Smart Choices Need Social Research for India’s Rise

If Viksit Bharat (Developed India) is our North Star, we must invest not only in highways and hydrogen, but also in how we make choices. None of this is guesswork. It is research, deliberation and democratic accountability – exactly what social science at its best enables. Without this backbone, we risk building roads without knowing where people are going, or hydrogen hubs without knowing who gets left out.

The world is in flux. Supply-chain realignments, technological decoupling, climate shocks, fragile labour markets, and information disorder have raised the premium on anticipatory governance.

In such an environment, governments that invest in social knowledge – on behaviour, institutions, incentives and norms- are better equipped to choose wisely: what to tax and subsidise, whom to target and protect, which externalities to price, which trade-offs to own. If India is serious about becoming ‘Viksit Bharat‘ by 2047, it must make a far stronger business case—and budgetary commitment—for social science research (SSR). The gains are not intermittent “soft” benefits; they are foundational: better programme design, sharper delivery, lower leakage, more inclusive growth, and ultimately, a sturdier democracy.

What do we know about the state of SSR in India?

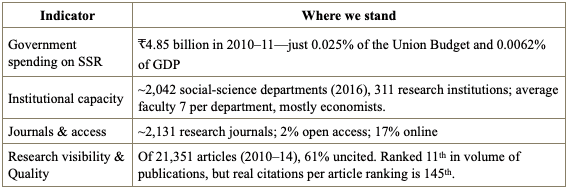

The table below mentions a few telling indicators, drawn from the first comprehensive, empirical exercise undertaken by the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR) on the state of social science research and policy in India since independence- published by Oxford University Press in 2017- which this author had the honour of co-editing. This study was a result of collaboration among 31 senior researchers, drawn from ICSSR institutes across 8 states and was guided by the National Advisory Panel of 12 eminent social scientists. This was a truly multi-disciplinary exercise; the researchers were drawn from more than 10 disciplines.

What the numbers say (at a glance)

To be sure, some of the above indicators are a reflection of the structural asymmetries in global knowledge production (biases in international journal publications, language, peer-review limitations, etc). Nonetheless, there is little gainsaying that these numbers are not mere statistics; they are signposts to where policy capacity falters. Under-investment, thin faculty benches, limited open access and uneven visibility depress the returns India can harvest from research. Yet the same evidence also shows SSR does reach policy- just not often enough. Across ministries and plan documents, hundreds of scholarly references underpin design choices; the bottleneck is translation and discoverability, not relevance. It is also noteworthy that social scientists’ self-reported quality of SSR is ‘low-to-moderate’, and its policy impact is ‘poor-to-moderate’.

A turning point: ANRF and ICSSR signal intent

The last two years mark a welcome inflection. The Anusandhan National Research Foundation (ANRF) is operationalising a whole-of-system approach to research under the NEP’s vision, with a clear emphasis on the “ease of doing research” and on building talent pipelines. Consider just three examples that show the direction of travel: the Convergence Research Centres of Excellence, the Prime Minister’s Early Career Research Grant, and the PAIR—Partnerships for Accelerated Innovation and Research programme that pairs emerging universities with top-tier hubs in a mentorship model. Together, these initiatives create on-ramps for early-career scholars, promote multi-institutional collaboration, and nudge research towards complex societal challenges where social science is indispensable.

On the social-science side of the house, ICSSR has widened its aperture with moves that directly strengthen the evidence spine for public policy- for instance, Longitudinal Studies in Social and Human Sciences (2nd call, 2025) and a special multi-disciplinary call focused on Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups. These are precisely the sort of long-horizon datasets and sector-specific inquiries that governments and philanthropies can use to improve design and targeting.

These steps deserve recognition. They reflect a clear and growing commitment by the Government of India and its apex research bodies to treat knowledge as public infrastructure: build talent, build platforms, build partnerships. But they must now be scaled, coordinated and sustained- because the urgency is real.

The business case: The 3Cs

Cost. SSR is inexpensive relative to its upside. Doubling public SSR allocations over five years would cost a rounding error in the Union Budget but could unlock compounding gains across ministries via fewer design errors, faster course corrections, and smarter targeting.

Capability. Evidence capacity is state capacity. Funding people and platforms- doctoral/post-doctoral streams, methods labs, replication funds, and a national open-access SSR portal—directly addresses the bottlenecks Indian scholars report: methodological depth, discoverability and translation. ANRF’s Convergence CoEs, the PM-ECRG pipeline, and ICSSR’s longitudinal work can form the spine of this capability if scaled and synchronised. ANRF’s Prime Minister Professorship Programme is an excellent initiative to harness existing SSR capability in India to raise the national standards of creating and using evidence for the public good.

Confidence. Democracies run on trust. Transparent commissioning, open data and independent peer review increase public confidence in policy trade-offs- essential as the state balances growth, equity and sustainability amid fiscal and social constraints.

Five practical accelerators (for government and philanthropy)

Adopt a National Social Science Research Policy with a 10-year horizon to de-concentrate capacity (new centres in under-served states; performance-linked grants to state universities) and to institutionalise policy labs within ministries.

Create a National SSR Commons—a digital public infrastructure for data, code, journals and preprints (with translation to Indian languages), seeded by government and matched by philanthropy. This solves discoverability and reuse at scale. Some laudable efforts have been made, but much more needs to be done.

Back methodological excellence through competitive “Methods Challenge Grants” and multi-disciplinary clusters (AI & Society; Climate & Livelihoods; Urban Governance & Public Finance) pairing universities, think tanks and state departments and policy makers.

Globalise Indian SSR by funding South–South collaborations, visiting scholar programmes and co-authorship incentives; international partnerships reliably improve quality and visibility. Dakshin is a great initiative but needs greater energetic push.

Mainstream evidence-use in ministries: require short evidence notes for major schemes; fund quick-turn synthesis units; and embed “evidence fellow” cadres within departments so that research routinely informs design, procurement and monitoring.

The 2047 lens

It is the time to strengthen the evidence base for those who fund, govern and reform Indian social science. The good news is that the groundwork has begun: ANRF’s convergence vision and early-career pipeline, and ICSSR’s long-horizon and inclusion-focused calls, are concrete steps forward (with flagship examples like PAIR already seeding hub-and-spoke networks on campuses). The task now is to scale and sustain them—so that India’s researchers can do what the moment demands: build the social technologies that make growth inclusive, resilient and just.

*Economist, public policy professional and an institution-builder, with nearly three decades of experience in international development, grant management and philanthropic leadership.