India’s 2.7M TB Cases Fuel Global Fight

Geneva: Tuberculosis (TB) incidence in India drops by 21% from 237 per lakh population in 2015 to 187 per lakh population in 2024 – almost double the rate of decline observed globally. India has achieved a higher reduction in mortality due to TB than the global reduction (TB deaths in HIV negative people). Treatment coverage increases to 92%, placing India ahead of other high-burden countries and global universal health coverage (UHC).

Geneva: Tuberculosis (TB) incidence in India drops by 21% from 237 per lakh population in 2015 to 187 per lakh population in 2024 – almost double the rate of decline observed globally. India has achieved a higher reduction in mortality due to TB than the global reduction (TB deaths in HIV negative people). Treatment coverage increases to 92%, placing India ahead of other high-burden countries and global universal health coverage (UHC).

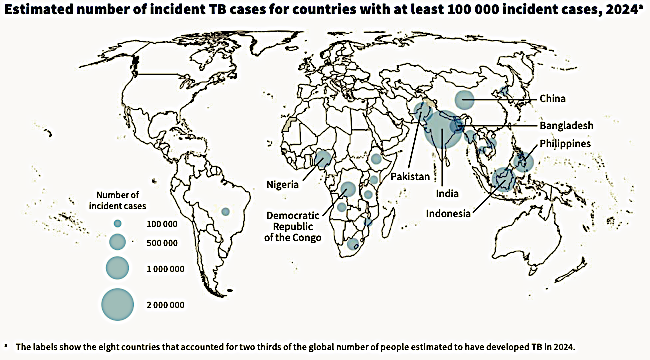

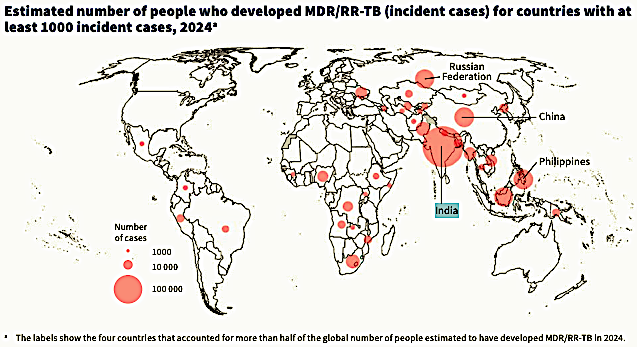

Still, India carries one-fourth of the world’s TB burden: 2.7 million new cases in 2024, 25% of the global total of 10.7 million. Incidence fell 2.5% year-on-year, mortality 3.2%, yet over 900,000 cases went undetected—only 67% notified. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB) hit 140,000, 32% of the world’s total; detection reached 58%, treatment success 71%. Among HIV-negative deaths, India accounted for 28%. Undernutrition affected 40% of patients, HIV co-infection 5%; social protection covered just 19%.

India’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare claimed today that innovative case finding approach, driven by the swift uptake of newer technologies, decentralization of services and large scale community mobilization, has led to the country’s treatment coverage to surge to over 92% in 2024, from 53% in 2015 – with 26.18 lakh TB patients being diagnosed in 2024, out of an estimated incidence of 27 lakh cases. “This has helped reduce the number of ‘missing cases’ – those who had TB but were not reported to the programme – from an estimated 15 lakhs in 2015 to less than one lakh in 2024,” it pointed out.

Yet, in 2024, the global gap between estimated TB incidence and the reported number of people newly diagnosed with TB was mostly accounted for by 10 countries (Fig. 21). These 10 countries collectively accounted for 63% of the global gap. The top five countries (collectively accounting for 40% of the global gap) were Indonesia (10%), India (8.8%), the Philippines (7.5%), Pakistan (7.2%) and China (6.9%). From a global perspective, efforts to increase levels of case detection and treatment are of particular importance in these countries.

These figures form the core of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Tuberculosis Report 2025, released November 12, 2025. Worldwide, 1.2 million people died from TB—still the top infectious killer. Incidence declined 2%, mortality 3%; 8.3 million received treatment, and rapid tests reached 54% of suspects. Funding, however, stood at $5.9 billion—only 27% of the $22 billion annual target needed to end TB by 2030. Research funding in 2023 was $1.2 billion, 24% of requirements. Projected donor cuts from 2025 could add 2 million deaths and 10 million cases by 2035.

This concentration of disease persists: 87% of cases in 30 high-burden countries, led by India at 25%, and followed by Indonesia at 10%, the Philippines at 6.8%, China at 6.5%, Pakistan at 6.3%, Nigeria at 4.8%, Democratic Republic of Congo at 3.9%, and Bangladesh at 3.6%. Since 2015, Africa has cut incidence by 28% and deaths by 46%; Europe achieved 39% and 49%. More than 100 countries reduced incidence by 20%, and 65 lowered deaths by 35% or more. Treatment success for drug-susceptible TB reached 88%; for resistant forms, 71%, with 164,000 lives lost. Preventive treatment covered 5.3 million people. Since 2000, care has saved 83 million lives.

Among the 30 high TB burden countries in 2024, the number of people newly diagnosed with TB and officially reported as a TB case as a percentage of the estimated number of people who developed TB (incident cases) was highest (>80%) in Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Mozambique, Uganda and Zambia.

Yet funding has remained flat since 2020. Social protection varies widely—from 94% coverage in Mongolia to 3.1% in Uganda—with 19 high-burden countries below 50%. Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warns: “Progress is not victory. TB claiming over a million lives yearly is unconscionable.” Dr Tereza Kasaeva adds: “We are at a defining moment. Funding cuts threaten gains, but commitment can end this killer.” The innovation pipeline includes 63 diagnostics, 29 drugs, and 18 vaccines—six in Phase 3. The 2023 UN pledges remain largely unmet.

Building on these challenges, the End TB Strategy—adopted in 2014 by the World Health Assembly—aims for a 90% reduction in incidence and 95% in mortality by 2035 from 2015 levels. The 2025 milestones of a 35% incidence drop and 75% mortality decline were missed globally. Its three pillars—patient-centred care, supportive policies, and intensified research—continue to guide the response.

The 2023 UN High-Level Meeting reinforced this framework, pledging $22 billion annually for implementation by 2027 and $5 billion for research. Global models show that full funding could prevent 40 million deaths by 2035, while the current path risks 23 million.

Underpinning these projections is stronger data. In 2024, 192 countries submitted surveillance reports. Prevalence surveys in 17 countries since 2015 sharpened estimates. Bayesian modelling integrated vital registration, now covering 70% of deaths in high-burden areas. Historical revisions increased cumulative deaths from 2000 to 2023 by 2 million.

The high-burden country lists for 2025–2029 retain 30 nations, plus three focused on TB/HIV and MDR-TB. The TB-SDG monitoring framework tracks 14 indicators across impact, service delivery, and social determinants.

Of the 30 high MDR/RR-TB burden countries, 24 reached a coverage of at least 80% in 2024: Angola, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Belarus, China, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Peru, the Republic of Moldova, the Russian Federation, Somalia, South Africa, Tajikistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Viet Nam, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Five countries accounted for about 60% of the gap between the estimated global number of people who developed MDR/RR-TB in 2024 (incident cases of MDR/ RR-TB) and the global number of people enrolled on treatment in 2024. Listed in order of their share of the global gap, these countries were India (33%), the Philippines (9.3%), Indonesia (7.3%), China (6.1%) and Pakistan (4.1%).

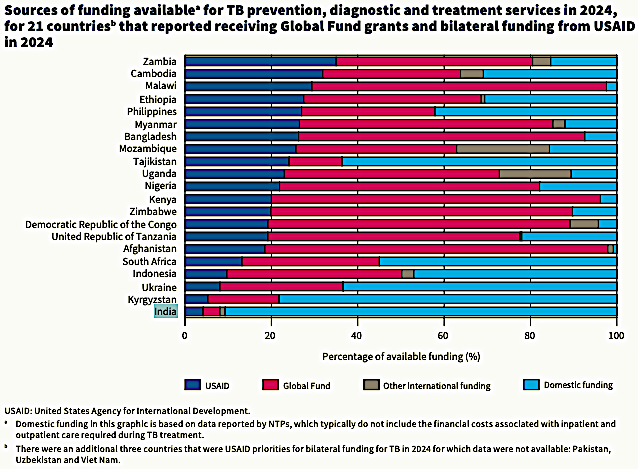

Throughout the period 2015–2024, the share of funding available from domestic and international sources in low – and middle-income countries (LMICs) was relatively consistent. In 2024, 82% of the funding available for TB prevention, diagnostic and treatment services was from domestic sources. International donor funding amounted to US$1.1 billion in 2024, having ranged from US$1.1 billion to US$1.2 billion in almost every year since 2015,3, with most of this funding provided through grants from the Global Fund and bilateral funding from USAID. In 2024, the overall figure for the share of funding provided from domestic sources in LMICs continued to be strongly influenced by the five original BRICS countries: Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China and South Africa. Together, these countries accounted for US$3.1 billion (64%) of the total of US$ 4.8 billion in 2024 that was provided from domestic sources.

In 2024, government of the United States of America (USG) bilateral funding accounted for 20% or more of the total available funding reported by NTPs in 13 of the USG priority countries for TB, with the highest share (over 30%) in Zambia and Cambodia (Fig. 29). Almost all the countries that received USG bilateral funds for TB in 2024 were also highly reliant on Global Fund grants in 2024 (the main exception was India).

National values for the percentage of the population facing catastrophic out-of-pocket expenditures on health are available for different years, and there is more geographical variability than with the service coverage index (SCI), including within regions. Of the 30 high TB burden countries, estimates of the percentage of the population facing catastrophic health expenditures are particularly high (≥15% of the population) for Angola, Bangladesh, China, India, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Uganda. Values for both indicators in the 30 high TB burden countries show that there is a long way to go before the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets for Universal Health Coverage (UHC) are achieved in most of these countries. Only Thailand stands out as having a very high SCI (82 in 2021) and a low level of catastrophic out-of-pocket health expenditures (2.0% of households).

Between 2000 and 2022, there were striking increases in health expenditure (from all sources) per capita in a small number of high TB burden countries, notably the upper-middle-income countries of Brazil, China, South Africa and Thailand. There have also been considerable increases in several lower-middle-income countries: Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Lesotho, Mongolia, Myanmar, the Philippines and Viet Nam. Health expenditure has been rising in most low-income and high TB burden countries, most noticeably in the Central African Republic, Ethiopia, Liberia and Mozambique, albeit from much lower levels.

To achieve UHC, substantial increases in investment in health care are critical. Economic hardship remains a barrier: catastrophic costs exceeding 20% of household income affect half of all TB patients, down from 66% in 2015. Integrating TB into universal health coverage could prevent 1.5 million cases each year.

On the diagnostic front, WHO-endorsed rapid molecular tests now cover 54% of initial evaluations, up from 41% in 2020. AI-supported chest X-rays, piloted in 12 countries, achieved 90% sensitivity. Shorter regimens like BPaL cure 89% of MDR-TB cases in nine months. Preventive treatment with rifapentine-isoniazid, used in 40 countries, reduces duration to three months.

Research funding prioritises drugs (60%), vaccines (20%), and diagnostics (15%), with basic science receiving under 5%. The TB Vaccine Accelerator Council supports trials for candidates such as M72/AS01E and BCG revaccination.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus writes in the foreword: “This is a crucial period. Even as we must strive to meet the commitments from the second United Nations high-level meeting on TB, we have entered a new period of scarcity. WHO is committed to working with donors, partners and affected countries to mitigate the impact of funding cuts, find innovative solutions, and mobilise the political and financial commitments needed to End TB.”

Dr Tereza Kasaeva concludes: “We are at a defining moment in the fight against TB. Funding cuts and persistent drivers of the epidemic threaten to undo hard-won gains, but with political commitment, sustained investment, and global solidarity, we can turn the tide and end this ancient killer once and for all.”

– global bihari bureau