit Ray, Rossellini—whose cinema, stripped of ornament, delivered profound human insight. The Brutalist, by contrast, is too distracted by its own surfaces to reach anything close.

A central weakness lies in the film’s failure to interrogate its own setting. Tóth’s escape from institutionalised anti-Semitism in Europe lands him in a post-war America still mired in its own forms of bigotry. But the film refuses to engage with this tension. There is no reflection on the racial violence of the time, no juxtaposition between the traumas of Europe and those endured by African Americans, Native Americans, or other marginalised groups in the US. What could have been a trenchant exploration of prejudice’s new shapes is instead rendered in abstraction, as if Corbet feared muddying the film’s visual purity with real-world mess.

Even small choices feel oddly regressive. Immigrants speak stilted English among themselves, as if to reassure the Hollywood ear. After all, Nazi characters have been conversing among themselves in perfect English—with the usual theatrical Teutonic inflection—for generations in Hollywood films. One need only recall Dances with Wolves to see how authentic use of language can humanise rather than flatten. The Brutalist seems content to rehearse old tropes in a new frame.

And what of the audience response? Perhaps most dispiriting is the critical reverence the film has received—its awards haul, its box office success, its place on AFI’s top ten list. Something is disquieting about the eagerness with which viewers have embraced this hollow monument, as though beauty and solemnity alone constitute substance. It recalls the critical gymnastics that so often accompany blockbuster franchises that dominate global cinema, such as the rebooted Spider-Man films, where a throwaway line like “With great power comes great responsibility” was elevated to the level of geopolitical commentary. What began as a simple line from a man in Lycra became, in the hands of overreaching critics, a supposed profound critique of Bush-era foreign policy. The same contortions are now applied to The Brutalist, a film whose gravity is largely projected onto it rather than earned from within.

(Streaming on JioCinema / JioHotstar and available to rent on Amazon Prime, ZEE5 and Hungama Play)